Introduction: In covering the news of the 1865 Atlantic cable expedition, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, published in New York, had the same problem as in 1858—with communications from Europe received only by ship, the news was generally three weeks delayed in arriving in America. In Britain, by contrast, the London papers could be in almost instantaneous contact with the telegraph office at Valentia, and could also receive messages from Great Eastern, which were sent to Valentia over the cable as it was being laid, and relayed from there to England.

Undeterred, Leslie’s despatched its correspondent and artist (Carl J.) Joseph Becker to report on the 1865 expedition. He had joined the paper in 1859 as an errand boy, but his artistic talent led to his being sent in 1863 to accompany the Union Army during the American Civil War, and approximately 88 of his wartime drawings were published in the newspaper between 1863 and 1865. In 1875, he became manager of Leslie’s art department, a post he held until his retirement in 1900. Becker died in Brooklyn, New York.

Becker was accompanied by Charles H. Farrell, correspondent of the New York Daily Herald, whose story on how the cable landing site was selected was published in that paper on 20 June 1865. Farrell also provides an interesting and sometimes amusing description of how the party made its way from London to Valentia.

Some of the original drawings made by Becker and other artists employed by Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper are preserved and archived at Boston College in Massachusetts. Ten of Becker’s cable-related drawings, mostly from England and Ireland, but also including one made in Newfoundland, may be viewed on the Becker Collection website, together with detailed biographical notes on Becker.

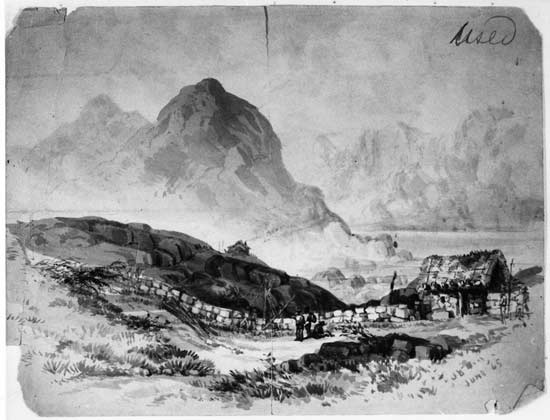

By kind permission of the Becker Collection, Joseph Becker’s original drawings of Atlantic cable scenes are shown below, each immediately following the illustrations as published in the newspaper (where available). It is interesting to note how much more detail Leslie’s wood engravers have put into the published illustrations, often considerably embellishing the original sketches. But as one of the Becker Collection curators notes, the original drawings show the immediacy of the situation and reveal the artist’s emotions and point of view at the time.

The newspaper’s first published report on the Atlantic cable enterprise was in its issue of 25 February 1865, describing and illustrating the loading of the cable from the factory at Greenwich onto the hulk Iris for transport to the Great Eastern. These operations began on 19 January and continued for several months. Then on 22 April the newspaper published an update on the project and stated:

“We have already dispatched a Special Artist to Europe to accompany the Great Eastern, and illustrate everything of importance connected with her mission.”

The exact dates of Becker’s visit to England and Ireland are not known, and I can find no record of his name in ship passenger lists of 1865. However, his last Civil War sketch prior to the period of the cable drawings is dated 16 April 1865, which would agree with the dispatch date above. That would place him in England in early May 1865.

The issue of 1 July 1865 had a story describing the completion on 29 May of the manufacture of the cable at the London factory. The illustration had no credit line, although it could certainly have been by Becker, who must have been in London on that date. The first mention of him by name is in the issue of 15 July, where it was reported that he had travelled to Ireland with Cyrus Field and other officials and engineering staff of the telegraph companies, leaving London on the morning of 1 June. As noted above, see Charles Farrell's account in the New York Daily Herald for details of that journey.

The Cork Examiner reported in its issue of 6 June that the party had inspected possible landing points “on Saturday,” which would have been 3 June 1865, although Leslie’s has the date as Sunday 4 June. This event was covered in the paper’s issue of 17 July 1865 with five illustrations by Becker; it was the first story on the cable with images specifically credited to him. The report concluded with this note:

“We present this week some spirited sketches by our Special Artist, who was present during this trip, and will sail on the Great Eastern to witness the laying of the cable.”

But the directors of the Atlantic Telegraph Company had delegated control of the expedition to the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company, and this firm had other ideas. The company refused to allow any correspondents on board Great Eastern for the voyage, or indeed anyone not considered essential to the project. For reporting on the expedition they contracted with William Russell, the war correspondent of the Times of London to write a book on the expedition, illustrated by Robert Dudley and to be published by Day and Sons at the conclusion of the expedition. Russell had also arranged to provide a daily diary of the expedition to newspapers in Britain and North America.

In its issue of 26 August 1865 Leslie’s made this complaint:

“For some motive, it is impossible to conceive what one, the contractors for the great Atlantic Telegraphic Cable, rigorously refused to permit reporters aboard the Great Eastern.”

Great Eastern began laying the cable between Ireland and Newfoundland on 23 July. Denied permission to travel with the expedition, Becker either took passage directly to Newfoundland on another vessel, or perhaps sailed somewhat earlier to New York and from there on to Newfoundland. Whatever his route, by early August he was awaiting the arrival of the expedition at Heart’s Content, but after the loss of the cable on 2 August and the abandonment of the expedition on 11 August, the ship returned directly to Britain. The accompanying ship Terrible arrived at Newfoundland on 15 August with the news of the failure of the expedition, and on 18 August the New York Times published a brief summary of the loss of the cable. Leslie’s did not publish this information until 23 September.

Drawings by Becker continued to be published in Leslie’s during August, but these had obviously been made earlier in the year in England and Ireland. Two sketches credited to Becker at Newfoundland were published on 9 September and 16 September, both depicting incidents from the first half of August. The last story from Newfoundland, published on 30 September 1865, was an account of the British war steamer Galatea firing shells at an iceberg while waiting for the arrival of Great Eastern. This story also had an illustration credited to Becker.

Along with uncredited images, seven of Joseph Becker’s cable-related drawings were published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in 1865. I have provided a direct link to the original sketch for each of these, and have also quoted some of the handwritten notes on the backs of the originals.

The stories and images are presented in chronological order of publication, which does not necessarily correspond with the sequence of their creation, and, as noted earlier, news from England was generally three weeks late by the time it was published in New York. The dates on each story are the issue date of the newspaper in each case. |

| -- Bill Burns |

|

|

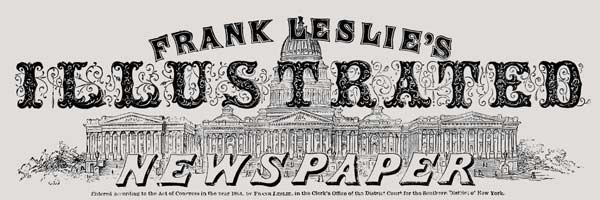

18 February 1865

The manufacture of the great Atlantic telegraph cable is progressing very satisfactorily, The length made now averages 80 miles per week. As it is necessary that the cable should be kept constantly immersed in water, eight large tanks have been constructed to contain it, from which it will be coiled into the Great Eastern. The entire cable will be ready by June next.

25 February 1865

SHIPPING THE ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH CABLE.

The process of shipping a portion of the submarine cable which has been made for this great undertaking from the works at Greenwich on board the hulk Iris, for transference to the Medway, and final stowage in the tanks of the Great Eastern, was commenced on Thursday, the 19th ult. [January]. The shipment was begun early in the morning, and will continue without intermission now until nearly the end of May, by which time it is hoped all will be coiled away snugly on board the great steamship. The total quantity of rope required to connect Valentia with Bull’s bay, Newfoundland, allowing for the ‘slack’ which must run out to prevent too great a strain on the cable, is about 2,300 nautical or nearly 2,700 statute miles. With this length a liberal margin is given of nearly 600 statute miles of rope or slack caused by currents, possible rough weather, and the avoidance of anything like unusual strain on the cable in the deepest water. Over one part of the route the depth is as great as from 2,000 to 2,500 fathoms, or nearly three statute miles—a depth, however, which is only considered of moment in case of rough weather in paying out, the mere strength of the cable being sufficient to bear its own weight in 11 miles of still water. In this respect, as indeed in all others, the new cable has an enormous superiority over the old and ill-used rope, which was first laid, and which, to the amazement of all those who knew its real condition, nevertheless remained in fair working order for a few days.

