When the first Atlantic cable was finally laid between Ireland and Newfoundland in August 1858, the Newfoundland terminus building of the Atlantic Telegraph Company was on a site cleared from the forest near the settlement of Bay Bulls Arm in Trinity Bay. Shortly after this, a second building was erected nearby for the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company.

The location of the cable station is variously referred to as Bay Bulls Arm, Bay of Bulls Arm, Bay of Bull’s Arm, Bull’s Arm Bay, or Bull Arm, depending on the writer. The place name was officially changed to Sunnyside in 1930. The Wikipedia entry for Sunnyside has this note: “As the area was first settled, it was known as Bottom of Bay Bulls Arm. The area was known as Bay Bulls Arm for some time and then changed to Bull Arm.”

Because of the early failure of the 1858 cable, the buildings at Bay Bulls Arm were in service for less than a year, so despite the historic significance of the achievement there is little information on the station, and only the ruins of the foundations remain today.

In a document written in 1914 and based on his earlier personal papers and notes, James Patrick Howley, a geologist and surveyor for the Newfoundland government, gave this description of a visit he made to the site in 1869, by which time the structures were gone. He approached from the west:

The distance across this narrowest part of the Isthmus of Avalon between Come-by-Chance in Placentia Bay and Bay Bulls Arm in Trinity Bay is scarcely three miles, and there is quite a well-beaten path over this neck. I travelled this route alone and arrived at the head of the Arm. Here I saw the ruins, or rather the remains, of the Cable buildings which were erected here when the first Atlantic Cable was laid in 1856 [actually 1858]. Everyone knows the history of this Cable, how after a few brief messages between Queen Victoria and the President of the United States, it ceased to work and now lies abandoned at the bottom of the ocean. Old man Adams purchased the buildings and had them drawn across the neck in winter, and converted into hay barns, stables and other out houses.

[From James Patrick Howley: Reminiscences of Forty-two Years of Exploration in and about Newfoundland, page 126. Courtesy of Centre for Newfoundland Studies Archives, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland.]

This map shows the location of Bay Bulls Arm and also that of Heart’s Content, the landing point of the 1866 Atlantic cable, where the former cable station is now a museum.

An undated note on the Town of Sunnyside website [archive copy] gives more information on the fate of the 1858 structures:

Eventually, the Sunnyside cable office was sold to Capt. William Stevenson, who moved it to Harbour Grace and used it as a family home. The building is still standing and was used by the Stevenson family until a few years ago. The outbuildings were sold to the Adams family in Come By Chance.

The Town of Sunnyside has posted a 2009 photograph of the building in Harbour Grace, and it does appear to be one of the station buildings from Bay Bull Arm—the office of the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company, which was immediately adjacent to the Atlantic Telegraph Company’s quarters.

The station building can be seen in the paintings by Linde and Dudley near the end of this page. Here is a detail from Linde’s watercolour for comparison with the Flickr photograph and street view.

Perhaps the best description of the cable station and its surroundings is in the passages below, which are taken from John Mullaly’s 1858 book on the Atlantic cable. Its full title, which leaves no doubt as to the subject matter, is “The Laying of the Cable, Or the Ocean Telegraph; Being a Complete and Authentic Narrative of the Attempt to Lay the Cable Across the Entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1855, and of the Three Atlantic Telegraph Expeditions of 1857 and 1858: with a Detailed Account of the Mechanical and Scientific Part of the Work, as Well as Biographical Sketches of Messrs. Cyrus W. Field, William E. Everett, and Other Prominent Persons Connected with the Enterprise. Illustrated with Portraits, Engravings of the Machinery, and Scenes in the Progress of the Great Work.”

Notes:

The page numbers and links below are to the corresponding sections in Mullaly’s book. The monochrome images are from various issues of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper published in September 1858. The colour illustrations are contemporaneous, but have never before been published. These include four watercolours of the cable station by Theodor Linde, who was a telegraph operator in Newfoundland at the time, and a plan of the site by C.V. de Sauty. The originals were owned by Charles V. de Sauty, a key figure in the 19th century cable industry, and then his son Alfred de Sauty, and have only recently come from the Bill Holly collection to the Atlantic Cable website archive.

See the end of this page for short biographies of C.V. de Sauty, Alfred de Sauty, and Theodor Linde.

At the time of the landing of the cable at Bay Bulls Arm on August 5th 1858, the station was evidently neither completed nor well stocked with supplies and provisions. The extracts from Cyrus Field’s diary shown below (as quoted by Mullaly) reveal the situation.

T.H. Brooking was a director of the Atlantic Telegraph Company, and had lived in Newfoundland for many years. It appears that his firm was the source of finance for the cable company in Newfoundland. C.V. de Sauty supervised the electrical staff on board Niagara, and was Superintendent of the Atlantic Telegraph Company’s operations in Newfoundland.

The Landing of the 1858 Atlantic Cable

Mullaly Page 308:

Friday, August 6, at 2 A.M., steam-tug Blue Jacket arrived from St. Johns, and Mr. Brooking’s partner was one of the passengers. M. De Sauty and myself urged him to have the Telegraph House finished as soon as possible. M. De Sauty purchased supplies from the Niagara, as they had hardly any provisions at the house, and the purser said they could have what they wanted at cost.

Mullaly Page 279:

Mr. Field Makes the First Announcement to the New World that the Cable is Laid.

About eight o’clock on the evening of the 4th instant [August 4th 1858], while the Niagara was proceeding up Trinity Bay, and some seventeen or eighteen miles distant from the landing place, Mr. Field left the ship for the purpose of visiting the telegraph station, and if possible, of sending a despatch to the United States announcing the success of the enterprise. As the boat of the Porcupine was alongside, it was cheerfully placed at his disposal by Captain Otter, who had now undertaken to pilot the Niagara. Mr Field immediately set out, and as the Gorgon was on her way to the Bay of Bulls Arm, at the head of which the cable was to be landed, he went on board that vessel, and his boat was taken in tow. Here he was warmly received by Captain Dayman and his officers, who were in the full enjoyment of success.

It was near two o’clock in the morning before he arrived at the beach, and as it was quite dark, he had considerable difficulty in finding the path that led up to the station. There was no house in sight, and the whole scene was as dreary and as desolate as a wilderness at night could be. A silence as of the grave reigned over every thing before him; while behind, at the distance of a mile, he could see the huge hull of the Niagara looming up indistinctly through the gloom of night, and the light of the lamps on her deck making the darkness still darker and blacker by the contrast. He entered the narrow road, and after a journey of what appeared to be twenty miles came in sight of the station, which stands about half a mile from the beach. There was, however, no sign of life there, and the house, in its stillness, seemed strangely in unison with every thing around. It had a deserted appearance, as if it had long since ceased to be the habitation of man.

In vain he looked for a door in the front, there was no entrance there; he looked up at the windows in the hope, perhaps, of being able to enter by that way, but the windows of the lower story were beyond his reach, and the house having been partly built on piles gave it the appearance of being raised on stilts. A detour of the establishment, however, led to the discovery of a door in the side, and through this he finally succeeded in effecting an entrance. The noise he made in getting in, it was natural to expect, would arouse the inmates, but there seemed to be either no inmates to arouse, or those inmates were not easily disturbed. He stopped for a moment to listen, and as he listened he heard the breathing of sleepers in an apartment near him. The door was immediately thrown open, and in a few seconds the sleepers were awake, wide awake, and opening their eyes wider and wider as the wonderful news fell upon their astonished and delighted ears. They could hardly believe the evidence of their senses, and were bewildered at what they heard. The cable laid! when but a few short weeks before they had received the news of disaster and defeat, and they had looked only to the far distant future for the accomplishment of the great work. The cable laid, and they unconscious of it—they who had waited and watched so many weary days and weeks for the ships they had begun to believe would never come. What! and they were now in the bay—those same ships—within a mile of them! can they be dreaming? Dreaming! no—what they have heard is true, all true, and there is the living witness before them.

“What do you want?” was the exclamation of the first who was awakened, as he endeavored to rub the sleep out of his eyes.

“I want you to get up,” said Mr. Field, “ and help us to take the cable ashore.”

“To take the cable ashore!” re-echoed the others, who were now just awaking, and who heard the words with a dim, dreamy idea of their meaning—”To take the cable ashore.”

“Yes,” said Mr. Field, “and we want you at once.”

