France laid its first submarine cable across the Atlantic in 1869, from the cove of Petit Minou (about 10km west of Brest on the French mainland) to

Saint-Pierre et Miquelon (off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada), with an extension to

Duxbury, Massachusetts. The cable was made and largely financed in Britain, and after some early rate competition the French company was taken over by the Anglo-American Telegraph Company in 1873.

There was a certain amount of politics and underhanded business dealings in arranging the landing of the cable in the United States against the monopoly of the Anglo-American company, which James Scrymser describes in his 1915 autobiography.

Duxbury was incorporated in 1637. Situated 33 miles

south of Boston and 246 miles from New York City, the town is set at the

head of Plymouth Bay “in a lovely undulating landscape washed by

a beautiful sheet of water”[1]

A center of shipbuilding until the mid-nineteenth

century, when ships became too large for the shallow bay, Duxbury achieved

a measure of fame as the landing site for the third Atlantic Cable. This

1869 French cable was the beginning of the second period of long-distance

submarine cable laying, when the art had advanced beyond the experimental

and satisfactory results were likely. A contemporary review of the

decade of the 1860s illustrates this[2]:

| The

failure to lay down an Atlantic telegraph in the last previous decade

(1858) had indisposed men to undertakings so vast in every sense,

and so doubtful in every way. Some years passed before the attempt

was renewed, but the genius and energy of our countryman, Mr. Cyrus

W. Field, finally cleared all difficulties away, after repeated failures;

and in 1866 the Atlantic Telegraph became an accomplished fact, just

in time to furnish the news of the closing events of the Germano-Italian

war. A cable that had previously been lost was recovered, and two

lines thus existed between Europe and America.

In

1869 the French cable was laid, connecting Brest with Duxbury (Massachusetts).

The great problem had been solved in 1866, and for more than four

years daily communication between the Old World and the New has

taken place. The telegraph has been extended to India, and there

is now communication through its existence between San Francisco

and Calcutta.

These

great enterprises all belong to the seventh decade of the century;

and others are in progress which will bring India in connection

with Australia, and the extremities of Eastern Asia with those of

Western America.

|

Julius Reuter, of the famous news agency,

and Baron Emil d’Erlanger, backed by British financiers, were the promoters of La Société du Câble

Transatlantique Française.

|

|

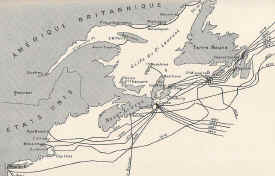

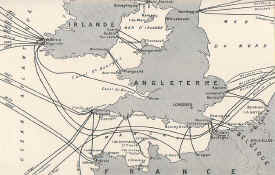

| These cable

maps, published by the International Telegraph Bureau, Bern, in 1897,

show the 1869 cable route from Brest to St. Pierre & Miquelon,

continuing to Sydney and Duxbury. The maps also show eleven

further transatlantic cables laid between 1869 and 1897, evidence

of the rapid development of the cable network in the three decades

following the laying of the French cable[3]. |

The contract to manufacture

and lay the cable was given to Telcon, the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance

Company, of London. Telcon manufactured the Brest to St. Pierre section

of the cable, and subcontracted W.T. Henley to make the St. Pierre to

Sydney length.

|

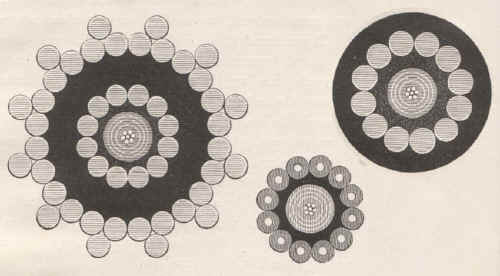

The illustration shows the three weights

of cable used for the main run of 2584nm from Brest to St. Pierre. All had an identical core of 7 copper strands. On the left is the shore-end cable, armoured with 12 No. 7 BWG and 12 strands of 3 No. 4½ to resist damage from rocks and ships’ anchors. On the right is the intermediate cable, 12 No. 4 BWG, used to run from the shallows near shore out to deeper water. In the center is the deep-sea cable, the main length of the run, which has the lightest armouring of 12 No. 13 BWG each wrapped in 5 strands tanned manilla.