Shipping the Atlantic Telegraph Cable at Greenwich |

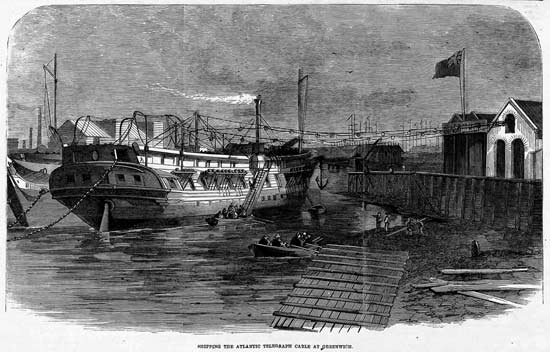

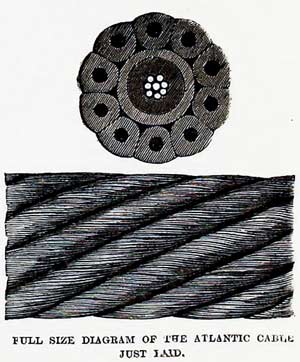

Our engraving shows the process of running off the cable from the works into the receptacle prepared for it on board the Iris. We also give transverse and longitudinal sections of the cable.

Transverse & Longitudinal Sections of Cable |

18 March 1865

The Great Eastern will be ready with the entire Atlantic cable on the 1st of June.

22 April 1865

The experiment of laying an “Atlantic cable” is to be repeated within the next three months, and this time with every prospect of permanent success. The experience of the past six years will be called into requisition, and all the appliances of science and skill will be lent towards the achievement of this great and good undertaking. The “Great Eastern,” the leviathan of steamers, will carry the cable which is to link together the two continents, and traverse the unknown depths of ocean. She is to sail from Valencia, Ireland, about the 1st of July, and may be expected at Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, about the middle of the same month. There were 1,662 nautical miles of the cable completed on the 21st of March, and the whole 2,300 miles were to be aboard the Great Eastern in May. Two powerful steamers of the British navy have been designated to accompany the Great Eastern to Newfoundland, and lend such aid as may be necessary. It is expected that Europe and America will be in permanent communication on or before the 1st of August, and that the initial message from President Lincoln will be that the United States, “one and indivisible” in peace at home, sends to Europe the Scriptural adjuration, “Peace on earth and good will among men.” We have already dispatched a Special Artist to Europe to accompany the Great Eastern, and illustrate everything of importance connected with her mission.

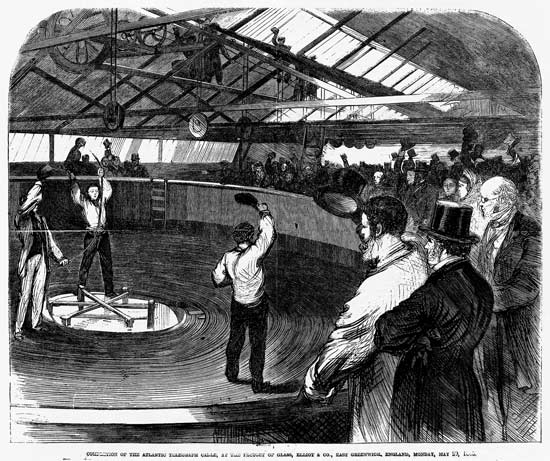

1 July 1865

THE ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH AND ITS COMPLETION IN ENGLAND.

On Monday, May 29th, the last mile of the great nerve which is to connect the Old with the New World was completed, and wound through the last of the covering machines in England, in the presence of a large number of distinguished electricians, engineers, merchants, and in a word all the leading scientific gentlemen, including the Directors of the Telegraph Maintenance Company.

Only one machine had half a mile to complete—that is to say, to case the core with Mr. Wright’s most ingenious and simple patent of wire inclosed with strands of hemp, which form the outer covering. When all the visitors were assembled this was started, and the core wound regularly and clearly through the centre of the machine, which, revolving at a great speed, completed the outer case of hemp and iron. When the last portion of the cable had passed from the machine, and the end was held out by the acting superintendent, the persons present gave a hearty cheer in evidence of their satisfaction of the completion so far of this great undertaking. Working 14 hours a day, each machine was able to cover four miles an hour; the average rate of manufacture for the four machines employed being about 17 miles per day.

Completion of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable, at the Factory of Glass, Elliot & Co., East Greenwich, England, Monday, May 29, 1865 |

As the cable was drawn out of the machine it passed through a gauge, which compressed it firmly, and then out of the manufactory away to the tanks, where it was coiled under water, and every change is its electrical condition noted with a care and minuteness that have certainly never yet been applied to any other cable. From first to last, indeed, it has been subjected to a series of the most searching electrical tests, the standard of insulation being fixed at a resistance per nautical mile equal to 150,000,000 of Siemen’s units, at a temperature of 75 degrees—a standard wholly unprecedented in any former work of the kind. In actual practice these tests, great as they were, have been considerably exceeded, and the present Atlantic cable has come out successfully from a series of trials of the most crucial character.

Towards five o’clock on Monday the last few fathoms of the great coil began to be drawn into the machine, and in a few minutes after the end was wound up a self-acting bell rang to give notice that the machine was empty, and almost at the same moment the end came down on the tank, and the last coil of the cable was stowed away. The next great object of interest was the inspection of the paying-out apparatus, which has been already fixed up, and, by means of an endless band, kept constantly running.

The present cable is just 2,300 nautical miles, or about 2,700 common miles. The central conductor is composed of seven fine copper wires, twisted into one complete strand, which is insulated with Chatterton’s patent compound. Outside this are four distinct layers of gutta-percha, each also insulated with the same material, which encloses the conductor. Outside the gutta-percha again are wound 11 stout iron wires, each of which before being twisted on, is itself carefully wound round with strands of rope soaked with tar. It is stowed away in three boilers; the first contains 630 miles of cable, the second 840, and the third one of 830. All the tanks are kept filled with water, and when each is stowed with cable as well, the ends of the wire will be joined up, and a constant system of signals kept through every part from the moment the expedition starts till the whole cable is laid. The weight of the tanks, with their contents, including the water, is 5,000 tons. The Great Eastern will draw 30 feet when starting from Valentia, and will come near the stupendous mass of 18,000 tons.

8 July 1865

The Great Eastern will probably sail from the Nore on the 5th of July, and from Valentia about the 10th of July.

15 July 1865

THE ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH CABLE.

The magnificent enterprise of extending telegraphic communication across the Atlantic Ocean bids fair to be completed very soon. The public will remember the previous attempt, which, after a brief and partial success, resulted so unfortunately. This time additional skill has been brought into operation, and the experience of the past is expected to lead the way to success.

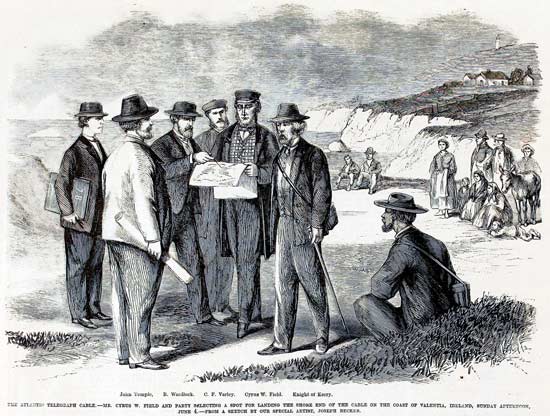

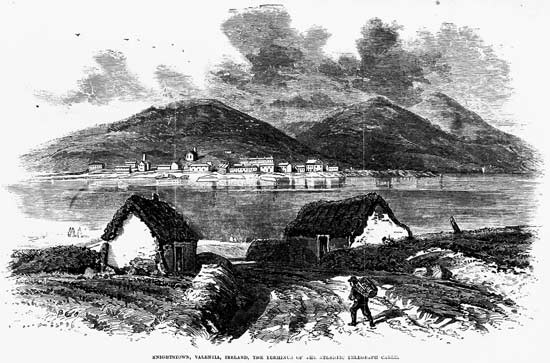

On the morning of June the 1st, the scientific corps, chosen to select a site for the British terminus of the great cable, left London for Valentia bay, on the west coast of Ireland. The corps consists of the Hon. Cyrus W. Field, of New York, on behalf of the Atlantic Telegraph Company; Mr. C.F. Varley, Assistant Electrician to the same company; Mr. John Tremble [actually Temple and correctly identified both on Becker’s drawing and in the published caption], Engineer to the Telegraph and Maintenance Company; Mr. B. Dawson Wardlock [actually Watlock], Superintendent in Ireland of the Atlantic Telegraph Company; Mr. W.T. Ansell, Superintendent Engineer and Inspector to the International Electric Telegraph Company; the Knight of Kerry, a gentleman who has taken great interest in the project; and our Special Artist, with one or two newspaper correspondents. The party passed through the counties of Dublin, Kildare, Kings, Queens, Kilkenny, Tipperary, Limerick, Waterford and Cork, and passed the beautiful lakes of Killarney, reaching Reenard Point, extending into the harbor of Valentia, at eleven o’clock at night. Doulas bay, the place where the shore end of the cable of 1858 was fastened, is near this place. Knightstown, Valentia island, is selected for the place on this occasion, a pretty little village, cosily resting at the foot of huge cliffs on the shore.

