Introduction:

In the summer of 1865, seven years after the failure of the 1858 cable,

another attempt was made to lay a cable between Ireland and Newfoundland using

Brunel’s Great Eastern. As well as the cable engineers and crew, the ship carried a number of passengers as guests of the cable company, including John C. Deane, who

kept a diary of the expedition; journalist William H.

Russell and artist Robert Dudley, the official chroniclers; and another artist, Henry O’Neil.

O’Neil, a historical painter who sailed on Great Eastern hoping to return with a scene of the cable laying, instead wrote a story of the voyage from an artist’s viewpoint, which was published in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine after the return of the expedition.

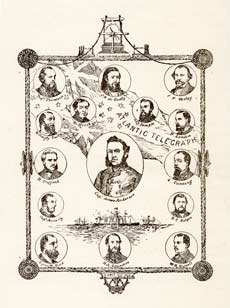

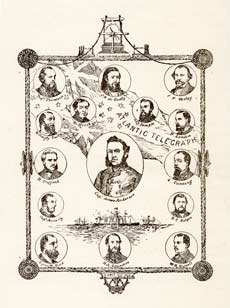

O’Neil sketched the main participants in the 1865 Atlantic cable expedition for the on-board newspaper (illustration below), which he also edited, and this drawing was later reproduced in Willoughby Smith’s book The Rise and Extension of Submarine Telegraphy. Smith writes:

“During the voyage Mr H. O’Neil, A.R.A. issued from time to time, though far too seldom, The Atlantic Telegraph, a paper which certainly touched a chord of humour that would otherwise have remained mute amid the cares and anxieties felt by all.”

1865 cover by Henry O’Neil

for the ship’s newspaper

The Atlantic Telegraph |

Five issues of The Atlantic Telegraph were published on board Great Eastern during the course of the 1865 expedition, and O'Neil edited five more shipboard publications in 1866 when he accompanied the expedition which successfully laid the Atlantic Cable. That year he again recorded his experiences for later publication – written in the form of a letter to his friend “Marcus”, the story was published in London Society. An Illustrated Magazine Of Light And Amusing Literature For The Hours Of Relaxation, Volume XI. Although the article was signed “Henry Plantagenet Dynamometer”, it was clearly written by O’Neil.

Charles Bright, in his 1898 book Submarine Telegraphs, notes:

Detailed and stirring accounts of the events of this [1865] expedition also appeared subsequently in Blackwood’s Magazine, in Cornhill, and in Macmillan’s. The former was written by Mr Henry O’Neil, A.R.A., and the latter by Mr John C. Deane, both of whom were eye-witnesses aboard the “Great Eastern.” Mr O’Neil also brought out an illustrated comic journal during this and the following expedition, issued at periodic intervals, which was a source of much amusement to those who had time for perusing.

Still more was an “extravaganza” —written by Nicholas Woods and J.C. Parkinson—on the subject, performed on board on the completion of all the work in 1866. Both these were afterwards published in booklet form, and are much treasured by the parties caricatured therein.

Henry O’Neil’s articles from the 1865 and 1866 voyages are reproduced below. |

| --Bill Burns |

1865 Expedition

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine

October 1865

In writing this simple narrative of the voyage of the Great Eastern, it is not my intention to enter unnecessarily into any scientific details, either as regards the vessel itself, the Cable, or the machinery used for paying it out, or picking it up, and this for two reasons: Firstly, because these details have already been placed fully before the public in other forms; and, secondly, were I to do so, I feel that the blunders I should make would probably be so numerous that my statements would be comparatively worthless.

It may then be asked, considering that the subject has already been so ably treated by Dr. Russell, what object can I have in view in putting another version before the public? This question is easily answered. The narrative of any event, and especially of this expedition, naturally takes its tone from the temper of the writer, and its character will be mainly influenced by his profession and pursuits. So there may be the purely historical description —there may be the political, the philosophical, the scientific, the poetical, dramatic, or the artistic description—and it is in the spirit of the last that I venture to address my readers. As an artist, I felt deeply grateful to the Directors of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company for the permission, so courteously accorded me, to join the expedition; for I fondly hoped, and fully believed, that, both during the voyage, and more especially at its successful termination at Newfoundland, some incidents would occur which would form the materials for an interesting picture; so that I, too, might have a share, however humble, in transmitting to posterity the success of so noble an undertaking.

With the temporary failure of the present expedition this hope has not finally vanished; for I still trust that, through the kindness of the Directors, the chief object I then had in view may at some no distant period be fully attained. In the mean time, I hope that the notes I have collected during the voyage, and which I now lay before the public, may not be wholly devoid of interest, even though they do not at present appear on canvas.

At noon on Saturday, July 16th [ship’s time is used throughout this article], the Great Eastern left her moorings at the Nore, and, guided by the Government steamer Porcupine, proceeded on her voyage amidst the most enthusiastic cheers from the crews and passengers of the various yachts around her. Her course was down a new channel called the “Bullock,” which had been sounded and buoyed by the Admiralty. One of the most exciting scenes I ever witnessed was the heaving-up of the anchor, each link of the chain attached weighing over seventy pounds; and nothing could give a better conception of the size of the vessel than the power required in performing that operation. Round the capstan revolved sixty men, with a like number in each of the two lower decks, whose combined efforts were unavailing at times to stir the anchor, in spite of the animated exhortations of Mr. Halpin, the chief officer, and the lively strains of a young fiddler, who, perched on the capstan, played such music as sailors love to hear. At the first sound, however, of the tune, “Slap bang, here we are again!” the men made a determined effort, and, all joining in the lively chorus heart and voice, they succeeded in overcoming the resistance offered; but it was not till after many repetitions of the same invigorating air that the anchor was finally brought up.

Our progress was at first so painfully slow that some grave doubts arose as to whether the vessel could ever attain such a speed as six knots an hour. During her course down Bullock Channel, and even as far as Dover, so long as daylight lasted, ever and anon an excursion steamer or sailing-boat came alongside filled with passengers, who, in spite of the languor of sea-sickness, testified their good wishes for our success by cheering with hearty goodwill. At 4.15 P.M. the Porcupine, having hoisted up a white flag at her mizzen bearing the words, “God speed you,” turned slowly round, and, on passing the Great Eastern, gave a ringing cheer, which was answered by deafening shouts on the part of our men, and then alone we proceeded on our eventful voyage.

Descending from the bridge to look about me, my first impression gave me the notion of a decent-sized village. Around me were blacksmiths’ forges, carpenters’ shops, all resounding with the hum Of busy workers. On looking at the live-stock on board, we seemed like a large community seeking another home, taking everything necessary for a permanent settlement) with the exception of the emigrant’s chief blessing—namely, a wife: for I need scarcely say that none of the fair sex accompanied the expedition. We numbered nearly five hundred men in all, to supply whose wants there were twelve oxen, one cow, one hundred and twenty sheep, twenty fine Hampshire pigs, and innumerable geese, ducks, and fowls, and all these independently of hundredweights of fresh and preserved meats. Nor must I forget to include a black cat and a jackdaw, who often during the voyage would perch for hours on the top of the dynamometer watching the paying-out of the Cable, apparently, with self-satisfied complacency.

Some idea of the size of the vessel may be obtained by stating that the length of the walk on deck, which we named Regent Street, was exactly one-eighth of a mile; and here daily would the energetic Mr. Cyrus Field take his exercise before breakfast and dinner, taking such hasty strides that no one on board could keep up with him.—Or look at the steerage. Below the deck aft is a spacious room, in which four large wheels are placed in a line from stem to stern, at each of which are two men: though there are two compasses before the foremost wheel, the men steer entirely by the brass finger of a dial, whose motions are guided by the chief steersman, who stands at the wheel in the centre of the ship, which notwithstanding all prognostications to the contrary, answers readily to the helm, though going at a speed of only four knots per hour.