The diagrams are to scale; the

deep-sea cable is about 1" diameter and is similar to that used on the 1866 Atlantic cable, but with twelve armouring wires rather than the ten of the 1866 cable.

Deep sea cable mounted sample.

The engraved mounts at each end of the cable are shown below. |

Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Compy Limited

Contractors, London

Société du Câble

Transatlantique Française Limited

Brest to New York 1869

Deep Sea Cable

|

Oddly, the cable route of this section is is given as “Brest to New York”, and this section has ten armouring wires rather than the twelve shown in the diagram above.

This section is identical to a recovered piece of this cable in the Science Museum (London) Making of the Modern World gallery, where it is described as “...laid by the Great Eastern in 1869.” An end view of the Science Museum cable showing the ten armouring wires may be seen on the Recovered Cables page. |

| The 749nm run from Saint Pierre to Duxbury also used a 7-strand copper conductor, but was made by W.T. Henley Telegraph Works Company and had different armouring from the transatlantic cable. The main cable had 10 No. 8 BWG, intermediate 12 No. 4 BWG, shore ends 10 No. 8 BWG plus 12 strands 3 No. 4½ BWG. |

|

St Pierre to Duxbury main cable

Images courtesy of the Ladd Observatory collection at Brown University.

Photographer Dave Fischer. |

The main cable was laid by Great Eastern with CS Chiltern and CS Scanderia. CS Hawk laid the European shore end

and CS William

Cory laid and landed the Sydney and Duxbury extensions[4].

|

1885 map of Duxbury showing the cable

station

and the cable laid across the marsh

|

The Great Eastern had bankrupted

a series of owners, but had successfully laid the 1866 cable from Ireland

to Newfoundland. After this, though, the ship languished for lack of work.

This article appeared in Scientific American in April 1868[5]:

| An

“Elephant” Indeed

The owners

of the Great Eastern, mourning not simply a non-appearance of dividends,

but a very heavy expense in keeping the big ship in existence, are

in a sad state of perplexity, not knowing what is to become of their

unproductive property. At the late annual meeting of the shareholders,

the directors’ report deplored the failure of the company to complete

its contract with the new French cable company, the latter refusing

to act up to the terms of the agreement, and the whole affair is

now before the law courts for adjudication. As far as the future

was concerned, the chairman tried to persuade the company that the

prospects were encouraging as there were other cables to be laid

and he was certain that their ship was the only one which could

accomplish such an undertaking successfully. One hopeful proprietor

suggested that the Leviathan should he converted into an immense

floating hotel, but the plan was promptly voted down. The shareholders

are certainly deserving of public sympathy.

|

The difficulty with the French cable company was apparently resolved,

as just over a year later, on 17 July 1869, Scientific American

reported[6]:

| The

work of constructing the telegraph line from Boston to Duxbury, Mass.,

to connect with the new French cable, was begun on the 19th of June. |

British engineer Fleeming Jenkin noted in his memoirs[7]:

| JUNE

17, 1869. - Here are the names of our staff in whom I expect you to

be interested, as future GREAT EASTERN stories may be full of them:

Theophilus Smith, a man of Latimer Clark’s; Leslie C. Hill, my prizeman

at University College; Lord Sackville Cecil; King, one of the Thomsonian

Kings; Laws, goes for Willoughby Smith, who will also be on board;

Varley, Clark, and Sir James Anderson make up the sum of all you know

anything of. A Captain Halpin commands the big ship. There are four

smaller vessels. The WM. CORY, which laid the Norderney cable, has

already gone to St. Pierre to lay the shore ends. The HAWK and CHILTERN

have gone to Brest to lay shore ends. The HAWK and SCANDERIA go with

us across the Atlantic and we shall at St. Pierre be transhipped into

one or the other.

JUNE 18. SOMEWHERE

IN LONDON. - The shore end is laid, as you may have seen, and we

are all under pressing orders to march, so we start from London

to-night at 5.10.