We present this week some spirited sketches by our Special Artist, who was present during this trip, and will sail on the Great Eastern to witness the laying of the cable.

Left to right: Unidentified, John Temple, B. Wardlock [actually Watlock], C.F. Varley, Cyrus W. Field, Knight of Kerry, Unidentified

The Atlantic Telegraph Cable—Mr. Cyrus W. Field and Party Selecting a Spot for Landing the Shore End of the Cable on the Coast of Valentia, Ireland, Sunday Afternoon, June 4.

From a Sketch by our Special Artist, Joseph Becker [original below]

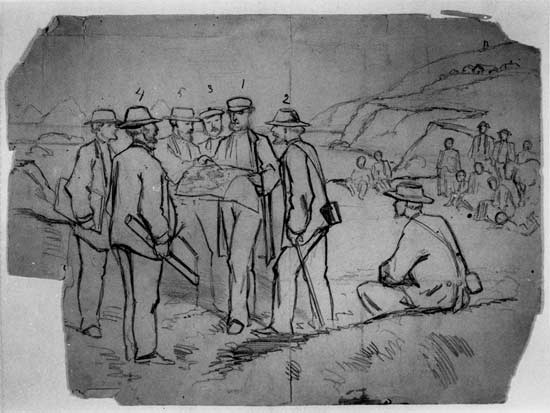

Original Becker sketch TAC-JB-GB-6-5-65-2

Courtesy of the Becker Collection, Boston MA

Becker’s original drawing has these notes on the reverse:

“Cyrus Field and party selecting the location for landing the shore end of the cable on the Coast of Valentia. Sunday afternoon, June 5.”

“This is almost as important as laying the cable itself and Mr. Field traversed the island time and again before deciding on the matter a smooth water and sandy bottom being necessary for the safety of the cable.”

“1 Cyrus W. Field”

“2 Knight of Kerry ( A [?])”

“3 C. F. Varley Asst. Electrician to Atlantic Telegraph Co”

“4 B. Wardlock Supt in Ireland of the Atlantic Co”

“5 John Temple Engineer to the Telegraph and Maintenance Co London”

“See Farrell's letters to the Herald, J.B.”

"The shore end of the cable will be carried out to sea about 15 miles and there buryed until the arrival of the Great Eastern when it will be connected with the Main Line. Consequently the ship will not come within sight of Valencia. ” |

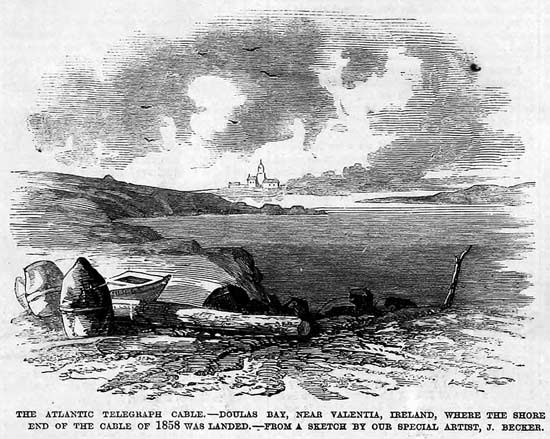

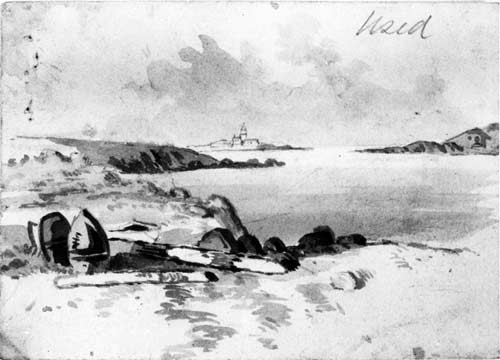

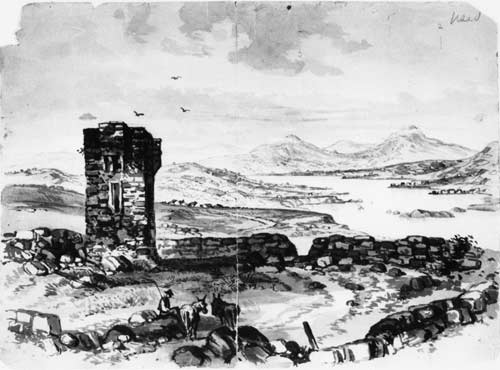

The Atlantic Telegraph Cable—Doulas Bay, near Valentia, Ireland, where the Shore End of the Cable of 1858 was Landed.

From a Sketch by our Special Artist, J. Becker [original below]

Original Becker sketch TAC-JB-GB-65-3

Courtesy of the Becker Collection, Boston MA

A note on the back of this original drawing reads:

“Doulas Bay, the place where the shore end of the Atlantic cable of 1858 was landed near Valentia Island. This is the place where the old cable was landed. The new locality saves 6 miles of wire.” |

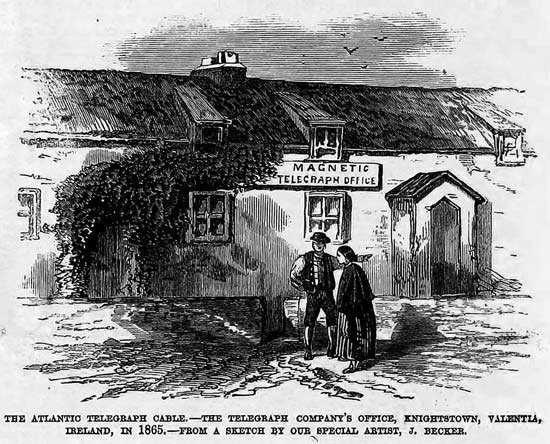

The Atlantic Telegraph Cable—The Telegraph Company’s Office, Knightstown, Valentia, Ireland, in 1865.

From a Sketch by our Special Artist, J. Becker [original below]

Original Becker sketch TAC-JB-GB-6-5-65

Courtesy of the Becker Collection, Boston MA

Notes on the back of the original drawing read:

“The Atlantic Telegraph Cos. office Knightstown, Valentia Island, June 5.”

“

All these subjects sketched at Mr. Fields request. J.B.” |

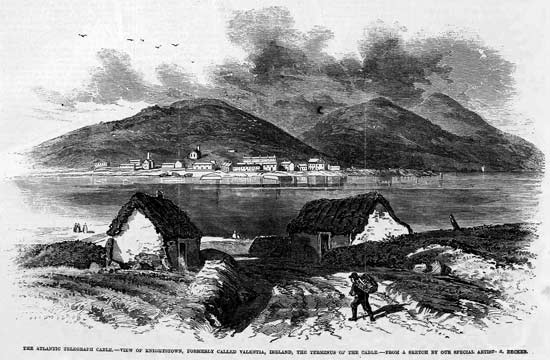

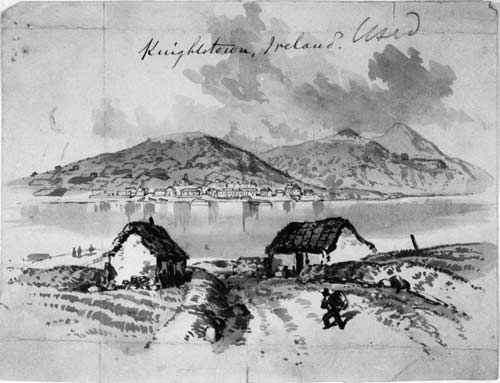

The Atlantic Telegraph Cable—View of Knightstown, Formerly Called Valentia, Ireland, the Terminus of the Cable.

From a Sketch by our Special Artist, J. Becker [original below].