A boatswain on board who, with ten men, had charge of the vessel during the winter, describing her size and solitude, said to me, “Sir, a man might have lain dead in some cabin astern for a whole week before we at the bow would know of it.” And I can easily believe it. I have explored the vessel as much as most men on board; I have wandered through long dark passages at moments illumed by the fierce and sudden blame of an open furnace—nay, I have descended to the very kelson—and yet I know that there are many places from which I should find it difficult to emerge again into light. In my survey I noticed particularly that the names of many streets, alleys, and taverns in the neighbourhood of the docks were painted on various parts of the lower decks, showing how a sailor loves to bear with him a memory of his favourite and familiar localities.

The speed of the vessel increased gradually during her course down the Channel from four to five, and ultimately to six knots per hour, which later rate she steadily maintained throughout the run to Valentia, even with the extra weight she had to tug through the waters during the latter half of the voyage. At 5.30 A.M. on Sunday we were off Beachy Head, and at 11 Captain Anderson read prayers in the dining saloon, which was by no means crowded, though more than two hundred men attended service. Early on Monday morning Plymouth was reached, and we made the Lizard Point at noon, and there we noticed ahead of us a screw steamer labouring violently, and evidently determined to overhaul us. She proved to be the Caroline, which left the Thames several days before us, bound for Valentia, and having the shore-end of the Cable on board. We had fully expected to find her at her destination, but she was so heavily weighted that the slightest breeze was too much for her; so, running for shelter into Falmouth, she there awaited our coming up. A strong new line being sent astern, we immediately took the helpless vessel in tow, and had every reason to congratulate ourselves that we were not on board of her. Her fearful rolling and pitching, however annoying to her inmates, were to us, sitting on the paddle-boxes of our motionless ark, highly interesting, exciting, and even amusing. It was like viewing a looming shipwreck from the comfortable boxes of a theatre, with the additional advantage of knowing that the scene, with all its accessories, was sternly real. Throughout the night the wind blew hard, she held on bravely, her crew, whatever apprehension her wretched state gave rise to, knowing well that without our assistance, there would be probably such a delay as might prove fatal to the undertaking. Nothing occurred until we had passed the Skilligs, two islands about eight miles distant from Valentia, when the rope gave way just over the bow of the Caroline, and she parted from us; but with a fair wind, and being so near her destination, we had no further fears for her safety. At the same time, about 6 A.M. on Wednesday the 19th of July, we came up with the Terrible and the Sphinx, the two war steamers appointed to convoy the Great Eastern across the Atlantic.

As the laying of the shore-end of the Cable would necessarily occupy some days, Captain Anderson thought it prudent to seek safer quarters than the immediate neighbourhood afforded; so, sending Mr. Canning, the chief engineer, on shore to superintend the laying of the shore-end, we turned south and steered for Bantry Bay, where we anchored at 4 P.M. towards the east end of Bear Haven there to await further orders. Immediately on our arrival we were invaded by a fleet of boats containing the whole commercial population of Bear Island and the adjacent mainland. From the rough appearance of the natives, and the rude simplicity of their naval architecture, we might easily imagine ourselves in the neighbourhood of some country not often visited by civilised nations. Like ants climbing up the heaven-sent carcass of a huge elephant, so does this human swarm clamber up the gangway with frantic yells and shouts; and, utterly regardless of the danger of falling into the sea, they push each other wildly in their eager endeavours to be the first on board. The deck once gained, they establish a position in the fairest portion of the ship, from which it were vain to try and remove them; and there displaying their wares, they open a profitable intercourse (at least on one side) with our silly crew. We all know how lavishly a sailor spends his money, on useful things if possible, but if such be not obtainable, then on anything. Here have we been scarcely five days at sea, and yet, judging from the eagerness with which our men part with their money, one would imagine that they had just arrived after a six months’ cruise at least. And what things they purchase! One man carries off in triumph a goose, which, when plucked, would hardly suffice for the dinner of even a moderate eater, and yet he liberally invites two or three of his comrades to share his Sunday’s repast, when he hopes to enjoy his cherished delicacy, stuffed, as he promises them, with heaps of onions. Another purchases a pair of woollen stockings, which seem better adapted for grating nutmegs than for comfort. Hundredweights of bad butter and rocky cheese—gallons of odious stuff called buttermilk—salt-fish of three years’ pickle—scores of eggs—mountains of bread, of which they can get what they like on board—clumsy pipes—poultry, dead and alive—lines to catch cod-fish in Newfoundland (the latter bought also by the gentlemen)—everything is purchased, and at prices, too, far exceeding those usual in our not over-cheap metropolis. As to the mere sightseers and idlers on deck, whatever impression the vast ship made on them it would be difficult to guess, their admiration being exclusively bestowed on our black pigs. I particularly observed one gentleman, dressed in remnants of varied hue and material, whose contemplation of those animals produced a mixed feeling of delight and regret. Daily he came on board, never moving from the spot they occupied (the painter’s shop), inhaling the cherished odour, and ever making earnest but fruitless attempts to obtain one from the purser, in exchange for a huge white pig he left in his boat below. Nor must I forget the noble patriotism of one visitor, evidently a merchant of great standing in the country, who inquired if the ship wanted coaling, offering, in that case, to place fifty tons at our disposal. And most amusing was his expression of astonishment and unbelief when he was informed that the quantity he offered would scarcely suffice for five hours’ consumption. When the market flagged, either through the absorption of the supply or the weakness of the demand, our sailors invited the natives to a Terpsichorean contest; so the fiddler was brought on deck, and after much coyness on the part of the performers, several highly characteristic, but, in my opinion, very monotonous and ungraceful figures were executed on both sides. At sunset, after repeated orders, and with much trouble, our noisy visitors left the ship, their departure being attended with the same frightful yells and shouts that had graced their arrival.

On Thursday morning, the weather being fine, Captain Anderson proposed making the ascent of Hungry Hill, a mountain adjacent, whose summit reaches to the respectable height of 2050 feet; it being his custom, wherever he anchored, to select the highest spot of land in the neighbourhood, and to ascend it, in order to learn the nature of the country around. Several of us joined him in this by no means formidable-looking excursion, though, before we were half-way up, many of us regretted that we had not remained with those keen sportsmen below, who spent the day in vainly seeking some feathered, or indeed any object on which to exercise their skill. After a tedious ascent, we at last reached the summit, but, as is usually the case, only to find ourselves enveloped in a dense fog. Before we descended, however, it cleared off for a few moments, enabling us to get a hasty glimpse of the scenery around, whilst far in the distance we descried the Terrible and the Sphinx entering the haven by the narrow channel at the west end. This latter fact was the signal for a hurried and over-precipitous descent, from the tumbles met with in which some of us did not recover for many days.

Throughout Thursday and Friday the ship was visited by numbers of the neighbouring gentry, and the market was kept up as usual, though the arrival of the two men-of-war relieved us from a little of the pressure. On Friday evening, Captain Napier of the Terrible, and Captain Hamilton of the Sphinx, with all the officers of both vessels, joined us at dinner. Amongst the latter were two intelligent young Danes, whose talk was naturally about our beloved Princess, and the shameful spoliation of their country; and certainly it would be difficult to find two themes better calculated to awaken a Briton’s loyal enthusiasm, or to arouse his fierce indignation.

In spite of the lovely scenery around, we were getting tired of our pleasant inactivity, and were anxious to leave our present moorings. Sorely grieved, too, was Captain Anderson at the delay caused by the late arrival of the Caroline, for well he knew that the time was approaching when the weather could not be depended on for two days together. It was, therefore, with intense satisfaction that we hailed the arrival of a coast-guardsman from Valentia, who, coming overland, reached our ship on Saturday at 11 P.M., bringing the welcome intelligence that the Caroline had commenced laying the shore-end of the Cable (about twenty-seven miles in length,) and that the operation would be completed early on the following morning; so, getting up steam as quickly as possible, we weighed anchor at 2 A.M. on Sunday, July 23d, and, followed by the Terrible and the Sphinx, proceeded to the spot where the splice was to be effected. At 10.30 we came up with the Caroline, and shortly after the Hawk, a fine steamer belonging to the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, arrived, having on board a distinguished party, including Sir Robert Peel, the Knight of Kerry, Lord John Hay, Captain Hamilton, a director of the Atlantic Telegraph Company, and many other gentlemen connected with the undertaking. There were also some ladies on board, who were sadly disappointed at not being able to visit the ship,—a task which, owing to the roughness of the sea, even the gentlemen could not accomplish without a wetting. Here Mr. Canning rejoined us, accompanied by Dr. W.H. Russell, Mr. Deane, Mr. Temple, and others. The paddle-box boats of the Sphinx having taken the end of our Cable on board the Caroline, the splice with the shore-end was successfully effected at 5.30 P.M.; and the last visitor having left our ship, amidst the firing of guns and loud cheers from all the five vessels, we commenced paying out the Cable from the aft tank at a speed of about four knots per hour.