June 20. OFF

USHANT. - I am getting quite fond of the big ship. Yesterday morning

in the quiet sunlight, she turned so slowly and lazily in the great

harbour at Portland, and bye and bye slipped out past the long pier

with so little stir, that I could hardly believe we were really

off. No men drunk, no women crying, no singing or swearing, no confusion

or bustle on deck - nobody apparently aware that they had anything

to do. The look of the thing was that the ship had been spoken to

civilly and had kindly undertaken to do everything that was necessary

without any further interference. I have a nice cabin with plenty

of room for my legs in my berth and have slept two nights like a

top. Then we have the ladies’ cabin set apart as an engineer’s office,

and I think this decidedly the nicest place in the ship: 35 ft.

x 20 ft. broad - four tables, three great mirrors, plenty of air

and no heat from the funnels which spoil the great dining-room.

I saw a whole library of books on the walls when here last, and

this made me less anxious to provide light literature; but alas,

to-day I find that they are every one bibles or prayer-books. Now

one cannot read many hundred bibles. . . . As for the motion of

the ship it is not very much, but ’twill suffice. Thomson shook

hands and wished me well. I DO like Thomson. . . . Tell Austin that

the GREAT EASTERN has six masts and four funnels. When I get back

I will make a little model of her for all the chicks and pay out

cotton reels. . .

Here we are

at 4.20 at Brest. We leave probably to-morrow morning.

JULY 12. GREAT

EASTERN. - Here as I write we run our last course for the buoy at

the St. Pierre shore end. It blows and lightens, and our good ship

rolls, and buoys are hard to find; but we must soon now finish our

work, and then this letter will start for home. . . . Yesterday

we were mournfully groping our way through the wet grey fog, not

at all sure where we were, with one consort lost and the other faintly

answering the roar of our great whistle through the mist. As to

the ship which was to meet us, and pioneer us up the deep channel,

we did not know if we should come within twenty miles of her; when

suddenly up went the fog, out came the sun, and there, straight

ahead, was the WM. CORY, our pioneer, and a little dancing boat,

the GULNARE, sending signals of welcome with many-coloured flags.

Since then we have been steaming in a grand procession; but now

at 2 A.M. the fog has fallen, and the great roaring whistle calls

up the distant answering notes all around us. Shall we, or shall

we not find the buoy?

JULY 13. -

All yesterday we lay in the damp dripping fog, with whistles all

round and guns firing so that we might not bump up against one another.

This little delay has let us get our reports into tolerable order.

We are now at 7 o’clock getting the cable end again, with the main

cable buoy close to us.’

A TELEGRAM

OF JULY 20: I have received your four welcome letters. The Americans

are charming people. |

|

|

The Great Eastern Steam-Ship Leaving

Sheerness

With The French Atlantic Cable.

The Illustrated London News, June 26, 1869 |

Willoughby Smith, in his book “The

Rise and Extension of Submarine Telegraphy”[8] gives a detailed account of the cable laying by Great Eastern,

the voyage beginning off the coast of France on 21 June 1869. The

ship was captained by Robert Halpin, and on board was an assemblage

of many famous cable men, including Sir James Anderson (captain of

the Great Eastern on its previous Atlantic Cable voyages),

Sir Daniel Gooch, Willoughby Smith, Latimer Clark, Fleeming Jenkin,

and C.F. Varley, among others. William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) was at

the cable station in Brest making measurements between ship and shore

as the cable was laid.

The cable was landed at St. Pierre, off the coast of

Newfoundland, on 13 July 1869. This was the end of Great Eastern’s

involvement in this cable, but not the end of the cable. From St. Pierre

two cables were run: one to Sydney, Nova Scotia, the other to Duxbury.

Smith was unwell, and went back to England on Great

Eastern, but he reports the landing of the cable in Duxbury. The

ships involved in this last part of the expedition were the Chiltern,

Scanderia, and William

Cory:

| Friday,

July 23rd. The deep sea portion of the cable was completed off Cape

Cod at 11.20 a.m. The splice was then made between deep sea and intermediate

portions, and at 12.45 we commenced paying out again.