Original Becker sketch TAC-JB-GB-6-5-65-1

Courtesy of the Becker Collection, Boston MA

Notes on the back of the original drawing read:

“View of Knightstown (sometimes called Valentia) and the island of Valentia the terminus of the Atlantic cable.”

“See letters to the Herald, JB, Sunday, 5 June.”

“The London Ilustrated [sic] News have been refused a passage in the ship as also the New York Times. Myself and Farrel will have it all our own way.”

Charles H. Farrell was the correspondent of the New York Herald—but see the note in the introduction and the 26 August story in Leslie’s, below.

|

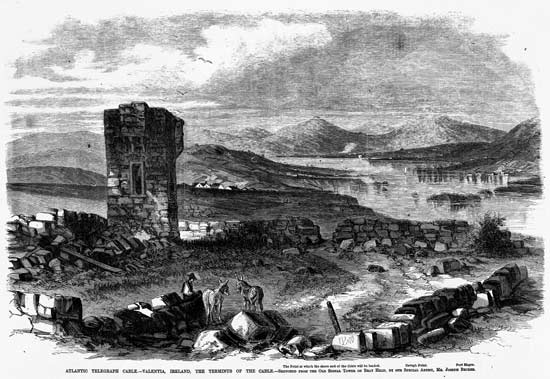

The Atlantic Telegraph Cable—Valentia, Ireland, the Terminus of the Cable. Sketched from the Old Signal Tower on Bray Head, by our Special Artist, Mr. Joseph Becker [original below].

Original Becker sketch TAC-JB-GB-6-5-65-3

Courtesy of the Becker Collection, Boston MA

Notes on the back of the original drawing read:

“View of Valentia Bay, Ireland the terminus of the Atlantic Telegraph sketched from the old signal tower on Bray Head.”

“1 Carash Point”

“2 Port Magee”

“3 The Point at which the shore end of the cable will be landed”

“Sunday June 5th 65. For full description see Farrell’s letter to the 'Herald'.” [Sunday was actually June 4th.] |

22 July 1865

The whole length of the Atlantic cable was on board the Great Eastern, and the telegraphic fleet was expected to sail on the 10th of July for Valentia Bay. The tariff of charges for telegraphing is issued. The terms are: To England, 20 words or less, $100 in gold; for each additional word, $5. To the Continent, 20 words, $105; each additional word, $5.25. To Asia or Africa, 20 words, $135; each additional word, $6 25.

12 August 1865

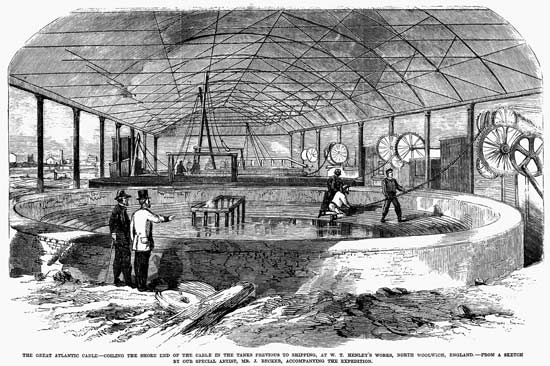

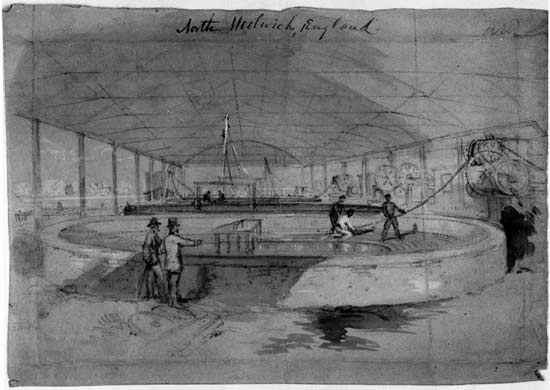

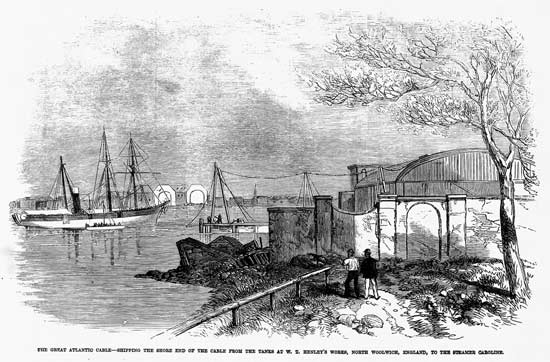

THE GREAT ATLANTIC CABLE.

Our present number contains several interesting sketches from our Special Artist in England, illustrating the progress of the great electrical event of the age, the result of which we may expect to hear in a few days.

The Great Atlantic Cable—Coiling the Shore End of the Cable in the Tanks Previous to Shipping, at W.T. Henley’s Works, North Woolwich, England.

From a Sketch by our Special Artist, Mr. J. Becker, Accompanying the Expedition [original below]

Original Becker sketch TAC-JB-GB-65

Courtesy of the Becker Collection, Boston MA |

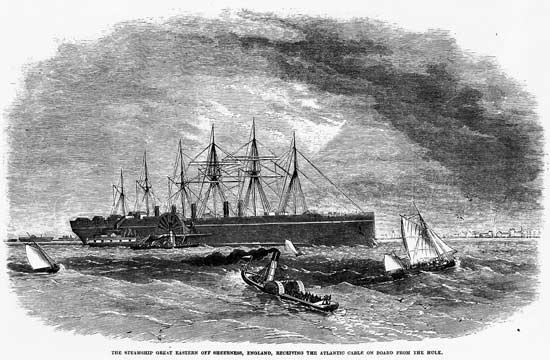

One of our illustrations represents that most interesting moment when the shore end of the cable was being shipped. Our readers need nothing to convince them what a monster the Great Eastern is; but our correspondent says that, although it was blowing a gale, and it was dangerous to attempt to board the ship in a tug, she lay perfectly motionless, almost as steady as a rock in the ocean. It may give the reader some idea of the immense weight on board, when we inform him that it was over 27,000 tons. All the weights are stowed as low as possible, to counteract to the utmost the tendency which large ships have to roll. On the voyage round to Valentia both screw and paddles will be used, but during the laying of the cable only the screw, except on special occasions. The paddles, however, will be kept constantly under steam, so as to be ready at a moment’s notice.

The Great Atlantic Cable—Shipping the Shore End of the Cable from the Tanks at W.T. Henley’s Works, North Woolwich, England, to the Steamer Caroline. |

There has been the greatest exclusiveness shown by the directors, only one of that influential body being allowed on board. Messrs. Canning, Clifford and Temple have absolute charge of the engineering department, and Mr. De Santo [actually deSauty] of the electrical. Professor Thompson [actually Thomson], a man of great eminence in the profession, is to be the referee in case of any difference of opinion.

The Great Eastern was expected to leave her moorings on the 15th July, and most probably would leave Valentia about the 19th July. At the rate of six miles an hour, she would be due at Heart’s Content on the 3d of August. We hope our next paper will chronicle and illustrate her arrival there, and the triumphant completion of the great undertaking.

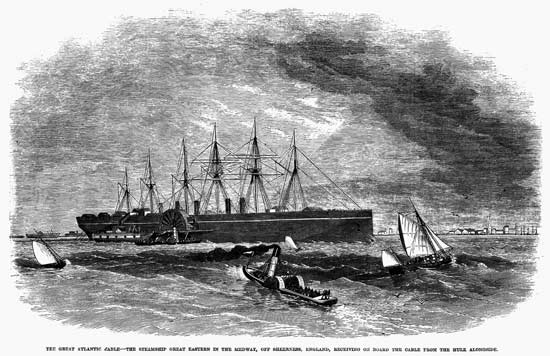

The Great Atlantic Cable—The Steamship Great Eastern in the Medway, off Sheerness, England, Receiving on Board the Cable from the Hulk Alongside.