They were now thoroughly aroused, and directing Mr. Field to the bedrooms of the other sleepers—for there were four or five others in the house—they prepared themselves with all haste to assist in landing the cable. But the other inmates were already awake, and when Mr. Field made his appearance on the corridor which divides the sleeping apartments on each side of the house, he found them awaiting him in the lightest description of summer clothing. As they had neither pants, vests, coats, shoes nor stockings on, the curious will have no difficulty in discovering in what they were dressed. They were as amazed at seeing Mr. Field as if he were an apparition; and when they recovered themselves sufficiently to ask the meaning of such a strange visitation, they were thrown into another state of wonderment by what he related. When they learned all, they dressed, and prepared themselves for the work before them.

Mr. Field found that the telegraph office would not be open till nine o’clock that morning, and that the operator of the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph was absent at the time. He also ascertained that the nearest station at which he could find an operator was fifteen miles distant, and that the only way of getting there was on foot. Now, fifteen miles in Newfoundland is about equal to twice the distance in a civilized country, and is a tolerably long walk; but it was something to be the bearer of such news to a whole continent, and so two of the young men willingly volunteered for the journey, bearing with them, for transmission to New York and the whole United States, the following despatch, which contained the first announcement of the successful accomplishment of the work, and the historical importance of which will justify its republication here:

UNITED STATES STEAM FRIGATE NIAGARA,

TRINITY Bay, Newfoundland, August 8, 1858.

To THE ASSOCIATED PRESS, NEW YORK:—

The Atlantic Telegraph fleet sailed from Queenstown, Ireland, Saturday, July 17, met in mid-ocean, Wednesday, the 28th, made the splice at one p.m. Thursday, the 29th, and separated. The Agamemnon and Valorous bound to Valentia, Ireland, the Niagara and Gorgon for this place, where they arrived yesterday, and this morning the end of the cable will be landed. It is 1,696 nautical, or 1,950 statute miles from the telegraph house at the head of Valentia harbor to the telegraph house at the Bay of Bull’s Arm, Trinity Bay, and for more than two-thirds of this distance the water is over two miles in depth.

The cable has been paid out from the Agamemnon at about the same speed as from the Niagara.

The electrical signals sent and received through the whole cable are perfect.

The machinery for paying out the cable worked in the most satisfactory manner, and was not stopped for a single moment from the time the splice was made till we arrived here.

Captain Hudson, Messrs. Everett and Woodhouse, the engineers, the electricians, officers of the ships, and, in fact, every man on board the telegraph fleet; have exerted themselves to the utmost to make the expedition successful, and by the blessing of Divine Providence it has succeeded.

After the end of the cable is landed and connected with the land line of telegraph, and the Niagara has discharged some cargo belonging to the telegraph company, she will go to St. Johns for coal and water, and then proceed at once to New York.

Cyrus W. Field

First Signal Received in Newfoundland

On August 9th, using instruments in the Telegraph Room at Bay Bulls Arm, Newfoundland, and in the operating room at the Slate Works at Valentia, Ireland, testing of the cable began.

The operations log at Valentia, parts of which are transcribed at the link above, records the first exchange of signals with Newfoundland as beginning at 12:24 A.M. on August 10th and continuing until 2:28 A.M.

Although time zones had not yet been standardized, Newfoundland was about four hours behind Valentia, and the timestamp of all these messages would thus have been late in the evening of August 9th at Bay Bulls Arm.

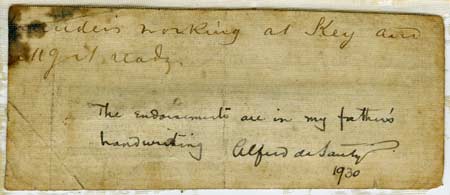

At Newfoundland, C.V. de Sauty received the first test currents sent from Valentia and recorded them on paper tape. He preserved this short section of the message tape, writing on it:

“first current

9 Aug 58”

The three-inch length of tape was then mounted on card by de Sauty, and he added this note above it:

“The very first recorded signal

from Valencia recd in Newfoundland”

On the back of the card he wrote:

“Saunders working at Key and ???g it ready”

|

Together with the other items from Bay Bulls Arm shown on this page, de Sauty gave the message tape to his son Alfred, who subsequently authenticated the tape with this note on the back of the card:

“The endorsements are in my father’s handwriting.”

“Alfred de Sauty 1930”

The Code on the Tape

The Valentia log begins with this entry:

“12.24-A.M.-Sent V’s and B’s at rate of 40 currents per minute up to 12.32”

In Morse Code, V is ...- (dot dot dot dash) and B is -... (dash dot dot dot). On other examples of message tapes from the 1858 cable stations, a dot is represented by a short bar and a dash by a long bar, so B would be recorded as — – – – and V as – – – —

The alternating sequence “V’s and B’s,” sent continuously, was used as a test signal, as noted in the Valentia log. If the opening and closing dashes of one BV group were missing from the tape, the remaining markings would be six dot bars: – – – – – – as recorded above.

In other words, the six short bars recorded on this fragment of message tape probably represent the middle section of one instance of a BV group in the first test transmission received at Newfoundland.

|

Mullaly Page 311:

St. John’s, Tuesday, August 10, 1858. Wrote to Messrs. T.H. Brooking, Sons & Co., in regard to completing Telegraph House and furnishing M. De Sauty with supplies.

St. John’s, Newfoundland, August 10, 1858.

Messrs. Brooking, Sons & Co., St. Johns:

Gentlemen:—I have to request you will, as quickly as possible, brickway cell, and otherwise finish the house in Bay of Bull’s Arms, belonging to the Atlantic Telegraph Company, and make such additions thereto as M. De Sauty may require. Also please furnish M. De Sauty with any supplies that he may order on account of the company. I remain, gentlemen, very truly your friend,

Cyrus W. Field,

General Manager Atlantic Telegraph Company.

Mullaly Page 271:

Landing of the Cable

Eighth Day – August 5.

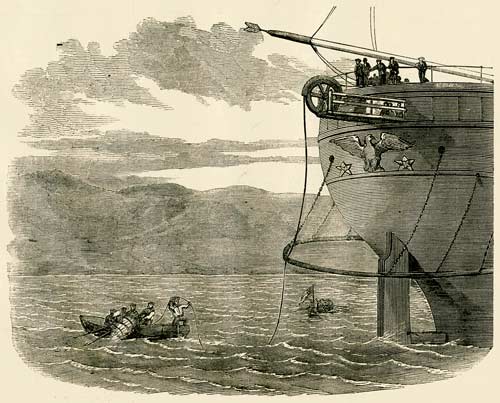

At ten minutes past two this morning preparations were made for the landing of the cable, and the Niagara is brought to an anchor for the purpose. It is still quite dark, and we can only see the outlines of the hills which tower above us on every side, showing that we are in a completely landlocked harbor.

Buoying out the telegraph cable in Bull’s Arm Bay, Newfoundland, to show where it is laid.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 11, 1858 |

As the Niagara has been brought to anchor, the cable is paid out over the machine with the aid of the little steam engine, which is put in gear with the paying-out sheaves. About a mile and a half is lowered and coiled in the boat, and by sunrise every thing is ready for the completion of the work.

Train of boats paying out the cable in Bull’s Arm Bay, Newfoundland, from the Niagara to the shore.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 11, 1858 |

The Bay of Bull’s Arm is an inlet of the sea at the head of Trinity Bay, from which it runs, between a range of irregular hills, a distance of about ten miles. Some of these hills rise to the dignity of mountains, which are in many places wooded down to the water’s edge. The inhospitable nature of the climate, combined with the barren and rocky soil, is rather unfavorable to vegetation, and the forests are composed mainly of a stunted variety of pine, which seldom attains a height of more than 30 feet; while the turf, which in some places covers the rocks to the depth of three or four feet, is overspread with a thick growth of moss. The streams, which during the summer season become mere rivulets, are converted into foaming torrents by the freshets which follow the breaking up of the long and dreary winter. Judging from the hilly and mountainous character of this part of the country, and, indeed, of the whole island, the construction and establishment of railroads in the far distant future must prove a terribly expensive affair. The landing-place for the cable is a very picturesque little beach, on which a wharf has been constructed. A road, about the dimensions of a bridle path, has been cut through the forest, and up this road, through bog and mire, you find your way to the telegraph station, about half a mile distant. Alongside of this road a trench has been dug for the cable, to preserve it from accidents, to which it might otherwise be liable.