And now, before proceeding further with my narrative, I think it expedient to explain as briefly as possible the nature of the operations to be performed, and also the means to be employed for carrying them out, in order that I may, if I can, make the subsequent events thoroughly intelligible to the reader.

The Cable, two thousand three hundred miles in length, was coiled in three tanks; one at the stern (I take them in the order used), the second in the fore-part, and the third in the middle of the vessel. The first contained about 840 miles of Cable, the second about 640 miles, and the remainder, together with the shore-end for Newfoundland, was coiled in the middle tank. The ends of these separate coils were kept joined, and the transfer from one tank to another was performed with the greatest ease. From the fore-tank, a trough, with revolving wheels placed at certain distances to prevent too great friction, extended to the paying-out machinery at the stern, whilst from the other tanks smaller troughs led to the main artery. The paying-out machinery, as I have said, is placed at the stern, and is, perhaps, I the most perfect thing of its kind that has ever been constructed, not a hitch occurring in its working throughout the voyage. It consists of a large wheel, round which the Cable makes two turns, and then, passing out, it glides over a succession of smaller wheels, over which others are placed, acting as breakers to prevent it paying out too quickly. Between the last wheel of this machine and the one immediately over the stern of the vessel the dynamometer is placed. This is an instrument for calculating the strain to which the Cable is subjected in its progress. Through the upright grooves of an iron frame, a wheel, UNDER which the cable passes, slides according to the varying strain, the amount being indicated by figures on the side of the frame. When it is necessary to pick up the Cable, a wire rope is passed from the wheel at the bow, and thence outside the vessel to the stern, where it is brought up and fastened securely to the Cable, which is then cut, and the whole dropping into the sea, the rope is hauled in at the bow until the Cable is brought on board and fixed to the picking-up machinery, which is worked by a small steam-engine, and between this machine and the bow-wheel is another dynamometer. Lastly, there are rope-stoppers used to retard the progress of the Cable, or the wire rope when in use; these are made of untwisted hemp rope of great thickness, and are twined two or three times round the cable or rope, and the ends being pulled down by the men, the resistance they give is very effectual. To conclude this explanation—in order to ascertain the perfect continuity of the electric current, signals were continually passed along the whole Cable to Valentia, and vice versa, and these tests were made every ten or fifteen minutes throughout the day and night.

And now to resume my narrative. The paying-out of the Cable progressed satisfactorily, the speed increasing to six knots per hour, beyond which rate it was not thought advisable to proceed. Things looked bright indeed; and as regards the elements, no expedition could have started under more favorable auspices. The cloudless afternoon had given place to a real summer evening, and watching from the paddle-boxes the magnificent sunset (our first in the broad Atlantic) under the soothing influence of our pipes, we banished all fear and anxiety, already speculating with too sanguine confidence as to the time we should reach Newfoundland; and when at last we retired to rest, not one of us dreamed of impending disaster.

At 4.20 A.M. on the following morning I was aroused from sleep by the booming report of one of our guns—that being a preconcerted signal for the men-of-war to stop. I hurried on deck, and to my dismay learned that the signalling was imperfect, indicating that some accident had happened to the Cable. Fresh tests were applied over and over again, but ever with the same mortifying result. The communication with shore, however, not being wholly stopped, though it was impossible to say how soon that might occur, orders were given to send out the Hawk to our assistance. In the mean time the Cable had been cut, and, being transferred to the machinery at the bow, we proceeded to pick it up at the slow rate of one mile per hour. Before this latter operation, however, could be begun, we had paid out twelve miles or more; so that supposing, as it was conjectured, the faulty portion of the Cable had passed overboard at the time of the discovery, it would require twelve hours to bring it to light. When six miles of Cable had been drawn up, it was cut, and tested to see if the defect was on board; but such not being the case, we resumed the tedious process of picking up. At 5.30 A.M. on Tuesday the Hawk arrived. By this time ten miles of Cable had been hauled in, and again it was cut and tested, but with the same result as before. Very early it was discovered that the steam-power of the picking-up machinery was defective; and Mr. Canning, the chief engineer, attempted to remedy this defect by bringing into service a small locomotive on board. A consultation having then taken place between the chief engineers and electricians, it was thought advisable to return to the spot where the splice with the shore-end had been made; but Mr. Canning was anxious to see the result of his additional machinery; so having picked up about two hundred fathoms more of the Cable, to the delight of all, the faulty part was brought on board. On examination it was found that a piece of the iron wire, of which the outer covering of the Cable is partly made, had penetrated the gutta-percha, thus destroying the perfect insulation of the copper wires. Some suspicion arose of foul play, such an instance having occurred some years ago in laying a cable in the North Sea, a crime which was only brought to light two years after by the confession of the culprit, who declared that he had been offered one thousand pounds if he succeeded in his diabolical attempt.

At 1 P.M., the splice being made, we again proceeded on our course, but not for long. Half an hour had scarcely elapsed, when, to the surprise and dismay of all, a fresh fault was announced. This time the disaster looked serious, for all communication with the shore was totally lost. Patiently we watched the application of continual tests, the very mention of picking up producing a feeling of gloom, and the mere sight of the machine becoming hateful. When at last we were about to have resort to it, suddenly the signals were again perfect; and soon after, with much laughter at our fears, we learned that the cause of all our anxiety and despair was the removal of an instrument at Valentia, for some purpose beet known to those on shore; and then resuming the satisfactory process of paying out of the Cable, with thankful and merry hearts we again proceeded on our voyage.

At 8 A.M. on Wednesday, July 26th, we desired the Sphinx (the only vessel having the proper apparatus) to take soundings. Having stopped for that purpose, she was unable to overtake us. Gradually she became less distinct, and on Friday morning we lost sight of her for ever; and it was supposed that she passed us in a foggy night whilst we were picking up the second fault. From this time up to Saturday the 29th no fresh announcement of disaster interfered with the proper attention to our meals, or destroyed our equanimity; and I take this seasonable opportunity to say a few words about the company on board.

And first, as in duty bound, let me mention Captain Anderson of the China, one of the Cunard steamers, specially selected on account of his great experience for carrying out this arduous enterprise. Of him I may truly say that I never met with a nobler specimen of a race of men whom, from my earliest youth, I have ever regarded with the utmost respect and admiration—brave, yet God-fearing; stern on duty, yet gentle at other times; and of such skill that it is not surprising his reputation as a commander should be no high. Then follow two gentlemen on whose ability the success of the undertaking mainly depended—namely, Messrs. Canning and Clifford, the chief Engineers, whose characters will be best developed in the events that occurred. Next follow Messrs. de Sauty and Saunders, the chief Electricians of the expedition. There is Mr. Gooch, now M.P. for Cricklade, who as a director of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, and also as a director and chief proprietor of the Great Eastern, necessarily leads a most anxious life; and Mr. Cyrus Field, the pioneer of Atlantic enterprise, full of hope and confidence, and never betraying anxiety or despair even at the most serious disaster—a man whose restless energy is best shown in his spare yet strong frame, as if his daily food but served for the development of schemes for the benefit of mankind in general and the profit of individuals in particular, every stoppage in our progress being marked by the issue of a fresh prospectus, each showing an increase of dividend as the certain result of confiding speculation—and I say all honor to him for his unswerving resolution to complete-that great work for the success of which he has toiled so long and so earnestly.