As was common in illustrations of Great Eastern as a cable layer, the ship is shown with five funnels rather than the correct four. The artist presumably worked from an older image of the ship rather than from life. |

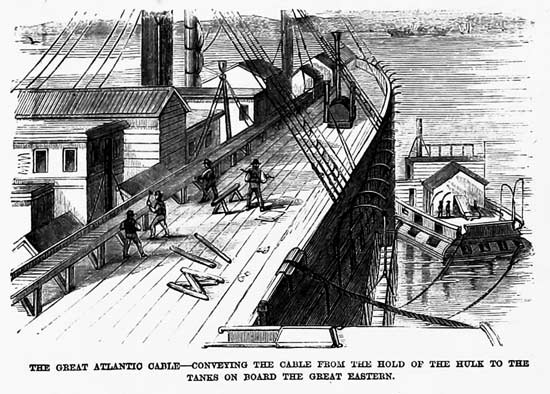

The Great Atlantic Cable—Conveying the Cable from the Hold of the Hulk to the Tanks on Board the Great Eastern |

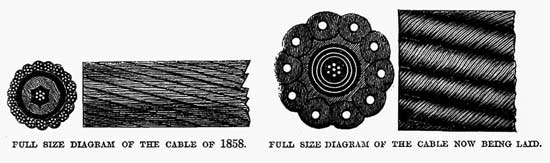

Full-size diagrams of the cables of 1858 and 1865 |

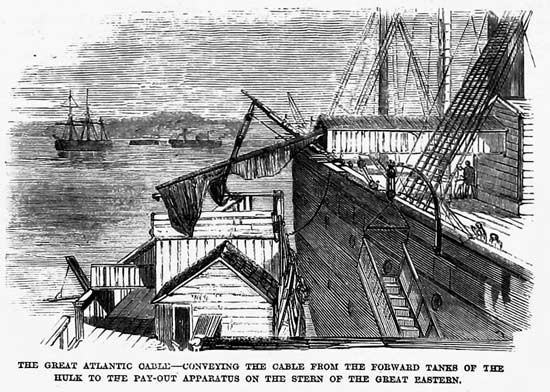

The Great Atlantic Cable—Conveying the Cable from the Forward Tanks of the Hulk to the Pay-Out Apparatus on the Stern of the Great Eastern |

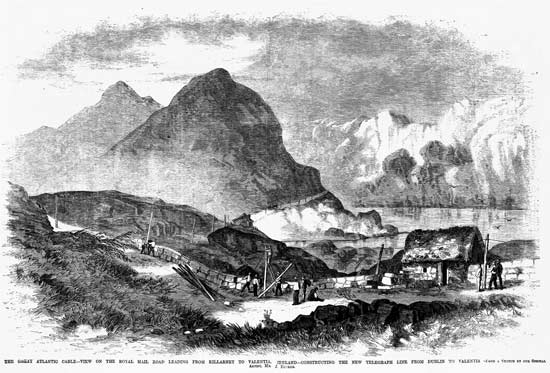

The Great Atlantic Cable—View on the Royal Mail Road leading from Killarney to Valentia, Ireland—Constructing the New Telegraph Line from Dublin to Valentia

From a Sketch by our Special Artist, Mr. J. Becker [original below]

Original Becker sketch TAC-JB-GB-6-4-65

Courtesy of the Becker Collection, Boston MA |

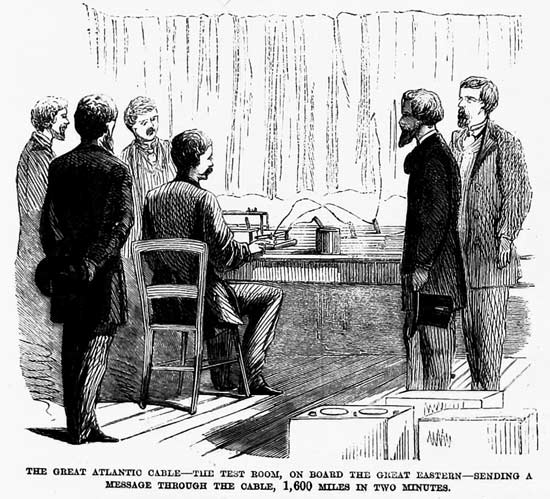

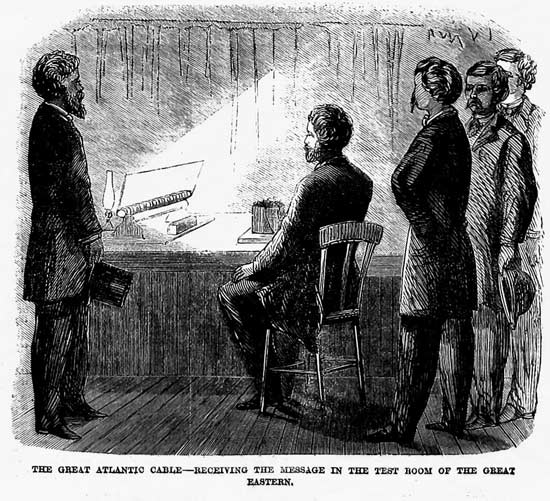

| The two following images must be either speculative or copied from the English press, as Joseph Becker, together with many other correspondents, had not been allowed on board Great Eastern. They are not credited to Becker. |

The Great Atlantic Cable—The Test Room on Board the Great Eastern—Sending a Message through the Cable, 1,600 Miles in Two Minutes |

The Great Atlantic Cable—Receiving the Message in the Test Room of the Great Eastern. |

26 August 1865

The Atlantic Cable.

The unpleasant intelligence of the probable failure of the Atlantic cable has reached us, and again the world is disappointed; for all men, of every nation, were either directly or indirectly interested in the success of the enterprise. The last news from the steamship Great Eastern is received through the English papers of the 4th August. They report that on the 2d, 1,200 miles of cable had been payed out, when the signals became unintelligible. How this news was received through the line (and it could apparently have been received in no other way) is not very clear. It is probably only a conjecture made by the electricians at Foilhommerum cliff, and so telegraphed to the English journals as an explanation of the inevitable silence.

We learn from Valentia Bay, under date August 4, that no communication has been had with the ship since, and no information received. The cause was unknown, and at the closing of this summary nothing additional had transpired. The land lines between Valentia had been out of order.

The London Times infers that the disaster occurred after the cable left the vessel, from the fact that it was unknown to those on board, who were signalling their messages as usual, when their signals became unintelligible at Valentia, and at last ceased entirely. As to the chances of recovering the impaired part of the cable and repairing it, it may be said that this process could not be accomplished at the rate of more than a quarter of a mile an hour, which the slightest wind or rough sea would at once put an end to. For such eventualities the Great Eastern is amply provided. She has several buoys on board, equal altogether to a weight of fifty tons, and she has at least five miles of powerful wire buoy ropes, which can support all that the buoys themselves can float. This effort to buoy, however, will not be resorted to till the last extremity, owing to the danger and improbability of finding the cable again.

The Times, in conclusion, remarks that if the Great Eastern is making successful efforts to haul in the cable and repair it, a clear renewal of the signals may be looked for in a couple of days. If, on the contrary, that time should pass without the cable giving signals of life, we fear the case must be considered hopeless as far as regards success this year.

The following is the latest dispatch received at Londonderry, from London, on the 4th inst.:

London, Friday, Aug. 4.

Communication with the Great Eastern remains suspended. Nothing has been heard from her since noon of the 2d instant.

There is still hope, however, that the great Atlantic telegraph cable may yet prove a success, for it is possible that although insulation ceased alter twelve hundred miles of the line had been successfully laid, still, the cessation of the electric current may have been the result of accident, which can be repaired, if the exact spot at which insulation ceased be known. It is not improbable that the cable was damaged by the paying-out machinery, as was the case with the first in 1858. If such be the case, and the line be not entirely broken, it can be easily pulled up, carefully spliced, and the work go on to successful completion. But it cannot be denied that the general interpretation of the news has created a feeling of deep regret and disappointment. It seemed the hopeful feeling we have so long indulged could not but be the precursor of success, and even to be compelled to indulge in a doubt, is painful. Although there is a cloud over the enterprise at present, it is not impossible the sky will yet be clear, and that in our next issue we may have the pleasure of announcing that the Great Eastern was delayed on the ocean to repair an injury which excited the present apprehensions, but which being repaired, the vessel sped on to the successful lauding of the cable on our shores.

26 August 1865

For some motive, it is impossible to conceive what one, the contractors for the great Atlantic Telegraphic Cable, rigorously refused to permit reporters aboard the Great Eastern. Perhaps they were determined to tell their own story—and if the latest intelligence from the cable be true, it will be a sorry one—in their own way. We had supposed the days of such narrowness and intolerance were past. It seems, however, the design of the contractors, whatever it was, came very nearly being frustrated by an “able” reporter who went on board as an assistant electrician. It is said he was not merely the special correspondent of a daily London paper, but had engaged to supply two weekly journals, the one with pictorial and the other with descriptive matter. The startling news was telegraphed by the secretary of the company to Mr. Glass, who sent out a letter by a special steamer with orders that the correspondent should be sent back. These were carried out with such promptitude, that there was no time for packing, and despite. argument and expostulation, this luckless writer was put on board one of the last boats leaving the big ship, while his bag and baggage was left on board. Altogether the business was a very small one on the part of the contractors, who may be assured, however, that there are busy pens and pencils on board the steamer, as they will soon have reason to know.