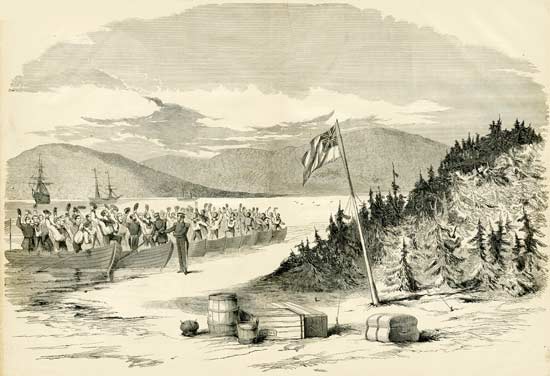

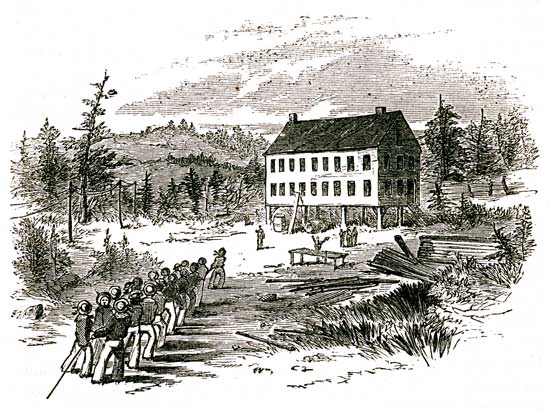

Captain Hudson landing the American end of the Atlantic Cable at Trinity Bay, at six o’clock on the morning of August 5, 1858.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 4, 1858

|

When the boats arrived at the landing the officers and men jumped ashore, and Mr. North, first lieutenant of the Niagara, presented Captain Hudson with the end of the cable. Captain Otter, of the Porcupine, and Commander Dayman, of the Gorgon, now took hold of it, and all the officers and men following their example, a procession was formed along the line. As the cable was covered with tar, the handling of it was rather objectionable, but there were none who, under the circumstances, refused to take a part in the landing. There were some, it is true, who would not at first put their bare hands to it, and who sought to protect them with gloves, or by covering the cable with moss. This movement, however, was rather unpopular; so the gloves were taken off, and although part of the moss adhered to the cable, there was little of it used afterwards.

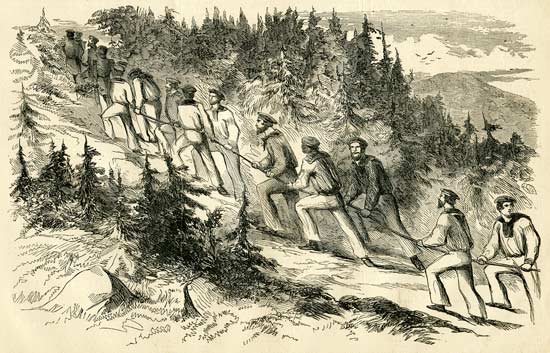

The road or path over which we had to take the cable was a most primitive affair. It led up the side of a hill a couple of hundred feet high, and had been cut out of the thick forest of pines and other evergreens. In some places the turf, which is to be found here on the top of the highest mountains, was so soft with recent rains that you would sink to your ankles in it. The road-maker or road-makers, whoever they were, had evidently done all in their power at the short notice they had to make it passable, and it is enough to say they succeeded to that extent, although we could not help wishing that they had not placed the stepping-stones so far apart, and had been a little more liberal in the use of timber. Well, it was up this road we had to march with the cable, and a splendid time we had. It was but reasonable to suppose that the three captains, who headed the procession, would certainly pick out the best parts, and give us the advantage of the stepping-stones, but it appeared all the same to them, and they plunged into the boggiest and dirtiest parts with a recklessness and indifference that satisfied us they were about the worst pilots we could have had on land, despite their well-known abilities as navigators.

Officers and sailors carrying the Atlantic Cable from

the shore to the Cyrus Telegraph Station, Newfoundland

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 4, 1858 |

This memorable procession started at a quarter to six o’clock, and arrived at the telegraph station about twenty minutes after. The ascent of the hill was the worst part of the journey, but when we got to the top, the scene which opened before us would have repaid us for a journey of twenty miles over a still worse road. There beneath us lay the harbor, shut in by mountains except at the entrance from Trinity Bay, and there, too, lay the steamers of the two greatest maritime nations in the world. On every side lay an unbroken wilderness, and if we except the telegraph station, at which we will soon arrive, not a single habitation to tell that man has ever lived here.

Never was such a remarkable scene presented since the world began. Even now, at the very point of its realization, it does not seem as if the work in which we have been engaged has been accomplished. Looking back on the past, the seven long days of anxiety and suspense appear but as one, and it is almost impossible for the mind to comprehend the great fact that the cable is really laid. It would seem like a dream, were it not for the visible, palpable evidence which we now hold in our hands, the electric chain which binds the two worlds together. No, it is not a dream, but a great reality, the announcement of which will startle the incredulous and unbelieving of both continents. The continuity, without which the cable would be utterly valueless, is as perfect now as it ever was. Mr. D. Laws and Mr. De Sauty, the two chief electricians, who have accompanied us from England, have “tasted” the current, and about a dozen others at the head of the procession have done the same thing. The writer himself is a witness on this point, and will never forget the singular acid taste which it had. Some received a pretty strong shock—so strong that they willingly resigned the chance of repeating the experiment.

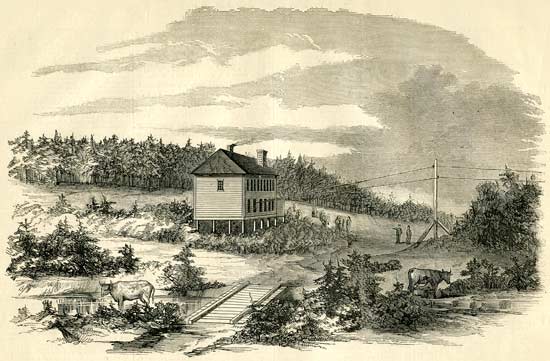

About twenty minutes after we started from the beach we reached the station of the Atlantic telegraph on this side of the ocean, where we found some half dozen of the inmates awaiting our arrival. The station is a large frame building, two stories high, and eight windows wide. On the first floor is a kitchen, an office and a sitting apartment, dignified with the title of parlor. The door opens on the side of the house, and there is no means of exit from the front, for the simple reason that the first story is eight or ten feet from the ground. This singular arrangement is explained by the fact that the building is situated on the side of a hill, and that there is a considerable difference between the height of the front and back walls.

A.T. Co’s Station House

Mullaly 1858

|

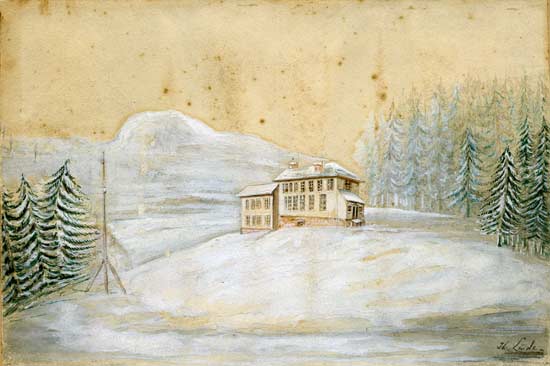

While Mullaly describes the building as “eight windows wide”, his artist has shown it with nine windows on each floor in the sketch above. In Theodor Linde’s watercolour below, the building has eight windows on the second story and six on the first. The station also looks somewhat more finished: its foundation is filled in (perhaps the “brickway cell” that Cyrus Field had requested) and an entrance vestibule has been added at the right:

The Cable Station in Summer

(Atlantic Telegraph Company Building)

Watercolour by Theodor Linde, 1858 |

The second story is divided into sleeping apartments separated by a single corridor, and the whole establishment will lodge about two dozen persons. A beginning has been made in the clearing away of the forest in the immediate vicinity of the house, and in the course of a year, they will have as pleasant and as comfortable a dwelling perhaps as any in Newfoundland, although it may not have all the luxuries of civilized life. Of the details of domestic life at the telegraph station more will be said hereafter. Meantime we must continue the particulars of our narrative.