Then we have Professor Thomson and Mr. Varley, two eminent electricians sent out by the Atlantic Telegraph Company to draw up a report of the voyage, but who have no authority to interfere in the management of the expedition: most learned men are they; so precise, that a difference in their respective calculations of even a millionth part of a decimal involves a long and animated yet perfectly amicable discussion. A valuable man, too, is Captain Moriarty, R.N., whose services cannot be too highly acknowledged, his skill and precision in taking observations being of the greatest benefit. No chance of escape has the coy sun; let him but peer forth an instant, and Moriarty’s keen and quick eye snatches the information required. There are also in our saloon Messrs. London, Temple, and Willoughby Smith, all connected with the expedition; nor must I forget M. Despecher, a French gentleman who has witnessed the laying of many a marine telegraph cable; a great traveller, and therefore more free from prejudice than some of his countrymen.

There is Dr. Ward and his son, who have plenty of work to do, and so has Mr. Deane, ever busy taking notes for a history of the expedition, for which the genial and industrious Mr. Dudley is preparing pictorial illustrations; and last, not least, the well-known Dr. Russell, who not only supplies the literary portion of the aforesaid work, but who also has to furnish an elaborate report of the voyage for the Company to forward to the press: an excellent companion is he on a long voyage, ever chatty and cheerful, and full of anecdotes and information picked up in every quarter of the globe. It is said that Caesar, Napoleon, and I believe, our own Wellington, could write despatches and give verbal orders at the same time; but in this respect Russell beats them all. I have seen him correct the proof sheets of a newspaper of which he is the editor, enter into the general conversation, and, moreover, play a rubber of whist, all at once, though I fear with some detriment to his partner’s interests in the latter operation; his two sons, Willie and Johnny, accompanying him, looking forward with delight to catching a cod-fish in Newfoundland.

There are also many young gentlemen in the other saloon who accompany the expedition for the purpose of acquiring experience as engineers or electricians, amongst whom are Mr. Gooch’s son, Messrs. Crampton, jun., and Trench, and a most ingenious little mechanician, M. Schafer, whose good temper was proof against all the practical jokes played on him: a most useful member of the community was he, repairing with great skill and readiness any article broken on board, from a watch to a meerschaum pipe. His last mechanical exploit was the fashioning of a small knife from a piece of the iron wire of the cable, the blade of which was only three-tenths of an inch in length, and warranted to cut. My list would not be complete were I to omit Mr. Halpin, the chief officer; a quondam blockade-runner, full of Southern proclivities, and with a hearty dislike of the stars and stripes, prolific of marvellous sea-stories, every inch (and many has he) a sailor, and a great favourite with all.

How smoothly does the Great Leviathan glide through the water! So quietly work the ponderous engines, and with so little vibration, that, except for the smoke (of which more anon), you could scarcely believe you were in a steam-vessel. But alas! “surgit amari aliquid.” As in a community of workmen, those who do the least work make the most noise, so in this huge factory of machinery there is a small auxiliary engine, very properly called the “Donkey,” which makes an incessant noise, with but little intermission, during the whole twenty-four hours. My feelings were too hostile to allow me to make any inquiries as to the nature of the functions performed by my tormentor (something in the pumping line, I believe), but if I might judge by the noise, I should say that not only had it to propel the vessel, but also to perform all the work done on board by machinery. With great tact, too, this little monster has been so placed that the inmates of the chief saloon shall have the most practical experience of its obtrusive activity, as if to remind them that life even on board the Great Eastern is not wholly a bed of roses—truly a moral doctrine, but very trite and utterly superfluous amidst circumstances that serve to keep it ever fresh in remembrance. Moreover, it is useless to try and escape the annoyance by changing your cabin, for, like the ghost of Hamlet’s father, it is by nature ubiquitous, and wherever you wander, there also shall its rap-rap be heard. Yet, in spite of this little nuisance, what life can be compared to a life at sea, especially in such a good ship, where there is little or no chance of ever being prostrated by seasickness? No doubt it has its drawbacks, but what existence is free from them? True, you cannot wander in green lanes, nor feast the eye on fresh verdure and the varied hues of “rain-awakened” flowers, but in no state can you be more independent of those petty cares which cloud the sunshine of the mere dwellers on earth. You are free from the extortion of cabmen and the inconsiderate rush of a city’s mob. There are no letters to write, no calls to make or receive, and no bills to pay. The tax-gatherer, the poor-rate collector, and all the other blessings of civilised life, are unknown. In all security you walk abroad, and in the darkest hour of night dismiss all fears of pickpockets and garotters. You keep up no wife for your late return, and the latchkey is laid aside. Last, and chief blessing of all, money, without which you cannot move an inch on shore, is at sea a mere drug, and not of the slightest use or consideration.

Perched aloft in the rigging, I was wholly absorbed in these pleasing reflections, and, with pipe in mouth, was enjoying the scene around me, engaged in no more serious occupation than watching the baffled waves break against the vessel in imbecile attempts to disturb its equilibrium, when I was suddenly aroused from my dream of sweet content by a sound of suppressed laughter from below, whilst, at the same time, I experienced a curious sensation, indicating a want of freedom in my lower limbs. Looking down, I saw a sea of grinning faces beneath, and at my feet stood a good-humoured sailor, holding the ends of a cord, with which he had lashed me to the rigging, who said, “Please your honour, pay your footing!” What could I do? Though, like Don Juan, by nature choleric and sudden, and sorely vexed at his abrupt overthrow of my speculations, I could not but join in the laugh against me, and comply with the request so courteously made. So, graciously dropping a coin in my highwayman’s hats I received from him a certificate in satisfaction of all future demands, and, moreover, entitling the bearer henceforth to the free and undisturbed use of spar or rigging, and then I was speedily released from my ludicrous and over-conspicuous position; nor do I intend to scratch out a word I have said, for, with this trifling exception, nothing occurred during the voyage to upset my theory of the utter valuelessness of money when at sea.

And now a word or two about our amusements, of which, if I may judge by the alacrity shown in attending the summons of the various bells, those connected with the culinary department are by no means of the least importance. At 8 A.M. we sit down to a substantial breakfast, which would be perfect but for the absence of milk. True, our cow is dead, but as she never yielded a cupful of that beverage, the queer quality of the article supplied must not be laid to the charge of the poor beast. The pipe and cigar follow immediately, and then till luncheon we either pass our time in watching events above or in literary or artistic occupations below, the latter, however, attended with some difficulty. The saloon of a vessel, freighted with nearly five hundred human beings, is ill adapted for serious pursuits, and there are defects in that of the Great Eastern, as arranged for this voyage, which are not apparent in other ships, though I acknowledge that in one point she beats every vessel afloat, and that is her extreme steadiness of motion, even in a stiff breeze. I have heard that great worker, Anthony Trollope, declare that on board of the Cunard steamers he could write as well and as indefatigably as at home, but I doubt if even he could do so in the saloon of the Great Eastern. Independently of the curiosity and anxiety naturally aroused by the knowledge of what is going on above, there is noise enough below to wake the very dead. The under saloon has been turned into a carpenter’s shop and a general receptacle for timber and other ship-stores, and it would, seem as if it was the sole duty of some half-a-dozen noisy men (relieved at times by half-a-dozen noisier men) to be continually lowering or lifting huge logs of wood, which bump about, damaging the gilding and tearing the pretty paper, to the evident discomfort and horror of Mr. Gooch, and also destroying the repose of those who are either writing or reading, or doing that for which reading is so good a cloak-namely, sleeping. In vain M. Despecher sets himself down to get through the two tasks he was resolved on performing during the voyage. The careful study of ‘La Vie de Jules César,’ and the ‘Traité sur la Télégraphie’ is utterly incompatible with the incessant “Yow, ow, ows” of the men, and the sudden and sharp calls made on his attention by the logs of wood—so, slamming violently the pages of his beloved books, he flies to they piano, and from the lively strains of the “Guards’ Waltz” strives to produce a counter-irritation. How Professor Thomson and Mr. Varley can fill sheet after sheet with abstruse theorems and problems illustrated by a whole army of letters commanded by X, Y, Z, is to me a wonder—and I can only conclude that, their occupations requiring more head than heart, they are not alive to the disturbing elements around them; but before deciding this point I should like to know what Mr. Babbage would feel under the circumstances.