9 September 1865

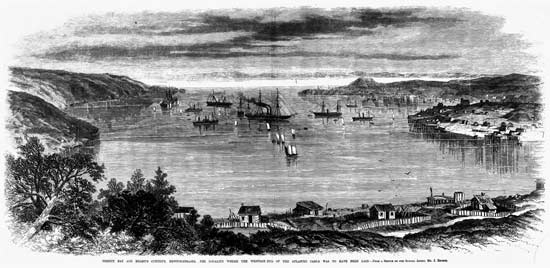

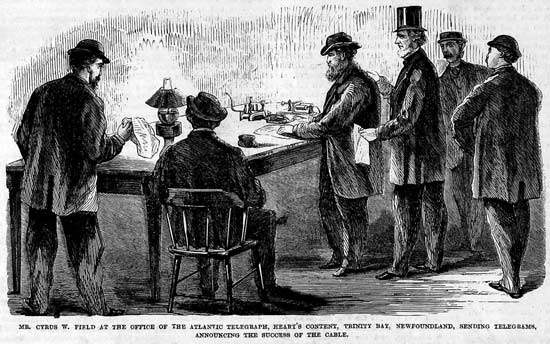

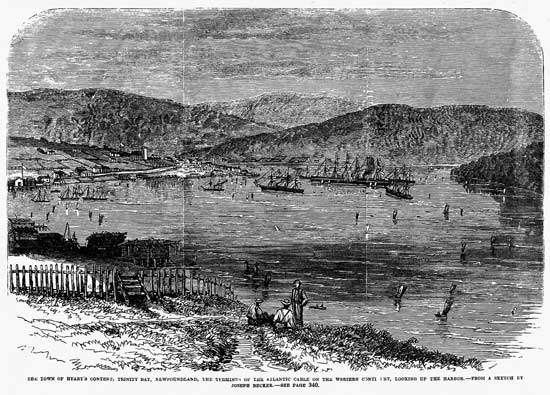

TRINITY BAY AND HEART’S CONTENT.

Trinity Bay and Heart’s Content, N.F., have been made celebrated as the proposed terminus of the Atlantic Cable, We give in the present number illustrations of the locality where, had not the attempt to span the ocean proved a failure, the first news of success would have been hailed on this continent. Trinity Bay can hardly be considered a desirable harbor, and Heart’s Content only aspires to the dimensions of a small fisherman’s village.

Trinity Bay and Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, the Locality where the Western End of the Atlantic Cable was to have been Laid.

From a Sketch by our Special Artist, Mr. J. Becker

|

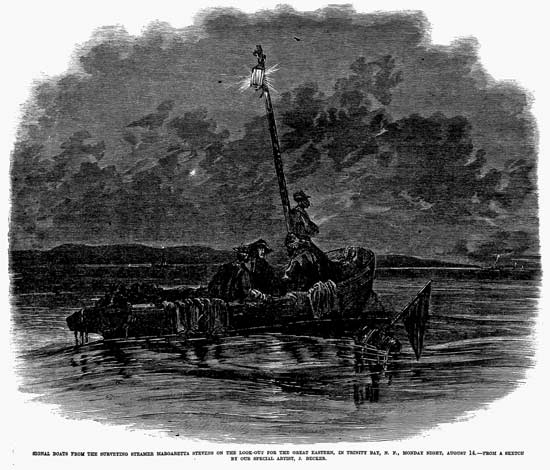

16 September 1865

SIGNAL BOATS AT HEART’S CONTENT.

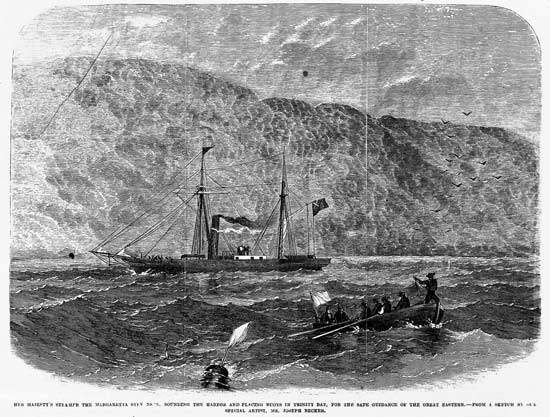

On the 14th of August, the day on which it was thought the Great Eastern would appear off Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, bearing the shore end of the Atlantic Cable, boats were sent from the surveying steamer Marguaretha to signal her approach. How long and anxiously hundreds of expectant people waited for the news of the arrival of the “the big ship,” we have already recorded. How sad was the disappointment when it was announced the Great Eastern had returned to England, and that the cable was a failure, the world knows. Still all the incidents connected with the great enterprise are of interest to the public, and in deference to that interest we give a view this week of the signal boats, as they appeared, at night, in Trinity Bay, off the harbor of Heart’s Content.

Signal Boats from the Surveying Steamer Margaretta Stevens on the Look-Out for the Great Eastern, in Trinity Bay, N.F., Monday Night, August 14.

From a Sketch by our Special Artist, Mr. J. Becker |

23 September 1865

The Great Eastern safely arrived at Sheerness on August 20. On the next day, the several boards of the companies interested in the Atlantic Telegraph Cable held meetings to consider their position under the temporary disappointment which has occurred. It was resolved to take immediate and energetic action not only to complete during next spring the laying of the present cable, but to submerge another by its side.

23 September 1865

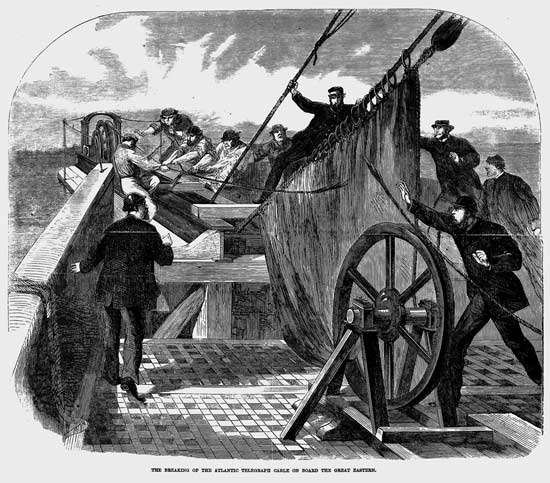

THE BREAKING OF THE ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH CABLE.

We transfer to our paper to-day Mr. Dudley’s sketch of that “sad and memorable” minute when the hopes of two worlds were “snapt” like the slender cable on which those hopes hung. In his diary of the 2d of July [actually August], the day of the disaster, Mr. Russell says: “The cable and wire rope together were now coming in over the bows in the groove in the layer wheel, the cable being wound upon a drum behind by the machinery which was once more in motion, and the wire rope being taken in round the capstan. But the rope and the cable were not coming up in a right line, but were hauled in with a great strain

on them, as were shown on the dynamometer to be very high, but not near breaking point. At last up came the cable and wire rope slacking together on the V wheel the bow. They were wound round on it, slowly, and were passing over the wheel together, the first damaged part being on board, when a jar was given to the dynamometer which flew up from 60 cwt., the highest point marked, with a sudden jerk 3½ inch. In fact, the chain shackle and wire rope clambered, as it were, up out of the groove on the right hand side of the of the wheel, got on the top of the rim of the V wheel, and rushed down with a crash on the smaller wheel, giving no doubt, a severe shock to the cable to which it was attached. The machinery was still in motion, the cable and the rope traveled aft together, the one towards the capstan, the other towards the drum, when just as the cable reached the dynamometer it parted 30 feet from the bow, and with one bound leaped, as it were into the sea.

“It is not possible,” continues Mr. Russell, “for any words to portray the dismay with which the sight was witnessed, and the news heard. It was enough to move one to tears, and when a man came aft with the inner end still lashed to the chain, and we saw the tortured strands, torn wires, and lacerated core, it is no exaggeration to say, that a strange feeling of pity, as though from some sentient creature mutilated and dragged asunder by brutal force, passed through the hearts of all. The precise spot where this accident occurred was lat. 51. 25; long. 39. 6; 1,186 miles of cable had been payed out; distance from Valentia, 1,062 miles; and from Hearts Content, 606 miles.”