On the arrival of the procession the cable is brought up to the house and the end placed in connection with the instrument. The deflection of the needle on the galvanometer gives incontrovertible evidence that the electrical condition of the cable is satisfactory.

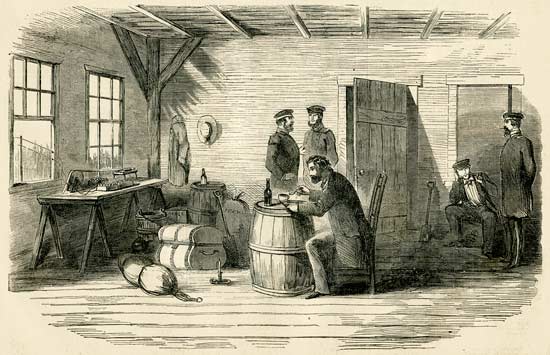

View of the operators’ room at Cyrus Station, immediately after the landing of the American end of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 11, 1858 |

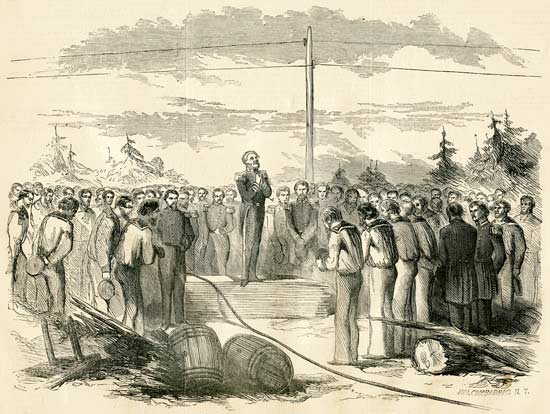

The question now is, how shall we properly celebrate the consummation of the great event? How, but by an acknowledgment to that Providence without whose favor the enterprise must have ended in disaster and defeat. Every one feels that this is all that is necessary to make the celebration complete, and to mark the undertaking as the work of two great Christian nations. When, therefore, they all gathered together before the telegraph station, they understood the purpose for which they were assembled. Captain Hudson took up his position on a pile of boards, the officers and men standing round amid shavings, stumps of trees, pieces of broken furniture, sheets of copper, telegraph batteries, little mounds of lime and mortar, branches of trees, huge boulders, and a long catalogue of other things equally incongruous.

Capt. Hudson offering up prayer in front of the Cyrus Telegraph Station, Newfoundland, after himself, officers and sailors of the Atlantic Cable Squadron had brought the cable to that spot.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 4, 1858 |

At the close of the foregoing remarks the audience of “cable layers” dispersed, some to amuse themselves in short excursions about the grounds adjoining the station, and others to explore the mysteries of the building itself. About an hour after, the captain, officers and men assembled on the beach where the cable had been landed, and where they re-embarked for their several ships.

Mullaly Page 281:

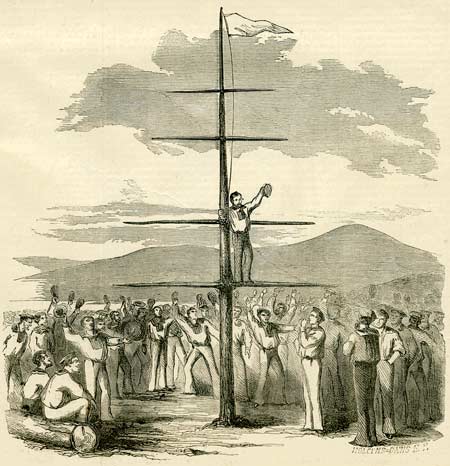

How the Crew of the Niagara Celebrated the Success of the Enterprise.

During the forenoon of the day on which the cable was landed [August 5th 1858], the greater part of the crew of the Niagara was permitted to go ashore and amuse themselves as well as they might in a perfect wilderness. And - never did the crew of any vessel enjoy themselves with more zest under the circumstances—it was different from their shore experience in other places, but the novelty only served to increase the pleasure. Some amused themselves in explorations over the hills and through the forests; others in piscatorial excursions up the trout streams; others in swimming; while others commemorated the occasion by erecting a mast near the point where the cable was landed, and dignified the place with the title of “Niagara City.”

There were no lots marked out, it is true; no boundaries, nor any thing of that kind; but there may be at some future day, and if the inhabitants do not retain the name, they don’t deserve to have a city—that’s all. The portion of the crew who assisted in this work numbered about a hundred altogether, and among these was a considerable body of the firemen, under the charge of Mr. Sexton, the engineers’ storekeeper. The high officiating personage on the occasion—in fact the founder of the future city—was John McMath, one of the sailors, and just the man to take the lead in such a movement. McMath resolved in his own mind that something more should be done to commemorate the great event in which he and his messmates had played a part, however humble, and acting upon this determination, he gathered a large number of the crew together, and addressed them on the subject. When they were all assembled he spoke in substance as follows:

“Now, boys, we are all here, and I want to say a few words to you. We have laid the cable. (Cries of yes, yes, and hurra). Yes, boys, we have laid the cable, and that’s a fact, this time—no mistake now. (A voice—that’s true, any way. Give us some more of that kind of talk, Mac.) It’s down, and it’ll stay down where we have put it. (Another voice—they’ll have a job to lift it—that’s all). Now, what I want to say to you is this—(Aye, aye). I want the people who come here to know, that the Niagara’s boys have been here before them, and that it was they that laid the cable. No objections to that. (No, no, from a hundred tongues). Well, then, I have got something to propose. (What is it ?—what is it ?) I propose that we raise a mast on this very spot, and when we have got it up, that we shall call the place all round about “Niagara City.” Are you all agreed ? (Aye, aye, we’re with you, Mac.)

The sailors of the Niagara erecting a liberty pole at Bull’s Arm Bay, Newfoundland, and naming the spot “Niagara City” to commemorate the successful laying of the cable.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 4, 1858

|

At the close of this brief, but pithy and forcible address, they all unanimously decided that McMath should be the leader, and the better to perform his part he manufactured from the branch of a tree a boatswain’s whistle, with which to direct the men in putting up the mast and rigging. Under his direction they went to work at the forest, selected the tallest pine, put a rope around it, and tugged and pulled till they dragged it up by the roots. They then cut off the branches, until nothing remained but the straight trunk of the tree, which they planted firmly in a deep hole they had dug for the purpose. This part of the work performed, they tore down several other trees to make yards for the mast. There was the main-yard, the maintop-yard, the main-top-gallant, and the main-royal-yard, and above these all floated the flag, which they extemporized for the occasion, and which bore the simple inscription “Niagara.” At the close of their work, they gave three cheers, and separated, but the raising of the mast, and the founding of “Niagara City,” furnished the subject of conversation among the crew for many days after.

Mullaly Page 286:

A Visit to the Telegraph Station.

The road which leads from the beach up to the telegraph station has already been described, and the reader is therefore aware that it is not the most inviting for those who are fond of rapid travelling. But it is a short road, and the passage over it is neither dangerous nor difficult, although the bog holes are but partially filled up, and the person who would undertake to walk over it with clean shoes would be somewhat disappointed at the end of his journey. At one end of this road, within a few feet of the beach, stood the telegraph station, before it was removed on the day the cable was landed. There was neither house nor log cabin there, and were the spectator not informed that the station had occupied a particular spot, he would have some difficulty in finding the precise place where it was located. The station was simply two upright poles planted in the earth, and rising to a height of about three and a half feet, and having a board three feet long and five inches wide nailed on top. Upon this a small instrument for transmitting messages was placed, and on this instrument Mr. McKay, the Superintendent of the lines of Newfoundland, operated. He took it down soon after the cable was landed, put the instrument in his pocket, and literally speaking, walked away with the station.

New York and Newfoundland Telegraph Station

Mullaly 1858

|

It would, however, have been a somewhat difficult matter to dispose of the Atlantic telegraph station in the same manner, and the man who should undertake the task would have had a Herculean labor to perform. The reader has been made acquainted with the fact that it is built on the side of a hill; that it has but one door, and that opens on the side; that it is two stories high, with a parlor, a kitchen, and several bedrooms; that it is constructed mainly of wood; that it is five miles from the nearest house and fifteen miles from the nearest village; that an attempt has been made to clear away the wood which hems it in on almost every side, and finally, that it is in the midst of a perfect wilderness; but as yet he knows nothing of the wonderful domestic life that exists inside of that same house, and of the strange doings that take place therein, especially in the culinary departments.