A few hours before dinner are occupied in pacing the deck and inhaling the sea-breezes impregnated with smoke, which is extremely pertinacious in its attacks. Carefully avoiding the constant reek of the four funnels (thank necessity, the fifth has made way for a tank), you are met on all sides by the obnoxious vapours of the innumerable galley chimneys, and you get out of the way of these only to encounter the blacksmith’s blast or the still fouler breath of the small locomotive. To those who seek exercise combined with amusement, the games of shovel-board and quoits offer every advantage. At times we have music, Dr. Ward being an excellent performer on the violin, and M. Despecher a decent one on the piano, though, like most of his countrymen, he has no great love for the classic masters. At 5.30, that glorious “tocsin of the soul, the dinner-bell,” calls us down to the absorption of a sumptuous meal enriched by wines of excellent quality. Indeed, in these matters the Directors have shown a most praiseworthy liberality—so much so, that a joker on board, alluding to the title of the Company, said, “As regards ‘Construction’ I know nothing, but I can safely assert that it is a most excellent ‘Maintenance’ Company.” No wonder that Dr. Ward has so much to do, or that his patient son is worn with fatigue in dispensing medicine in the various cabins. However abstemious we may be on shore, the appetite at sea never seems satisfied. People—I speak also of myself—who when at home found the greatest difficulty in consuming a few inches of dry toast at breakfast, can and do here actually dispose of two or three muttonchops, a plate of broiled ham and eggs, and a whole rackful of toast. Nor does this suffice till dinner, the luncheon-bell being eagerly attended to. Amusing is it to see these delicate creatures daily sipping sherry and bitters at five, as if their poor appetites required any stimulant. As to the dinner, I say nothing. Considering that the bill of fare contains about twenty items, natural curiosity, even without hunger, would be a sufficient reason for not starving. At tea, like children, they enjoy their toast and marmalade, and make no objection to biscuits and cheese at ten; and verily I believe they would not fail to attend were there even an additional meal or two added to the already too frequent repasts of the day. To conclude my list of amusements; the evening is spent at whist, chess, or other games, and early to bed is the order of the night.

To return to my narrative. On Saturday, July 29th, at 1 P.M., to the sudden discomfiture of our hopes, another fault was announced, and of a far more serious nature than the first. There was no delay this time. As soon as possible the vessel was stopped, and the Cable cut and transferred to the bow; but again, owing to the want of steam, two miles or more had been paid out before the machine was ready to pick up the submerged portion. It was the unanimous opinion of the electricians that the fault was only two miles distant (it being, in fact, on board when discovered); and exactly that amount of Cable having been hauled in, the defective part was brought to light. Again had a piece of the same wire penetrated the Cable; this time right through, touching the copper wire, and destroying the continuity of the electric current. The affair looked black indeed. At 7 P.M., the splice being made, another mishap occurred in transferring the Cable to the stern. At all times this operation is attended with some danger, owing to the length of the ship and the many obstructions to be avoided; and, if possible, I cannot but think that it would be safer to have the picking-up machinery placed aft, though, no doubt, there would then be danger of the Cable getting entangled with the screw; add to which, the difficulty of steering so large a vessel going astern, which would in that case have to be done whenever the picking-up process was resorted to. This accident being soon repaired, once more we anxiously resumed our course.

Mr. Canning, having cut off the piece of Cable which had the broken wire through it, called the men together, and one by one asked their opinion on the matter. Almost unanimously they declared that the disaster could not have been the result of accident; and such was their indignation, that, supposing their verdict to be correct, the culprit, if discovered, would have met with no mercy at their hands Still, without ascribing the disasters which had occurred to malice it was determined by Messrs. Canning and Clifford that every possible precaution should be taken and for this purpose they requested the inmates of the saloon to take their watch by turn in the tank day and night. This was readily acceded to, the men even acquiescing in the arrangement, though with regret, Certainly it was painful to doubt their honesty, especially as so many of them had been for years in Mr. Canning’s service; but this precaution was as useful to them as to him, for when the peculiar nature of the accidents be considered, taking into account their similarity, together with the conclusion arrived at by the men themselves, with this startling fact, moreover, that they all occurred during the same watch; and knowing, as I have said, that such had occurred before, it was difficult to avoid the suspicion of foul play, and that some one man, either through malice or hope of gain, had been the cause of these misfortunes. It must be said, however, that Captain Anderson, after much reflection, cast aside all idea of mischief, believing that accident often produces stranger coincidences than .can be effected by design; and without expressing any opinion on the matter, I shall be sincerely glad if the Directors, after thoroughly sifting this unfortunate business, arrive at a similar conclusion.

At 3.30 A.M., July 31st, the last coil of the Cable in the aft tank being paid out, the vessel’s progress was stayed for a few moments, and the shifting to the fore tank was performed with the greatest ease. All went on smoothly until Wednesday, August 2d. During this time I had taken my watch in the tank twice without observing anything in the least degree suspicious; nor was I sorry to have had the opportunity of seeing with what perfect ease and celerity the Cable uncoiled itself and passed upwards. At 7 A.M., Mr. Cyrus Field, keenest of watchmen, being in the tank, the last fault occurred, and, strange to say, with the same gang of men in the tank as were present at all the previous disasters. We had now run 1062 miles from Valentia; having only 604 miles more to reach Newfoundland, 300 of which were comparatively shallow, where all danger of failure in picking up the Cable would vanish. By this time we had become resigned, and even callous, looking on these misfortunes as only causing a temporary delay.

This being our crowning disaster, and the cause of all our future operations, I wish to describe it with a little more minuteness. At 10.30 A.M., in 1at. 51°.25 N., long. 390.1 W., the Cable having been cut and transferred to the bow, the picking-up machine was started, and had hauled in about two miles when the boiler of the capstan engine became short of steam, and whilst waiting for a fresh supply the wind suddenly changed. In attempting to get the ship’s head to wind she drove over the Cable, causing it to pass under her fore-poop, and foul of the hawse-pipe at the stem on the port-bow. The engines were immediately reversed, and every endeavour was made to get the ship’s head round, but without success. As the Cable was being chafed, a stopper attached to a Manilla rope was put on, and line veered away until the Cable was clear of the hawse-pipes, when it led away round to the starboard. We were hauling in a few revolutions in order to get the chafed parts on board as quickly as possible, when, at twenty-five feet from the bow, with a sharp snap the CABLE BROKE, and, rushing through the stoppers to which the men held on bravely was sucked into the sea and lost—perhaps for ever.

All the power of language is weak, indeed, to convey the effect produced by this disaster. The shock was so sudden and unexpected that we could not immediately realise our position. For an instant it paralysed us; we looked at each other, but spoke not: yet from out the very silence that fell on us there breathed a mute questioning, as if the tale needed repetition to ensure belief—for the announcement was made in a low whisper, as if the calamity were too great to be uttered aloud, and in the hope that some partial relief might be obtained by not spreading the report too quickly. Then for a while it changed the nature of all, in respect of moody peevishness, reducing us to a uniform level. Our very occupations seemed hateful; the piano was shut; the mere mention of whist was met by a reproving shake of the head; and the editor of a newspaper, published weekly on board, refused to issue the looked-for journal, as if to say “Whilst there is so much going on to excite your hopes and fears, what need have you of amusement I nor are you in a proper temper to receive it, even if offered.” For a moment Captain Anderson lost his ever-hopeful smile, and Messrs. Canning and Clifford slightly forgot their usual courtesy. Mr. Gooch went below, vainly attempting, through sleep, to obtain oblivion, and Mr. Field locked himself in his cabin to draw up a fresh prospectus. Mr. Halpin uttered more than his usual allowance of oaths; whilst Mr. de Sauty, his occupation gone, fetched his largest pipe, and, standing with his back against the doors of his electric office, with hands plunged deeply into his pockets, smoked fiercely, as if to conceal his anxiety behind the densest cloud. Even the two young Russells lost their usual spirits—and no wonder, for failure, to them, meant a speedy return to school and all its restraints in lieu of the promised holiday in the States; whilst Master Johnny was guilty of strange neglect, for the pet sheep “Billy” —for whose sake he daily committed petty larceny—on that day bah-ah-ah’d unheeded. Moreover, a certain demoralisation had taken place. Hitherto I had never seen any one light a pipe or cigar in the saloons, and now smoking was prevalent, the ladies’ chamber, with its pretty ornaments and luxurious couches, being specially selected as a divan; and this dreadful breach of discipline was regarded with utter indifference by Captain Anderson and Mr. Gooch, the latter being himself one of the chief culprits. One man alone was seemingly unmoved, pursuing his avocation as if nothing had occurred—and that man was the cook; though, as the crowning effect of all, the sound of the dinner-bell lost its accustomed charm.