The Breaking of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable on Board the Great Eastern |

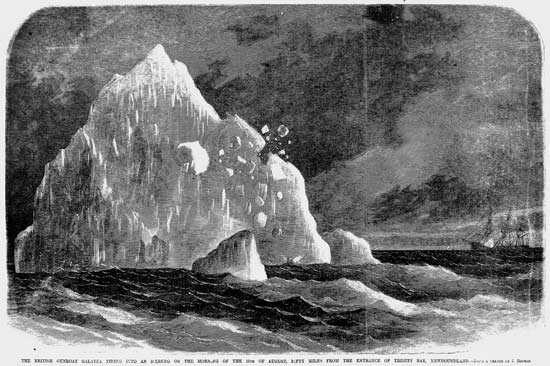

30 September 1865

THE BRITISH WAR STEAMER GALATEA,

Practicing Target Firing at an Iceberg.

Our Artist has given a very striking sketch

of an incident he witnessed on board H.B.M. steamship the Galatea, while it was waiting on this side of the Atlantic for the arrival of the Great Eastern with the Atlantic Cable—and we take this opportunity of thanking the officers of that noble war steamer, the Galatea, for their courtesy to him. In order to be all ready for the monster steamer, the steam of the Galatea was

kept almost constantly up, and about the first week in August she proceeded to sea, and dropped anchor about 60 miles out, in 100 fathoms of water. Now and then she would trip her anchor, and run out to the eastward to see if she could discover anything of the great vessel, that carried the hopes of so many people connected with that costly experiment.

On the 10th of August, as they were steaming along at an easy rate, an iceberg came in sight, which was considered a good opportunity for target practice. When the Galatea got within about a mile she commenced firing with round shot, but without producing any perceptible effect. Shell was then tried, and with the most marked results; for when the shell struck, it seemed to burrow in the iceberg, and, as it exploded, masses of fractured ice flew up into the air, like brilliant jets sparkling in the sun, and then falling down in a shower of crystals. The officers told our Artist that the height of the iceberg was about 100 feet, which gives its extreme altitude from the root to the crown, as 800 feet. So large were the masses detached from the berg by the shell firing, that it lurched first over on one side and then upon another, till after oscillating it regained its equilibrium.

The British Gunboat Galatea Firing into an Iceberg on the Morning of the 10th of August, Fifty Miles from the Entrance of Trinity Bay, Newfoundland.

From a Sketch by J. Becker |

24 February 1866

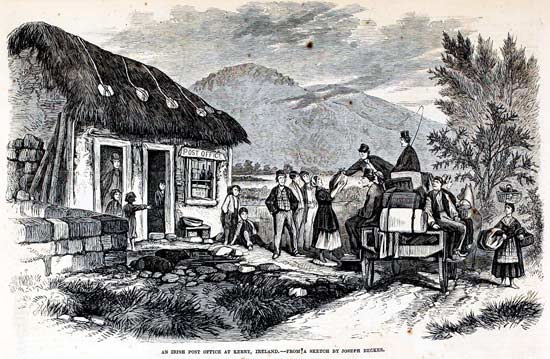

AN IRISH POST OFFICE IN KILLARNEY

We give, this week, another of the

sketches taken by our special Artist, who went to Valencia Bay to sketch the laying of the Atlantic cable. The scene is a few miles from the town of Killarney, on the road to Cahirciveen. To all the country round the Post Office is a spot of wonderful interest, and about its mud walls, and under its thatch, gathers all the village gossip. The arrival of the American mail is a matter of especial interest, and then comes those who have relatives in every part of this great country, to get letters, or hear those of others read, perhaps to got the remittances of money that aid them in joining the ones they love best on earth.

The Post Office everywhere is a spot of great interest, but the Irish Post Office is especially so, from the fact of its intimate connection with this country, and that through it many of the people get the pittance which will keep them from starvation, sent, perhaps, by some hard-working relative in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

An Irish Post Office at Kerry, Ireland

From a Sketch by Joseph Becker [original below] |

Although made at the same time as Becker’s other views of Valentia, this view of the mail arriving from America was not published until 24 February 1866.

The caption reads: “Scene in Kerry. An Irish post office arrival of the American Mail.”

Original Becker sketch TAC-JB-GB-65-1

Courtesy of the Becker Collection, Boston MA |

In July 1866 Great Eastern set sale from Ireland on a second expedition to lay the Atlantic cable. After the successful landing of the cable at Newfoundland on 27 July, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper devoted several pages of its issue of 18 August 1866 to the story, including two full-page illustrations and a number of smaller images, many credited to Joseph Becker. Some of these had been published in 1865 and were re-used as if they had been made during the 1866 expedition.

Joseph Becker related the story of his 1865 experiences in an article written on his retirement in 1905 and published in Leslie’s Weekly on December 14th that year:

After the close of the great conflict I was dispatched to London to depict scenes connected with the laying of the Atlantic cable. The cable was to be taken out on the steamer Great Eastern, and I hoped to be a passenger on the vessel when she sailed for Newfoundland, paying out the cable on the way. But the managers of the company refused passage to all artists and correspondents, and I made my way otherwise to Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, where the American end of the submarine telegraph was to be landed. It was an out-of-the-way locality. Some thirty other artists and writers also assembled there. The Great Eastern was looked for at any hour, but she failed to appear. For thirty-eight days we were marooned in that forsaken place, with only rude accommodations and meagre fare. We grew utterly disgusted, wearied, and ennuied long before a sailing-vessel stole into the bay and notified us that the laying of the cable had been deferred. We lost no time after that in departing for civilization. My fellow-artists had refrained from making sketches at Heart’s Content. But I had made drawings of the bay, the coast and hamlet, and so when, a year later, the Great Eastern actually dropped the cable on Heart’s Content beach, FRANK LESLIE’S was the only paper which published illustrations of the locality.

18 August 1866

THE ATLANTIC CABLE.

These two images were on the front page of the issue, with the story beginning a few pages later.

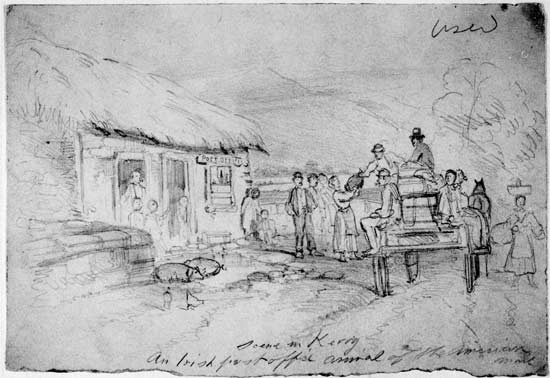

Mr Cyrus W. Field at the Office of the Atlantic Telegraph, Heart’s Content, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, Sending Telegrams, Announcing the Success of the Cable |

The Town of Heart’s Content, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, the Terminus of the Atlantic Cable on the Western Continent, Looking up the Harbor.—From a Sketch by Joseph Becker |

The great event of the age is the successful laying of the ocean telegraph, by which two continents are brought into instant communication and bound together by a multitude of ties. Whether regarded as a triumph of scientific skill, as a monument of enterprise and faith in human capability, or an evidence of persevering determination to overcome the most discouraging obstacles, this event will ever hold a prominent place in the world’s history, and exercise an important influence over the world’s progress.

In view of the absorbing interest of this successful undertaking, we devote a considerable portion of our paper, this week, to the illustration of various points and features, connected with the great ocean cable.

The first successful submarine telegraph was laid between England and France, a distance of twenty-four miles, in 1850, since which time a number of lines have been laid and satisfactorily operated. No one then dreamed of an Atlantic Cable, and in the development of electrical science then existing, such a dream would have proved wholly illusory. Experiments, however, soon demonstrated the fact, that, under certain conditions, currents of electricity could be sent through submerged wires for any distance, and also showed how certain scientific difficulties attending their transmission could be obviated or removed. These facts established, the way for an ocean telegraph was fairly open, and all required was the genius to plan, and the energy and capital to execute. These were happily found, and through the efforts of Mr. Field, who had devoted a large share of attention to the subject, a company was formed in 1854 for the purpose of connecting the Old and New World, with an ocean telegraph. In 1858 the cable was stretched across the Atlantic from Ireland to Newfoundland; messages were transmitted, and for a few days everything promised success, when, from some unknown cause, the wire ceased to convey signals, and the project proved a failure. But the possibility and feasibility of the scheme were now demonstrated. Only its details required attention, and it was confidently believed that science and skill could overcome the difficulties in the way of success, and that the actual working of such a line was only a question of time.