I may begin by stating that there are eleven occupants, and when I say that these occupants are all of the masculine gender, the reason why things are not as they ought to be in that house will at once become apparent. No man ought to be surprised, for instance, if the bread is not well baked, the meat not sufficiently cooked, the tea too weak or too strong, the potatoes—whenever they get them—boiled to smash, or not boiled at all, or if the fire requires to be kindled at least half a dozen times a day. Nor should they be astonished if the beds are not made till the occupant is just ready to get into them; and if, according to the same system, the table utensils are not cleaned till every thing is cooked and ready to go on the table. All this is explained by the fact that there are no women to attend to these things, and if the Telegraph Company should permit the operators to live as they now are, their relapse into a state of semi-barbarism, so far as the domestic usages of civilized life are regarded, is only a question of time.

Imagine eleven or twelve young men thrown for the first time on their own resources, endeavoring to cook for themselves, to wash the dishes, to sweep the floor, to make the beds, to light the fires, and to perform the hundred and one little things of which men know nothing, but which, with those other “trifles,” make up that greatest of all blessings—a comfortable and a happy home. Imagine, in fact, a man attempting to perform the part of woman in his clumsy, ungainly way, and you have some idea of what a house full of men can effect in this line, and of the condition of the domestic portion of the Atlantic telegraph station in particular. What a scene of confusion in the kitchen, what a terrible state of things in the half furnished parlor, without a sofa, and with a few boxes and trunks for seats! what a frightful chaos in the dozen little bedrooms up stairs, where the blankets and sheets and pillows are rolled up in one mountainous lump, or so twisted about as to furnish a good half hour’s work to the occupant to get each into its proper place again!

But with all this confusion, the electricians and operators are as fine a set of fellows as ever lived in one house, and live more cheerfully and happily in the midst of discomforts than many in the Fifth Avenue, who can boast of all the luxuries and appliances of civilized life. It would be unjust to bring them to account if their domestic education has been neglected; and if, among other things, they did not learn to bake bread and to cook a beef-steak properly, it is not their fault, although, in this instance, it is their misfortune. What matter if they do not know how long it takes to boil an egg, if they can translate the language of electricity, and send a message along the cable that now lies extended on the bed of the ocean between two continents? And if the company have not every thing provided for them, they can “wait a little longer” for the “good time coming”—a time that is to bring with it a piano and billiard table to while away their leisure hours—a time when the parlor shall no longer want a sofa, but when it shall shine forth in all the refulgence of a pier glass, one mahogany table, perhaps two—the company can afford to be liberal now that the cable is laid—a dozen handsome mahogany chairs, some ornaments for the mantelpiece, a stool for that piano, a substantial Brussels carpet with a handsome pattern, a hearth rug, new style, with a landscape, a lamblike lion, or ferocious tiger, in the centre; an accurate timepiece, in a neatly carved frame; and all the other articles that make up a well-furnished parlor.

It may be asked what will they want with all these in the midst of a wilderness? The answer is very simple —they want them to keep them in mind of what civilized life is like, and of the homes which they have left behind in the Old World. With a parlor furnished in the manner described, they will require few other things, except some paintings to decorate the walls, and these the talented artist who belongs to the corps of operators will supply with his brush and palette.

Then, after the company have attended to the parlor, or rather before they have attended to it, they must look out for the kitchen arrangements, the culinary utensils, and all that. They must provide a pan or pans, so that the volunteer cooks may not be obliged to use the pot for the double purpose of boiling and frying; they must furnish more than one kettle, so that if the spout or handle should happen to be knocked off they may not be reduced to extremities. It will, however, assuredly be gratifying to the benevolent housekeepers of New York, and indeed of all Christendom, to know that the domestic difficulties which these same electricians and operators have encountered will soon be brought to an end, as a cook was on his way from St. Johns to take charge of the culinary department when we were about leaving that city.

It is true the four occupants of the station who resided there before the arrival of the Niagara, did not take as much interest in the preparation of the house for the reception of the expected ones as they might have done, but, in extenuation of their neglect, it must be stated that they had given up all hope of ever seeing such a wonderful thing taking place, and as for the expected ones, they had long ceased to be expected. If, however, whether excusable or inexcusable, they did not attend to the few matters to which they could attend, there is no excuse for the company, should they neglect to furnish them with every thing necessary in the department now under our consideration, and to which we intend to direct their attention with all the particularity of which our knowledge of such matters will admit.

In the first place, then, they must put a grate in the kitchen—that every cook considers almost indispensable. The next thing is an oven, and when this is put up, they will want toasting and roasting apparatus, chairs instead of hard boxes and harder blocks to sit upon—blocks which are particularly objectionable to men of tender and delicate feeling. It is needless to repeat the various things that the kitchen of the telegraph station will require to make it complete, but the directors of the company have only to get an inventory of what their own kitchens contain, to be aware of the wants of the operators and to be enabled to supply them. The cook, there is no doubt, will prove a perfect treasure to them, and that same cook will hear of efforts in cooking before he is long in the station that will astound him.

Just think, oh! ye housekeepers of New York, who have been so often appealed to already, just think of Christian men putting a large lump of pork into a pot not big enough to hold one half the quantity, and that pot about one-third full of water! Is it any wonder that the water should all boil away, and that the bottom of the pot, becoming red hot, should set the pork in a blaze? Is it any wonder that this should occur, and that the cooks should throw a whole pailful of water, fill the pot to overflowing, and put out the fire altogether? What would you think of men who set out with the intention of making what they called a plum dumpling, and who were obliged, by their own incapacity and utter ignorance of the great art of cooking—an art that has immortalized a Soyer and a Murray—to leave the dumpling unfinished, and then endeavor to convert it into a series of pancakes? Just think of it, pancakes with plums in them, and those plums so battered and bruised that the stones would persist in appearing where they were not wanted, right on the top of the flattened surface. But the cook will set every thing to rights, and take care, when the pork is boiling, the fat does not get into the fire. He will also see to it, that when dumplings are commenced they do not end by becoming doubtful pancakes.

Now these little domestic mishaps and troubles are, after all, not such troubles as might be supposed, but furnish material for many a good joke to the dwellers at the station. They have plenty to eat, for the company are determined that, though there should happen to be a famine in Newfoundland, they shall not want. They have also a capital barrel of ale, and there is the best water in the island within a few feet of the building. There is no lack of fuel, for firewood is abundant all around them, and they can cut down sufficient in a day to last them for a month. In addition to all this, there is plenty of game in the valleys and on the mountains, while the sea, near the coast, swarms with fish, and the streams are alive with trout. Newfoundland is in fact the sportsman’s paradise, and when the Nimrods of the United States come to find it out, they will rush there in crowds during the summer months. What do they think of catching forty trout in the course of an hour and a half, and of taking them all from the one spot, in a stream not more than two yards wide in its widest part? What do they think of performing this feat with a rod made of the crooked branch of a tree, without a reel, and the hook baited with a piece of mutton? This feat the writer himself performed, and he willingly testifies that the trout was the finest he ever tasted—vastly superior to the wretched affairs called brook trout, which many of the Broadway restaurants serve up at a dollar apiece. There are bears, too, in the island, affording fine sport for those who are fond of the rougher kind of game, and the wolves sometimes become so bold that they break into the farm-yards and kill the cattle. The deer, or the kariboo as it is called, affords very good venison, and there are several varieties of feathered game. All things considered, it will be seen from this that’ Newfoundland is not such a dreary, desolate place to live in, and that if the telegraph station is situated in the midst of a wilderness, it is one that is not devoid of distractions.

There is one particular part of the building which has not yet been alluded to, but which is, after all, the most important. This is the electricians’ office, in which all the telegraphic instruments have been put up. There are the batteries, which bear the same relation to the wire conductor that the boilers bear to the steam engine; and there the delicate apparatus by means of which the weight or force of the electrical current is told to a nicety; there, too, the needle, which tells whether the continuity or insulation is perfect. There, in a word, are all the instruments which were put on board the Niagara, and which, having served their purpose well, have been transferred to the telegraph station at Trinity Bay. The office is also furnished with a clock which keeps Greenwich time, and in the event of its running down there are half a dozen chronometers by which to set it right again. Take it altogether, the electricians’ office is the best arranged part of the whole establishment, and presents a strong contrast to the kitchen and parlor, both of which the company must have well furnished.