It had come at last, this evil of evils. There lay the mangled end of the Cable; the other end, with twelve hundred miles of it, being at the bottom of the sea, apparently far from the reach of man. I am not exaggerating when I say that the crash represented a loss of nearly a million sterling, and with it fled, for the time at least, the prospects of the projectors and the hopes of all civilised nations. For though it was immediately resolved to try and grapple the Cable, it was felt that the task was one of great difficulty. We were in a depth of two thousand fathoms, or two nautical miles; and even if we were so fortunate as to succeed in the attempt, the chances of our bringing it on board with such a tackle as we had were slight indeed. We had five thousand fathoms of wire rope, intended to be used for the buoys if required, and it was resolved that so long as it lasted, and indeed until everything available for the purpose was exhausted, there must be no thought of returning to England.

Going back to where the depth was a little under 2000 fathoms we commenced operations by lowering a grapnel with 2500 fathoms of the wire-rope attached. This rope was in pieces of 100 fathoms, joined together by iron shackles and swivels. The grapnel is a species of anchor with five flukes, weighing about 8 cwt., and there being attached at least 500 fathoms of rope over and above the depth of the sea, its whole length trails along the bottom until it meets with some obstruction, which the hooks grapple; and when those extra 500 fathoms are hauled in, and the strain becomes much increased on its leaving the bottom, no doubt arises in the mind of any scientific man that the Cable is securely grappled. Slowly we drifted to the spot where the Cable lay, and at last the vessel turned slowly till her head was brought to wind, showing that the grapnel had met some great obstruction in its passage along the bottom of the ocean. We immediately commenced hauling in the rope at the rate of one mile per hour. When the grapnel had left the bottom, the strain on the dynamometer increased so much each fathom that was drawn in, that no doubt existed that we had succeeded in grappling the Cable, and anxiously we watched foot after foot brought up on board. When 1100 fathoms had been thus recovered, our hopes increasing every minute, an iron shackle gave way, and the remaining 1400 fathoms of rope, with the grapnel attached, fell to the bottom of the sea.

A buoy being lowered, we steamed ahead in order to make another attempt nearer the end of the Cable. Having reached the desired spot, we dropped another buoy, and then lay to, waiting for a change of wind to enable the vessel to drift over the Cable. At noon on the 4th we were enabled to take observations, and found that, during the foggy night and morning, we had drifted between thirty and forty miles.

The operations of the three following days are easily described. The wind being against us, each night we drifted, and each morning, though sorely baffled by the fog, we steamed in search of the buoy, to the finding of which the Terrible was of great service. But when the fog lifted, and allowed us to ascertain our true position, it was useless, with the wind in a direction with the Cable, to attempt to grapple it, for the vessel must slowly drift broadside over it, and for this purpose both the screw and paddle engines are of no use whatever.

Under all these adverse circumstances a gloomy despair fell on us and each day seemed to lessen our chances of success. But whatever may have been our individual hopes and fears, we shunned expressing them, and patience alone was feebly recommended. Wonderful, too, and sad, indeed, was the change in the aspect of the ship. Wandering astern, it seemed like the deserted hive of a once-flourishing community. The long line of lights extending along the paying-out trough from the fore tank, and ending aft in a brilliant illumination of which a theatrical manager might well be envious, is extinct. No blaze from the blacksmith’s forge illumines with ruddy glow the erst-revolving wheels of the paying-out machinery, or the cheery faces of the workmen once around it. The very machine is getting rusty from disuse; the jackdaw has left his accustomed post, and, as if angry at its complete stoppage, has never since been seen. It is a vast solitude, with the signalman for the sole inhabitant; and even he, baffled by the ever-recurring fog, has little or nothing to do. True, there is work going on in the fore part of the ship, but the men are busy there in making appliances to raise the dead, and not to help the living, Cable. The hope that excites men’s best energies is fast slipping away, and, hour by hour and day by day, stronger grows the impression that all human efforts (at least with such tackle as we had) are unavailing to bring to light our lost Cable.

Yet not until those efforts have been tried to their utmost strength will the pluck of such men as Captain Anderson, Messrs. Canning and Clifford, and all under them, give way; so, the weather at last clearing up, on Monday the 7th of August we made for the buoy, in sight of which the Terrible remained with most laudable pertinacity. At 11 A.M. the grapnel was again lowered, and again was the Cable securely grappled; but, alas! a swivel gave way with a loss of 1500 fathoms more of our wire-rope, and once more were our hopes doomed to disappointment.

A consultation was now held amongst the chiefs of the expedition, and it was determined to make a final attempt. There were still 2000 fathoms of wire-rope left, but much of this was useless, and had to be cut out, for the strain on it had been so great that the lay of the rope, which, before being lowered, was only ten inches in length, had been pulled out in parts to twenty-seven inches. The shackles and swivels were all taken out and replaced by others made on board, of better material, and capable of bearing a greater strain. Throughout Wednesday, day and night, the ship presented a scene of great activity. Every carpenter and blacksmith was employed in making such alterations as would most likely prevent the recurrence of such accidents as caused the two former attempts to fail. Little thought of sleep had any one on board. The blacksmith’s musical hammer was heard throughout the night, whilst on the busy scene the forges threw a light which would have sent Rembrandt into an ecstacy.

The picking-up machinery having become disabled from the extraordinary work it had been put to perform, and being at all times but ill adapted for raising the grapnel, it was resolved to use the capstan alone for that purpose; but the diameter of the latter being too small in the centre, strong timbers were fitted and fixed so as to increase it from two feet six to five feet six inches; it was then cased with sheets of iron firmly riveted, giving it the appearance of a solid drum. There being only about 1700 fathoms of wire-rope fit for use, the extra portion required was made up of a thick hemp rope and a good-looking Manilla rope, which seemed capable of bearing any strain. All was now ready for our final attempt, and anxiously we longed to commence operations.

On Thursday, the 10th of August, the wind, which had blown hard throughout the two previous days, accompanied by a drenching rain, suddenly dropped, and shifted to a point very favourable for enabling the vessel to drift over the Cable, which we hoped to grapple much nearer the broken end, so as to have as little strain as possible in hauling it on board. At 7.45 A.M. the grapnel was lowered, and slowly we drifted towards the desired spot; but the summer gale had caused the buoys to shift their places, so that it was noon before we could ascertain the right position. At 1 P.M. the strain increasing gave us hopes that we had grappled the Cable, but it soon ceased, and at 4 P.M., it being concluded that we had passed over it, orders were given to haul in and make a fresh attempt.

So tedious was the process of hauling in, that it took thirteen hours to bring the grapnel on board. It was found covered with a soft pasty substance of a pale yellow color, and several gentlemen having obtained some of the precious substance, it was investigated with a microscope; and Dr. Ward found shells, in one of which there was living matter, thus disproving the assertion that life could not exist at such a depth. At 12.30 P.M. on Friday, August 11th, a day long to be remembered, the grapnel was lowered for the last time, and at 8.50 P.M., the strain on the dynamometer indicating that we had once more grappled the Cable, we commenced hauling in, and at 7 P.M. had succeeded in recovering about 800 fathoms. I was then standing near the capstan watching the rope being drawn in, with an average strain of from 80 to 90 cwt. A snatch-block had been fixed to the deck and to a spar above, through which the rope had to pass in order to bring it on a level with the capstan; no doubt a clumsy appliance, but, unfortunately, the only one available; and, indeed, everything brought into service during the grappling was but an expedient, for it had never been thought possible or probable to perform such an operation at so great a depth, and no preparations had therefore been made. Well, the last shackle of the Manilla rope was passing through the block with heavy jerks when the rope itself snapped at the splice. “Hold on, boys!” shouted Mr. Canning (now only thinking of the men’s safety), and for a moment its lightning speed was arrested by the vigorous arms of the men at the rope-stoppers, thus preventing the destructive rebound, but not for long: escaping from their grasp, it passed swiftly over the wheels, and speeding like a shot from the bow, it fell with a heavy swish into the greedy waters.