It is needless to say how unhappily the expedition of last year failed, and to this day it is not known whether the injury to the cable’s insulation was caused by accident or wanton mischief. The commercial loss upon these failures has been great, but even out of the evil has come some good, for in the interim the science of making, testing and laying cables has so much improved, that an undetected fault in an insulated wire has now become literally impossible, while so much are the instruments for signaling improved, that not only can a slight fault be disregarded, if necessary, but it is even easy to work through a submarine wire with a foot of its copper conductor stripped and bare to the water. This latter result, astonishing as it may appear, was actually achieved for some days with the whole Atlantic Cable on board the Great Eastern. Out of a length of more than 1,700 miles, a coil was taken from its centre, the copper conductor stripped clean of its insulation for a foot in length, and in this condition lowered over the vessel’s side till it rested on the ground. Yet, through this the clearest signals were sent.

The faith of the gentlemen connected with this wonderful enterprise in its ultimate triumph never for a moment wavered; if they met with disaster and disappointment, they were only more careful in avoiding mistakes and more earnest in prosecuting their work. A new cable having been constructed and placed, on the Great Eastern, a connection was made with the shore end, at Valentia, on July 15th, and the steamer at once started on her westward voyage, reaching Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, on the 27th, making an average speed of about five miles per hour.

Full Size Diagram of the Atlantic Cable Just Laid |

During the whole voyage, constant communication was kept up with the shore end of the cable, and no intermission of signals was experienced, while daily news from Europe was posted up outside the telegraph office on board the Great Eastern. Immediately on the arrival of the steamer at Heart’s Content, Mr. Field announced the success of the undertaking to the directors of the company in this city, and shortly afterward sent a congratulatory message to President .Johnson. Heart’s Content, the American terminus of the cable, is a little fishing hamlet, hitherto unknown, but destined to become a place of importance, as one of the main points in the history of the age.

The bay on which it is situated is a very safe and capacious one, and on this account was selected. On our first page we give a sketch of the town and harbor. The eastern terminus of the cable is at Knightstown, Ireland, a few miles distant from the point previously chosen for the shore end. Like Heart’s Content it has no intrinsic importance, but will hereafter become famous.

This illustration was originally published in the issue of 15 July 1865 with a somewhat different caption.

Knightstown, Valentia, Ireland, the Terminus of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable |

On the 7th of July the end of the Irish shore cable was landed from the vessel selected for that purpose and early the next morning the laying was successfully completed, and the end buried in ninety-four fathoms of water, and its position indicated by a buoy, at a distance of twenty-seven miles from land. At this point, the Great Eastern effected a connection with the portion of the cable already laid, and proceeded on her voyage. On page 340 we give a view of Knightstown, and also of the reception of the cable on board the Great Eastern.

This illustration was originally published in the issue of 12 August 1865 with a somewhat different caption. Other illustrations reprinted from that issue include views of the cables of 1858 and 1865, and the two scenes in the test room on board Great Eastern. These may be viewed under that date in the 1865 section of this page and are not repeated here.

The Steamship Great Eastern off Sheerness, England, Receiving the Atlantic Cable on Board from the Hulk |

That there might be no delay when the telegraph fleet should arrive at its destination, a steamer was dispatched to make soundings and station buoys in the harbor on this side. Thus every precaution was takes to insure success and facilitate the operations of the enterprise.

Her Majesty’s Steamer the Margaretta Stevenson, Sounding the Harbor and Placing Buoys in Trinity Bay for the Safe Guidance of the Great Eastern.—From a Sketch by our Special Artist, Mr. Joseph Becker |

As already stated, tests were continually applied while the ship was paying out the cable, and an unceasing communication kept up with the office on the other side. The fact that there was no interruption in the signals augured well for the success that has been achieved, and was a great encouragement to Mr. Field and his associates, who watched the progress of their great undertaking with the most intense solicitude. On this page there is a view of the test-room on the Great Eastern, and a diagram of the three cables that have been laid. These are all similar in their construction, each consisting of a conductor composed of a copper strand of seven wires (six laid around one), an insulator of gutta percha, and an external protection of iron wire surrounded with a preserving medium. The present cable is somewhat stronger and heavier than either of the others, has been more carefully and scientifically constructed, and gives promise of more satisfactory working.

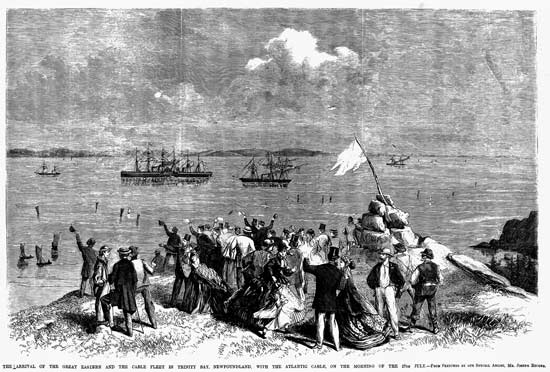

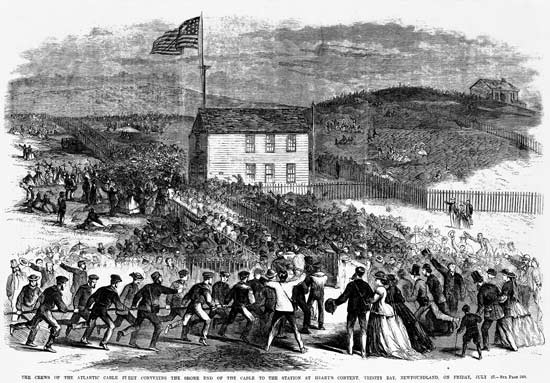

Our double-page illustrations represent the arrival of the Great Eastern at Trinity Bay and the carrying the shore end of the cable to the station at Heart’s Content.

The Arrival of the Great Eastern and the Cable Fleet in Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, with the Atlantic Cable on the Morning of the 27th July.—From Sketches by our Special Artist, Mr. Joseph Becker |

The Crews of the Atlantic Cable Fleet Conveying the Shore End of the Cable to the Station at Heart’s Content, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland, on Friday, July 27 |

Thus the grand conception of establishing telegraphic communication across the ocean has been realized, and, as if in token of the benefits the world will derive from it, the first intelligence conveyed was of peace between the contending Powers of Europe.

One final sketch from Newfoundland by Joseph Becker was published the following week, although it was not directly related to the cable.

25 August 1866

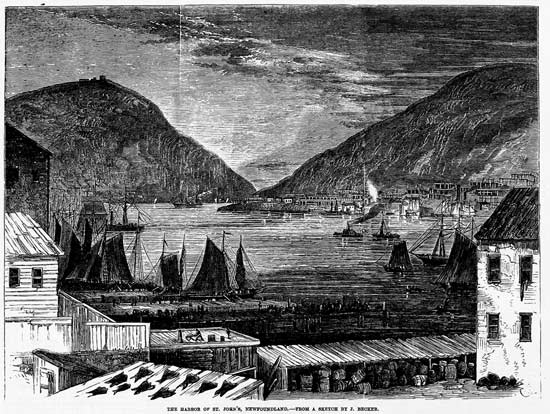

THE HARBOR OF ST. JOHN’S, NEWFOUNDLAND.

On this page we give a fine view of the harbor of St. John’s, a town of very considerable importance to the fishing interests. The harbor is spacious, and sheltered on all sides by high hills protecting it from the fierce storms of the Atlantic, so that there is always a safe and commodious anchorage. The place is quite strongly fortified; in fact, its position is a defense, and it needed but little expenditure to render it secure from any ordinary assault.

The town lies along the north side of the port, consisting mainly of one street. There are a few handsome and well-built edifices, but most of the houses are of wood, and, in consequence, the place has frequently suffered severely from extensive fires. The population of St. John’s is about 25,000.

The Harbor of St. John’s, Newfoundland.—From a Sketch by J. Becker

The original sketch of this illustration at the Becker Collection is dated 1865, so although not published until 1866 it was presumably made when Becker was in Newfoundland the previous year awaiting the arrival of Great Eastern. |

References:

The Becker Collection website (accessed 27 October 2018)

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper Volumes 19 & 20, 1864-65

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper Volumes 21 & 22, 1865-66

See also the coverage in Leslie’s of the 1858 Atlantic cable expedition

Return to the Atlantic Cables index page |