The telegraph house has been called “Cyrus Station” by the electricians, in honor of Mr. Cyrus W. Field, and will hereafter be known by that title. It could not receive a more appropriate one, and will help to perpetuate the name of a man who has done more than any other to make the Atlantic telegraph a grand reality.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper published this description of the building in its issue of 21 August 1858, although from the wording of the report, it must have been written some time earlier. At present it is not known exactly when the station building was erected.

At the head of the Bay of Bull’s Arm, about half a mile from high-water line, the telegraph-house will be erected. This will be a spacious frame building, containing, in addition to the office or operators’ department, a sitting-room, a kitchen, eight bedrooms, and all the other et ceteras of a well-appointed household. It is the intention of the company to provide the operators with a library; and if they do not have enough to interest them in what they will find in it, in themselves, in the country, and in their business, they will be hard to please indeed. The force of operators will number seven, and these must have, among other qualifications, a perfect knowledge of French, German, Italian and English, so that they may be enabled to receive and transmit messages in all those languages. In addition to the operators, there will be five mechanics to repair the telegraph instruments, and to perform any other work that may be required of them in their particular trade.

The September 4th 1858 issue of the newspaper had an extensive article on the landing of the cable at Newfoundland which included this illustration of the station building. The view is from a different angle, but the details correspond with Theodor Linde’s summer watercolour above.

Cyrus Telegraph Station, Bull’s Arm Bay,

Newfoundland,

the American Terminus of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable.

From a sketch by our own correspondent,

who accompanied the expedition.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Sept. 4, 1858 |

The 1858 Atlantic cable worked only intermittently, and on September 1st, after five days of testing and twenty-three days of fitful operation, the cable was dead. During that period 129 messages had been sent from Valentia to Newfoundland, and 271 in the opposite direction. For a detailed transcript of the messages, see Tal Shaffner’s evidence in the Report of the Joint Committee of Inquiry into the Construction of Submarine Telegraph Cables, published in 1861.

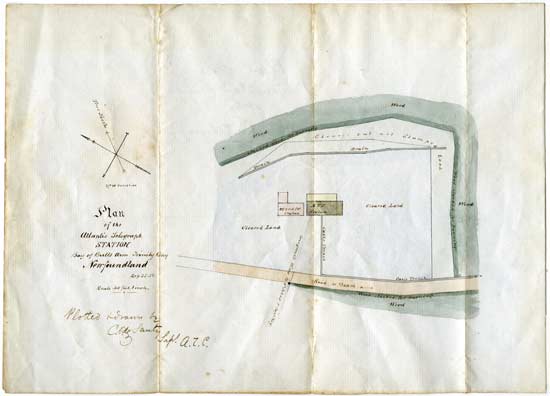

After the failure of the cable both the Valentia and Trinity Bay stations were each operated by a much-reduced staff, who periodically tested the circuit for any signs of life. On September 25th 1858 C.V. de Sauty made this site plan: “Plotted & drawn by C.V. de Sauty, Supt. A.T.C.”

Plan of the Atlantic Telegraph Station

Bay of Bulls Arm, Trinity Bay

Newfoundland

Sep 25 . 58

Scale 40 feet . 1 inch

Plotted and drawn by C.V. de Sauty, Supt. A.T.C.

Pen & ink with watercolour highlights

|

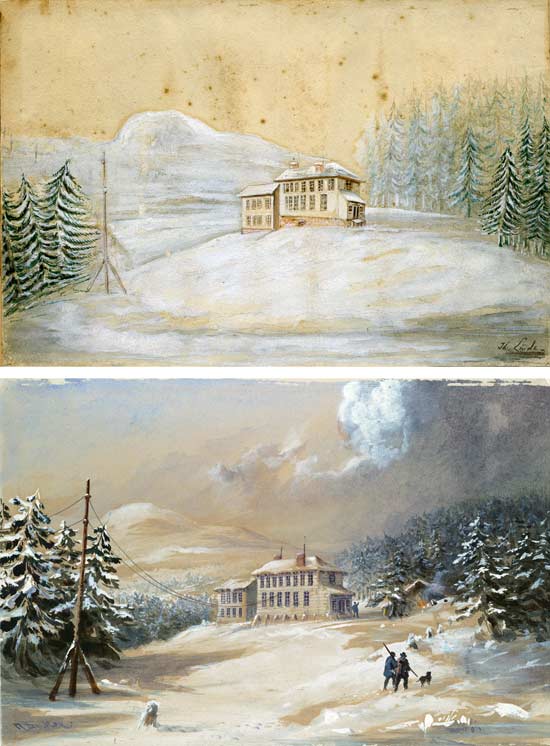

Theodor Linde also evidently stayed in Newfoundland at least until the winter, as he made one final watercolour of the station, which, as shown on de Sauty’s plan above, now included a second building. This was the office of the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company, immediately to the left of the original Atlantic Telegraph Company building.

The Cable Station in Winter

(Atlantic Telegraph Company building on the right)

Watercolour by Theodor Linde, 1858 |

For William Russell’s book The Atlantic Telegraph, which was published at the end of 1865 following the unsuccessful Atlantic cable expedition of that year, the official artist, Robert Dudley, painted a number of scenes of the 1858 enterprise, including two views of the cable station at Bay Bulls Arm. However, Dudley had no involvement with the Atlantic cable enterprise until he sailed on the Great Eastern expedition in 1865, and he did not visit Newfoundland until the conclusion of the 1866 expedition. Accordingly, his 1865 paintings of the 1858 cable station must have been based on earlier works by other artists.

By 1865 both Theodor Linde and C.V. de Sauty had returned to England. No later than 1861, Linde had left the telegraph service and was engaged in the jewellery business [UK Census records]. Although Linde kept in contact with Cyrus Field [1867 letter from Field to Linde], there is no evidence that he ever met Robert Dudley. However, in 1865 C.V. de Sauty was in the employ of the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company, for which he was Chief of the electrical staff on that year’s Great Eastern Atlantic cable expedition. As Dudley was official artist on this same voyage, it is quite possible that de Sauty showed him Linde’s watercolours, and Dudley then used them as a reference for his own renditions of the 1858 Newfoundland station.

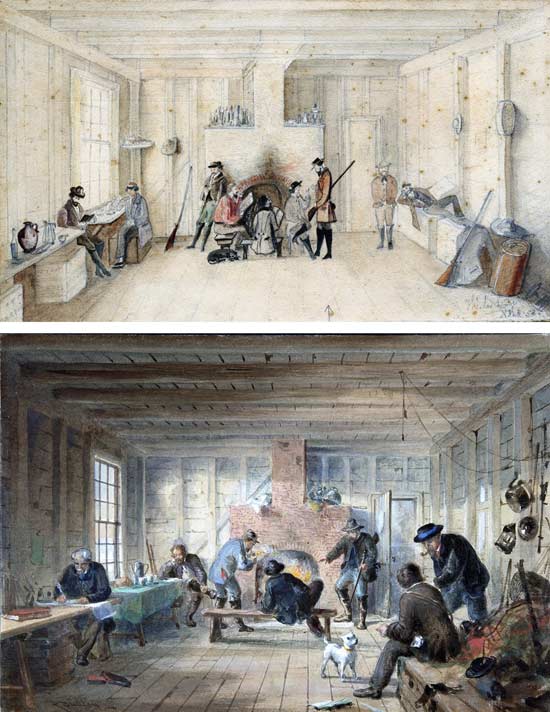

Here are comparisons of two of the scenes used in Russell’s book. Linde’s work is on top, Dudley’s on the bottom in each pair of images.

Winter View of the Telegraph House, 1858

Bottom image by Robert Dudley courtesy

of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

| |

Telegraph House, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland:

Interior View of the Mess Room, 1858

Bottom image by Robert Dudley courtesy

of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Dudley’s view of the cable station in winter is so similar to Linde’s version that it must be a direct copy, and Dudley’s messroom scene also has many similarities.

As noted earlier, all that remains of the 1858 buildings are some parts of the foundation. This photograph on the Inside Newfoundland and Labrador Archaeology site was taken in 2014, and there is a brief description of the remains on their Southern end of Trinity Bay post.