ALL WAS OVER. Every yard of material had now been exhausted—what human power and ingenuity could do had been tried—the last hope of recovering the Cable was for the present put an end to; and reluctantly, the order being given, “South-east by east,” the vessel was slowly put on her course to England, the Terrible, after a speedy “good-bye,” proceeding alone to Newfoundland.

For ten days, with little intermission, had this battle been fought; and at last, however unwillingly, human power was forced to succumb: and it did so with dignity; for it is a glorious feature in the natures of most practical men, that failure never produces despair. Whilst there is a thread of hope to cling to, nothing is dreamt of but success; and when the irretrievable disaster comes at last, they at length take their sleep, and, wiping from the brain all of the past that is unavailing, turn their attention solely to the future.

Intensely interesting had been the whole voyage, and especially so to witness this last struggle, though almost hopeless from the first, against superior force, and with materials so ill adapted for the purpose, yet carried on with such persistent energy and such unwearied attention on the part of the chief workers, that even for their sakes alone I could not help deeply regretting that success had not attended such noble efforts. Yet, looking at the amount of experience gained, who shall say that the result is not in a high degree satisfactory? It has been proved that the Cable was of the right specific gravity, and its great strength was shown by its holding the buoys even in a stiff breeze, though the portion used for that purpose had been picked up from a great depth, and had been put to a severe strain; it was proved that the paying-out machinery was absolutely perfect, and that the method employed of paying the Cable out from coils instead of reels is by far the best; it has also been proved that it can be safely picked up at nearly the greatest depth known in the course taken between Valentia and Newfoundland; and lastly, to the wonder of all on board, it has, been proved that it can even be grappled at that depth, and that with proper tackle there would be every probability of its being raised successfully.

Much unnecessary, and I venture to think unjust, censure has been cast on the engineers, by those wise people who judge after the event, for the inefficiency of the picking‑up machinery. The real progress of science must ever be affected by circumstances, and perfection can only be safely reached by the sure paths of experience. Messrs. Canning and Clifford had hitherto found the apparatus in use perfectly satisfactory, and during this voyage it had picked up the Cable from a depth of two miles; nor, with the exception of the breaking of a bad valve-rod, which really caused no delay, did it fall to pieces until after grappling had commenced. Now Mr. Canning’s observation when the Cable broke—"ALL IS OVER!” —proves that grappling at two miles was never contemplated, and was resorted to rather as an experiment than with any hope of success; but now that it has been proved that the Cable can be grappled at so great a depth, no doubt the skill and ingenuity of those practical engineers will make the machine fit for hauling in the grapnel, and proof against any strain to which it may be subjected. To require human foresight to provide for evils utterly unknown, is simply demanding an impossibility. I have the best authority for stating that had the picking-up machine been used solely for the purpose for which it was made (with the trifling exception alluded to), we should have returned to Sheerness with all its gear as perfect as it was when we started. *

We had a very fine passage home, never shifting our sails till after we passed Cape Clear, and at a speed of nine knots per hour, which, under all circumstances, was more than we expected. I could have wished to have obtained some details as regards the consumption on board. Of our live stock there only remained fifty sheep, a few pigs, and some score or so of fowls; but the havoc made must not be wholly ascribed to the voracity of man. In taking my morning stroll amongst the animals I daily noticed a gap in the oxen-shed, and knowing that there was plenty of fresh meat in the ice-cellar, I was anxious to know the reason. The butcher (he is not an Irishman) informed me that the oxen were killed in order to save their lives, and that their gradual decay was owing to the water they drank. I am not sufficient of a chemist to know the properties of condensed water, but however great a blessing is the discovery of turning the sea-waves into fresh water, it certainly does not contribute to the prolongation of animal life. It had been death to the ducks, the cow, and the oxen; nor had it improved the sheep, so destroying their natural instincts that they tamely submitted to the interested caresses of their greatest enemy, the two-legged wolf. The pigs alone have thrived, but on what will they not fatten and grunt? To dismiss these interesting creatures: the fifty sheep have been purchased by Mr. Gooch; and “Billy,” round whose neck the young Russells tied a pink string to save him from the butcher’s knife, is to pass the rest of his days in clover.

Early on Thursday, August 17th, we reached Crookhaven, and there Dr. Russell, with three other gentlemen, left us. And here I would offer a word of advice. If you wish your friend to retain a lively impression of you, don’t get up early to see him depart. A more miserable set of unwashed, uncombed, unrefreshed, half-awakened, and breakfast-craving mortals I never beheld, than the gentlemen who crowded the paddle-boxes to give a parting cheer to those who then left the ship.

Reaching Lizard Point on Friday morning, we steamed up the Channel, which was was smooth as glass, and hove-to, at 9 A.M. on Saturday, about two miles from Brighton, where many of the passengers landed; and on Sunday at noon the Great Eastern was anchored at her old moorings, having been absent five weeks and one day.

And thus, with the fairest prospect of success—in spite of arrangements made with the utmost liberality, rid in spite of the great skill and care bestowed in carrying them out—either through accident or design (let us hope the former), one of the noblest enterprises ever undertaken by man has for the moment failed. But it is not in the nature of the Anglo-Saxon to accept defeat as final, but rather to look on each failure as a step nearer to success. Let all honour be paid to those who have worked so bravely to obtain a satisfactory result. It is from the knowledge of their great abilities the belief is encouraged that time alone is wanted to insure complete success. With such a ship as the Great Eastern, guided by so skilful a commander as Captain Anderson, and with such men as Messrs. Canning and Clifford to superintend the machinery, and Messrs. de Sauty and Saunders to conduct the electrical operations, there is every reason to indulge in the most sanguine expectations.

Yet is there wisdom in not being over-confident. Sweet are the exulting poeans of victory, but it were better not to sound them until the battle is won. It is well to be hopeful and sanguine, for except under the influence of such feelings no great work can over be accomplished; but to express those hopes as if they were already realized, before an atom of work has been done to insure success, will too often lead to regret and mortification, as, unfortunately, has been the result in the present instance.

And yet I have no doubt whatever of final success. No matter what, faults arise, whether caused by accident or malice, with picking-up machinery as perfect in its working as that made for paying out the Cable, no more serious misfortune can happen than is produced by a temporary delay. The next expedition, I hope and believe, will meet with complete success; and my only wonder is, that such has not been the result of the present undertaking.

HENRY O’NEIL, A.R.A.

* Since writing the above I have heard with pleasure that the Great Eastern is to lay a fresh cable next summer, and then return to grapple the one just lost It has been supposed that the buoys will not remain where they were placed; but they were never put there for such a purpose. Of course it would be very pleasant and curious to find them still tossing where they were left; but as a mark they are not necessary, as the skill of Captains Anderson and Moriarty can find the desired spot without any such assistance.

1866 Expedition

LONDON SOCIETY.

An Illustrated Magazine

OF

LIGHT AND AMUSING LITERATURE

FOR

THE HOURS OF RELAXATION.

A SUMMER TRIP ACROSS THE ATLANTIC.

In Reminiscence

BY ONE WHO HELPED TO LAY THE CABLE.

DEAR MARCUS,

You, who have listened with credulity to the whisperings of wiseacres, and have followed with eagerness the foreboding phantoms of mock wisdom—who have expected that time would fulfil the despairing prophecies of the newspapers, and that the disasters of last year would be repeated in this, attend to the tale of the successful laying of the Atlantic cable.