Foundation of the former telegraph station near Sunnyside

Image link courtesy of NLArchaeology |

These views of the site in 2013 are courtesy of Pat Farrell of Sunnyside:

Foundation of the former telegraph station near Sunnyside

Images courtesy of and copyright © 2016 Pat Farrell

|

Charles V. de Sauty

1830-1893

Although little has been written about him, Charles Victor de Sauty, almost invariably referred to as C.V. de Sauty (and sometimes erroneously as “de Santy” in the literature of the time), was one of the significant figures in early cable telegraphy. This obituary was published in The Electrician, April 14, 1893:

We regret to have to record the death, at the age of 63, of Mr. Charles Victor de Sauty, which took place from paralysis on the 11th inst. at Gibraltar, where he was Superintendent of the Eastern Telegraph Company.

C.V. de Sauty in 1865

Image courtesy of IET, from the

Knight of Kerry’s scrapbook |

The deceased was born in 1830, and after some time spent in a solicitor’s office, entered the Submarine Telegraph Company’s service. In 1856 he joined the original Atlantic Telegraph Company, and was Superintendent of the Newfoundland Station during the short period the cable worked in 1858, and in the laying of which cable he took part as electrician. In 1859 he joined the firm of Glass, Elliot and Co., afterwards the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, as their chief electrician, and was engaged upon all the expeditions for the laying of that firm’s cables up to 1865, including the Atlantic cable of that year. He then went to New Zealand, and was in charge of the Government Telegraphs there until 1870, when he entered the service of the Falmouth-Gibraltar and Malta Telegraph Company, which was afterwards amalgamated, with three other companies, into the Eastern Telegraph Company.

Although Mr. De Sauty had no regular training in that direction, he was a most ingenious mechanician and kept well in the van of all the early developments of electrical science and submarine telegraphy, in proof of which may be cited his method for the comparison of electrostatic capacity, which was the earliest differential method used for that purpose and contained within it the elements of the duplex. Mr. De Sauty was largely concerned in the practical development of the duplexing of cables which was finally perfected by the introduction of Dr. Alexander Muirhead’s condensers. His name was better known on the American side, in connection with the laying of the first Atlantic cables, than that of any other member of the scientific staff, as is evidenced by the quaint verses of Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes which we have reproduced below. Mr. De Sauty was a man of strong personal character, expressing his opinions very plainly, and one of the staunchest friends it was possible to have. His loss will be regretted by a wide circle of acquaintances.

See the full text below of Oliver Wendell Holmes’s “quaint verses” on de Sauty.

In 1888, Cyrus Field’s brother Henry M. Field, who wrote a number of travelogues, published a book on Gibraltar, where he had spent the first part of 1887, sailing from there to Africa later in the year. Having written extensively on the first Atlantic cables, on arriving at Gibraltar Henry took the opportunity to look up Charles de Sauty, about whom he wrote:

Readers whose memories run back thirty years to the laying of the first Atlantic Cable in 1858, may recall the fact that the messages from Newfoundland were signed by an operator who bore the singular name of De Sauty, and when the pulse of the old sea-cord grew faint and fluttering, as if it wore muttering incoherent phrases before it drew its last breath, we were accustomed to receive daily messages signed “All right: De Sauty!” which kept up our courage for a time, until we found that “All right” was “All wrong.” The circumstance afforded much amusement at the time, and Dr. Holmes wrote one of his wittiest poems about it, in which the refrain of every verse was “All right: De Sauty!” Well, the message was true, at least in one sense, for De Sauty was all right, if the cable was not. The cable died, but the stout-hearted operator lived, and is at this moment the manager of the Eastern Telegraph Company in Gibraltar. This is one of those great English companies, which have their centre in London, and whose “lines have” literally “gone out through all the earth.” Its “home field” is the Mediterranean, from which it reaches out long arms down the Red Sea to India and Australia, and indeed to all the Eastern world. Its General Manager is Sir James Anderson, who commanded the Great Eastern when she laid the cable successfully in 1866. I had crossed the ocean with him in ’67, and now, wishing to do me a good turn, he had insisted on my taking a letter to all their offices on both sides of the Mediterranean, to transmit my messages free! This was a pretty big license; his letter was almost like one of Paul’s epistles “to the twelve tribes scattered abroad, greeting.” It contained a sort of general direction to make myself at home in all creation!

With such an introduction I felt at home in the telegraph office in Gibraltar, and especially when I could take by the hand our old friend De Sauty. He has a hearty grip, which speaks for the true Englishman that he is. If any of my countrymen had supposed that he died with the cable, I am happy to say that he not only “still lives,” but is very much alive. He at once sent off to London a message to my friends in America—a good-bye for the old year, which brought me the next morning a greeting for the new.

DE SAUTY

by Oliver Wendell Holmes

(“The Professor”)

The following poem is my (the Professor’s) only contribution to the great department of Ocean-Cable literature. As all the poets of this country will be engaged for the next six weeks in writing for the premium offered by the Crystal-Palace Company for the Burns Centenary, (so called, according to our Benjamin Franklin, because there will be na’ry a cent for any of us,) poetry will be very scarce and dear. Consumers may, consequently, be glad to take the present article, which, by the aid of a Latin tutor and a Professor of Chemistry, will be found intelligible to the educated classes.

| DE SAUTY |

| An Electro-Chemical Eclogue. |

| Professor. |

Blue-Nose. |

PROFESSOR

Tell me, O Provincial! speak, Ceruleo-Nasal!

Lives there one De Sauty extant now among you,

Whispering Boanerges, son of silent thunder,

Holding talk with nations?

Is there a De Sauty ambulant on Tellus,

Bifid-cleft like mortals, dormient in nightcap,

Having sight, smell, hearing, food-receiving feature

Three times daily patent?

Breathes there such a being, O Ceruleo-Nasal?

Or is he a mythus, --ancient word for “humbug,” --

Such as Livy told about the wolf that wet-nursed

Romulus and Remus?

Was he born of woman, this alleged De Sauty?

Or a living product of galvanic action,

Like the acarus bred in Crosse’s flint-solution?

Speak, thou Cyano-Rhinal!

BLUE-NOSE

Many things thou askest, jackknife-bearing stranger,

Much conjecturing mortal, pork-and-treacle-waster!

Pretermit thy whittling, wheel thine ear-flap toward me,

Thou shalt hear them answered.

When the charge galvanic tingled through the cable,

At the polar focus of the wire electric

Suddenly appeared a white-faced man among us:

Called himself “DE SAUTY.”

As the small opossum held in pouch maternal

Grasps the nutrient organ whence the term mammalia,

So the unknown stranger held the wire electric,

Sucking in the current.

When the current strengthened, bloomed the pale-faced stranger,

Took no drink nor victual, yet grew fat and rosy, --

And from time to time, in sharp articulation,

Said, “All Right! DE SAUTY.”

From the lonely station passed the utterance, spreading

Through the pines and hemlocks to the groves of steeples,

Till the land was filled with loud reverberations

Of “All Right! DE SAUTY.”

When the current slackened, drooped the mystic stranger, --

Faded, faded, faded, as the stream grew weaker, --

Wasted to a shadow, with a hartshorn odor

Of disintegration.

Drops of deliquescence glistened on his forehead,

Whitened round his feet the dust of efflorescence,

Till one Monday morning, when the flow suspended,

There was no De Sauty.

Nothing but a cloud of elements organic,

C. O. H. N. Ferrum, Chlor. Flu. Sil. Potassa,

Calc. Sod. Phosph. Mag. Sulphur, Mang.(?) Alumin.(?) Cuprum, (?)

Such as man is made of.

Born of stream galvanic, with it he had perished!

There is no De Sauty now there is no current!

Give us a new cable, then again we’ll hear him

Cry, “All Right! DE SAUTY.”

|

Alfred de Sauty

1870-1949

C.V. de Sauty’s son Alfred was a bookbinder who produced tooled bindings of exceptional delicacy; he was active in London from approximately 1898 to 1923, and in Chicago from 1923 to 1935. Born in Gibraltar, he was the son of a distinguished engineer and studied engineering himself for a time. He gave it up for bookbinding and although he was not apprenticed in the trade, he worked as a finisher at Riviere’s and designer for the Hampstead Bindery before starting on his own. For some years he taught at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, being succeeded there by Charles McLeish the younger when he emigrated to the United States. He eventually managed the hand bindery of R. R. Donnelly in Chicago.