I dare say, now that you have read so far, your wonder at receiving so big a parcel by the post is a little allayed. I presume you do not forget the promise you exacted from me in June last, when you bade me good-bye on board the ‘Great Eastern.’ As you were leaving the ship, with a certain sweet young thing (who shall be nameless) upon your arm, you said, ‘Good-bye, old fellow, mind you drop us a line when you get back, and tell us all about it.’ Now do you remember?

To tell you all about it would be simply ridiculous. I am well aware that, in common with all other Christian gentlemen, you see the ‘Times’ daily, and that you have read the accounts forwarded to that paper from time to time by our historian, Mr. Deane. I shall therefore confine myself to such matters as have not been narrated in the daily papers, and will endeavour to amuse you for a few minutes with a little ‘Great Eastern’ gossip, and try to give you some insight, however slight, into the daily life on board the great ship.

A small paper packet accompanies this letter. Do not throw it away. It is of exceeding value, a pearl of great price. It is not one of Dr. Gregory’s far-famed powders, nor is it a portion of sand scraped from the roadside. It is something far more precious, though it may not appear so to the naked eye. It is ooze from the bed of the Atlantic Ocean, that came up on one of the grappling-ropes, and which I picked out from the interstices of the same, by means of great patience, an old penknife, and the point of a breastpin. If you do not appreciate it yourself, make a handsome present to some of your scientific friends, and they will love you and venerate your name for ever after. I will give you, however, one word of advice. Do not let the world in general know that you are the possessor of such an invaluable treasure, or you will be tormented out of your life. Every post will bring letters in strange handwritings that will worry a man of your nervous temperament into a fever. There comes a rat-tat at the door, and in a minute a budget of letters is handed in, in all kinds of envelopes and external coverings, and directed in every species of caligraphic character, with none of which you are acquainted. Yon have a vague idea that the big blue letter is a gentle reminder from Mr. Snippit, ‘that you would greatly oblige him by settling his little account;’ but on opening it you find, to your delight and amazement, that it is only from little Mudlark, the amateur geologist, whom you once met for five minutes during a morning call, and who, strange to say, has taken upon himself to write to you. Through four sides of a sheet of note-paper he goes on to say that, through the medium of the daily press he has watched the progress of the truly national work with great interest; that he is sure that your untiring zeal and energy have mainly contributed towards the glorious success; and that when a grateful government raises you to the peerage, no one will rejoice more sincerely than Theophilus Mudlark, and—and could you oblige me with a small quantity—only a few grains—of ooze?’ This is a fair sample of the curiosity-begging letter, but they are numerous in number and diverse in sentiment. One correspondent (of course a lady) ventures to ask ‘if she may enrich her photographic album with the counterfeit presentment of so distinguished a character as yourself;’ another would feel more than grateful if you would give him a short piece of the ‘magic rope’ for the Snoozleum Museum; and a third requests a small present of some other kind, say, ‘a model of the paying-out gear,’ ‘the grapnel,’ or ‘a yard of the grappling-rope.’ Take warning, therefore, and keep a discreet silence on the subject of the ooze.

The trip round the Channel, from Sheerness to Beerhaven, was a lark, in fact it was four days’ yachting in the finest yacht that ever floated. The weather was glorious; the spirits of all on board were at the highest point; a generous board of directors had looked nobly after our creature comforts, and, in addition to all this, there were some twelve or fourteen ladies on board, who added materially to the elegance, the comforts, and the pleasures of this part of our voyage. Perhaps the best fun we had going round was the performance of the ‘Field Glass,’ a burlesque, in fact, by Messrs. Woods and Parkinson. This was a good-humoured skit on the whole of the undertaking, and occasioned not a little laughter and merriment, more especially as no one who was at all prominently connected with the enterprise escaped the good-natured lash of the satirist. The performance was most grand. By means of union jacks and ensigns we rigged up a first-rate theatre in the grand saloon, with a row of footlights and an orchestra, quite like the genuine article. The gentlemen of the press occupied several of the front seats, and when the curtain rose and discovered two lovely mermaids and a Triton enjoying a siesta, there was quite a burst of applause, that reminded one of Boxing-night. How those sweet mermaids got dressed will always remain to me a mystery. They were a sort of composition ladies, half ballet-girls and half John Bright to look at, but lovely withal. If their waists were a trifle bigger than would be admitted as ‘correct’ in the pages of the ‘Follet,’ why let us say that it was the fault of the dress; and if the size of their shoes was something over ‘six and a half ladies,’ let us put down the fact to the score of the maker. Whatever individual faults carping critics may have detected, I am positively certain that the tout ensemble was perfect; and even at this distance of time my pen trembles as I write on the subject of those truly elegant ‘critturs’ .

The tranquillity of the opening scene was soon disturbed by Neptune, got up in the mythological style, who entered, quickly followed by Mr. Dudley, arrayed exactly like Mr. Glass. The entrance of this last gentleman was the signal for fresh applause. The resemblance in dress, manner, and make-up to the person he was supposed to represent was so extraordinary, that the audience could scarcely believe their eyes, and as they looked from the original, who sat in the front row of the stalls, to the actor on the stage, the laughter rang out in louder peals than ever. It was quite like a scene from the ‘Comedy of Errors.’ Which Dromio was which? No one seemed to enjoy the joke more than Mr. Glass himself, who applauded and laughed with the loudest. That he may rise from his sick bed, and live many years to laugh again, is, I am sure, the sincere prayer of all connected in any way with the Atlantic telegraph. Seems it not sad, on the completion of a great work, the dream of years, that the prime mover of the whole affair should be unable to participate in the rejoicings around him, but should be obliged to send his congratulations and receive his well-merited honours on a bed of sickness, prepared for him by over work and over anxiety for a great cause? When we got to Beerhaven, all our fair fellow-travellers took their leave, and left us alone. This was sad indeed; but one cannot be dull on board a ship like the ‘Great Eastern,’ where so much of interest is daily going on.

There were now several arrangements to be made before we started on the real business of the expedition. Some thousands of tons of coal had to be taken on board, and for this purpose nearly a hundred of the native peasantry had been engaged. Their pay was to be 5s. a day and their rations, and yet, notwithstanding the munificence of the stipend, devil a bit would they work. No, they were full of excuses. ‘Oh, bedad, your honor, I’ll do as much work as ony man, barring it’s not in a caul hole.’ ‘Put me in the open fields, your honor, to hay mowing or cow milking, and I’m the boy that will tire out the parish; but, by jabers! ’twould tear the soul out of ony man to work all day with his mouth so full of cinders that be can’t spit.’ And so on, through fifty or sixty. The end of it was, that they all had permission to go, and the 5s. per diem was given to the ship’s men, who were glad enough to get it, and willing to work.

The ‘Great Eastern’ is a wonderful ship, but not until you have lived on board her for at least a week are you fully aware of her size. Every day one comes across something new that strikes with amazement. As an instance of this, let me mention the shorings of the tanks. It is exceedingly unpleasant to have to perform the journey necessary to see them, but in the end the adventurous traveller is well repaid. Yon cannot see much after all, except what is revealed by the light of an oil lamp, for in these regions darkness reigns supreme. What this part of the ship was used for before the tanks were erected I have not an ides, but now it presents the appearance of a dead forest, all the trees of which have been roughly trimmed. The amount of timber used for supporting the tanks is simply appalling, and must be reckoned by shiploads. Huge beams stretch in all directions, vertical, horizontal, and diagonal, tiring the eye by their similarity and numbers, and giving an idea of almost unnecessary strength. This may be so as long as the ship is at rest, but when she begins to roll, as she alone knows how, it must be work of extraordinary solidity, and put together with great engineering skill, that will bear up against a dead weight of 2000 tons pressing upon it in all directions. Another remarkable spot is the ship’s ice-house, where were stored some 100 tons of ice and nearly 20,000 lb. of dead meat. Another spot worthy of notice was the farm-yard in the bow of the ship. Here was a flock of 114 sheep, a herd of 10 oxen, a milch cow, and 36 pigs, besides 300 head of poultry. By closing the eyes, and simply listening to the chorus of bleating, lowing, cackling, and crowing, one imagined oneself in a large farmyard in the depths of Hampshire rather than on board the ‘Great Eastern.’