[The information above was compiled from notes by Davis Brass and Maggs Brothers. A more detailed account of Alfred de Sauty’s life may be found at Bowley’s Bear Faced Blog, where it is noted that he worked as a junior electrician for the Eastern Telegraph Company beginning around 1887 when he was seventeen years of age, and served on the company’s ships for eleven years, travelling around Africa and India.

The only published account of Alfred’s life and work is Marianne Tidcombe’s 8-page article “The Mysterious Mr de Sauty” in David Pearson’s

book For the Love of the Binding: Studies in Bookbinding History Presented to Mirjam Foot.]

Theodor Linde

1834-1908

The watercolours of the 1858 cable station at Bay Bulls Arm shown on this page are the only known works by Theodor Linde. He was born in Rotterdam, Holland, in 1834 and subsequently emigrated to England. The Kelvin archive at Glasgow has documents which show that Linde was employed in 1857 as a telegraph clerk by the Atlantic Telegraph Company in England, and in 1858 as a telegraphist for the New York, Newfoundland & London Telegraph Company at St John’s, Newfoundland. [1]

In 1858 Linde sailed on the USS Niagara as one of the “manipulating clerks” in the Electricians’ Department on board ship. On 2 July 1858, while at sea during the first expedition that year, C.V. de Sauty and J.C Laws sent a message over the cable to the Directors of the Atlantic Telegraph Company in London which included this statement: [2]

We cannot speak too highly of the system used for signalling, and can suggest no alteration or improvement, as we were not in the slightest degree embarrassed during the whole time that the Cable was being submerged.

We are also very much pleased with the way in which the manipulating clerks, viz. Messrs. Smith, Gerhardi, Irwin, and Linde, and Messrs Murray, McFarlane, and Morrison attended to their duties. They did everything required of them most cheerfully and readily, and gave us every assistance in their power.

Linde continued to work as a telegraphist after the cable was finally landed in Newfoundland in early August 1858, and while stationed there he made four watercolour paintings of the cable buildings at Bay Bulls Arm. These are all dated 1858 and are variously signed T. Linde, Th. Linde, and Theodor Linde [3]. He used both Theodor and Theodore for his first name in subsequent years, as well as several variations of his last name.

Marriage records show that Theodore Vander Linde and Elizabeth Mary Granville were married at Stoke Damerel, Devon, in March 1859. Linde next appears in public records on the 1861 UK census, where he is listed as Theodore H. Vanderlin, age 27, born Rotterdam. As the census that year was taken in early April, Linde must have been born in the first quarter of 1834. He is living in the household of Samuel Granville, Watchmaker, and Samuel’s wife Elizabeth, and is married to their daughter Elizabeth Mary, age 20. His occupation is recorded as Jeweller.

We see from these records that by 1861 Linde had left the cable service (presumably after the failure of the 1858 cable and the termination of operations in Newfoundland later that year), settled in England, married, and taken up a new profession. Despite these radical changes, Linde evidently maintained an interest in telegraphy and the Atlantic cable. He corresponded with Cyrus Field, and quite possibly met with Field in England during the 1860s [4]. He also gave at least three lectures on the cable, in 1865, 1867 and 1868 [5].

On the 1871 census, Theodore and Elizabeth are at 42 Fore Street, Devonport [Plymouth], and have two sons, Harold and Arthur. Theodore’s occupation is again Jeweller and the Where Born column has “Naturalized British Subject / Holland.” His father-in-law Samuel Granville is deceased, and Theodore is in partnership with his mother-in-law, the family business name becoming Granville and Linde, Silversmiths. But by August 1872 the company was the subject of “Proceedings for Liquidation by Arrangement or Composition with Creditors,” [6] and its remaining assets were sold at auction in 1876 and 1877 [7].

In the 1872 liquidation notices for his Silversmiths business with Elizabeth Granville, Linde was additionally described as a “Medical Galvanist” operating at Bank of England Place, Plymouth. At the same time Linde summoned a meeting of “the separate creditors of the above-named Theodore Linde,” but there are no further records of these proceedings [6].

Between September 1872 and June 1874 Linde placed regular advertisements in a number of local newspapers in Devon. These offered his services as a medical practitioner: “Dr Theodore Linde, Ph.D, Medical Galvanist and Electrician.” In some of the advertisements he listed this qualification: “Anatomical Medallist, Royal Academy, Holland, 1850”[8], although he would have been only about sixteen years old at that time. He also offered for sale “Dr. Linde’s ACME GALVANIC MACHINE, Price £3 5s., £3 5s., and £5 10s., constructed for professional and private use, combines every desideratum, and is unsurpassed as an electro-therapeutic instrument.”

On the 1881 census Theodore’s occupation is now Physician & Surgeon. While there are no records of what he did after his Medical Galvanist work in the 1870s, a notice published on his death in 1908 makes it clear that he continued in the medical profession (see below).

In June 1888, Cyrus Field wrote a letter to “Mr A. van der Linde” in Brooklyn, responding to a request from Linde for a brief meeting: “If you will call some day about two o’clock to see me, I can give you an interview of a few minutes.”[9]

Arthur van der Linde had emigrated to the United States in 1886, and he lived in New York City until moving to Toronto in 1931 to join his brother Harold. Perhaps Theodore Linde had suggested to his son that he should meet with Field; the subject of the meeting is unknown, but Field’s tone in the two-sentence letter is formal.

On the 1891 census Theodore is in Lydbrook, Gloucestershire, occupation Doctor & Surgeon, while his wife Elizabeth is visiting relatives near Plymouth with their elder son Harold. On 23 October that year Linde placed a help wanted advertisement: “Groom and Gardener Wanted; one horse and small greenhouse.”[10] The position included the use of a two-roomed cottage at “Lydbrook House, near Ross, Herefordshire,” so Linde was evidently quite well situated at that time.

Various reports in area newspapers during the 1890s show that he was a general practitioner and was often called out to attend accident victims.

On the 1901 census Theodore and Elizabeth are at Lydbrook House, Lydbrook, Gloucestershire. They have two servants, a housemaid and a cook, and at age 67 Linde is still a Doctor of Medicine.

In 1908, it was reported at a meeting of the Westbury-on-Severn [Gloucestershire] Board of Guardians that the death had occurred on July 27th that year of Dr. Theodor Linde, “who was appointed medical officer of Joys Green Ward on the 2nd July, 1895.”[11] His age would have been 74.

The England & Wales National Probate Calendar has this entry:

LINDE Theodore of Lydbrook House Lydbrook Gloucestershire doctor of medicine died 27 July 1908. Probate Gloucester 22 August to Elizabeth Mary Linde widow. Effects £1692 1s. 7d.

In the Monmouth registration district, which at that time included parts of Gloucestershire, the death register for the third quarter of 1908 has an entry for Theodor Pierre Van der Linde, aged 74. This is obviously the same Theodore Linde under his full legal name, confirmed by a death record for his wife, Elizabeth M. Van der Linde, aged 84, at Croydon in September 1924.

Here are the variations of his name as recorded in documents ranging between 1858 and 1908:

Theodor Linde

Theodore Vander Linde

Theodore H. Vanderlin

Theodore Linde

Theodor Pierre Van der Linde

Notes:

1. University of Glasgow Kelvin Papers: MS Kelvin A37; MS Gen 1752/5/1/W/3/1; MS Kelvin A50

2. Briggs & Maverick: “The Story of the Telegraph, and a History of the Great Atlantic Cable...” p.166

3. The watercolours were originally in the possession of C.V. de Sauty

4. Letter from Cyrus W. Field to Theodor Linde at 48 Fore St, Devonport, May 23 1867. Private collection.

5. Western Morning News, 10 October 1865; Western Morning News, 14 January 1867;

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 31 January 1868

6.

The London Gazette, 16 August 1872 p.3727

7. Western Morning News, 9 November 1876, 1 September 1877

8. Western Morning News, Western Times, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, Western Daily Mercury, various dates between September 1872 and June 1874.

9. Letter from Cyrus W. Field to A. van der Linde, Brooklyn, 11 June 1888. Private collection.

10. Gloucester Citizen, 23 October 1891

11. Gloucester Journal, 1 August 1908

Other information from UK census data, marriage records, death registers, and probate records, as noted in the text.

Return to the Atlantic Cables index page |