After paying

out the thirty-one knots of intermediate cable we commenced on the

heavy shore end (4.45 p.m.), and at 6.30 we had arrived at our anchorage

opposite the landing place. The hands at once commenced to coil

the end into a boat, and in about three hours the end was conducted

into the cable house on shore.

|

Photographer Martin Chandler recorded the cable landing in a set

of stereoviews, some of which are illustrated in this article. Chandler’s

business location is listed on the back of the cards as Marshfield, Massachusetts,

immediately to the north of Duxbury.

Listed initially as a daguerreian, Chandler later

took stereo views, and remained in business in Marshfield until 1896.

According to information received in May

2003 from Harry Chandler (Martin’s brother’s great-great-grandson), Martin

Chandler died in Marshfeld in 1897. The Marshfield Historical Commission

has many of Chandler’s photographs (including one of his wagon and photographic

equipment) and reprints of his photographs hang in the Marshfield Town

Hall.

On 7 August 1869, Scientific American reported

the successful completion of the cable[9]:

| The

French Cable Laid

The French

Atlantic Cable has been successfully laid, making in all, three

cables which have been stretched between the Eastern and Western

hemispheres. The Great Eastern has proved herself especially useful

in the laying of long cables, and should she now be laid up forever,

her history will always be connected with that of the most remarkable

enterprises ever undertaken and completed. The efficiency of submarine

cables, and their immunity from interruption through the effect

of atmospheric electricity suggests the expediency of connecting

all large sea ports by cables instead of land lines.

|

On that same date the Société du Câble

Transatlantique Française placed a classified advertisement in The Times with their tariff:

| SOCIÉTÉ du CÂBLE TRANSATLANTIQUE FRANÇAISE (Limited).—French Atlantic Telegraph Company.

Notice.—The CABLE of the above Company will be OPENED to the public for Messages between Europe and America on and after Sunday, the 15th August.

Until further notice the tariff to be charged on a message between Great Britain or France and New York or Boston will be £1 12s. (40 francs) for 10 words and 3s. 3d. (4 francs) for each additional word.

Messages will be received at the office of the Submarine Telegraph Company, 58, Threadneedle-street, and at all London and provincial offices of the United Kingdom Telegraph Company (Limited).

N.B. Press messages will be taken at half the above rate.

ROBERT SLATER, Secretary

Bartholomew-house, London, August 2, 1869. |

Right underneath the French company’s ad was this one, showing the immediate effect on the British market of the opening of the French cable:

ANGLO-AMERICAN TELEGRAPH COMPANY (Limited).

Messages to America—Further REDUCTION OF TARIFF from the United Kingdom to New York, to commence August 10th, 1869. 30s. for 10 words and 3s. for each extra word.

Press messages will be transmitted at half the above rates.

Messages will be received at all the Stations of the Electric and International Telegraph Company and the British and Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company.

JOHN C. DEANE, Secretary

No. 25, Old Broad-street, London, Aug. 5, 1869. |

The French company was absorbed by Anglo-American in 1873.

The next month, on 25 September 1869, Scientific American printed

a report, extracted from the Boston Advertiser, of the visit

of members of the Scientific Association to the cable station at Duxbury,

which gives an interesting insight into the workings of the cable[10]:

| Mode

of Working the French Cable

A few of the

members of the Scientific Association, which closed its session

at Salem last week, have been making a visit to Duxbury, the terminus

of the newly laid French Cable. What they saw is pleasantly told

by the Boston Advertiser, from which we make the following extracts:

In an old but

well preserved clapboard mansion of that quaint old town were found

the headquarters of this new and wonderful highway. The visitors

were cordially welcomed by the manager, Mr. Brown, and were at once

brought into the presence of the flitting, flame-like image which

indicated, in symbols, on a graduated screen, the thoughts working

at that instant on the other side of the Atlantic. Interpreting

the fitful tremor of the image, or line of light, one inch in length,

and one eighth of an inch in breadth, the youthful interpreter,

who did not look the wizard that he was, calmly read, for transcription

by his assistant, a message in which occurred, at intervals, the

words ‘New Orleans’ - ‘Citizens’ - etc., etc. While inspecting the

apparatus the members of the party received the following message

fresh from France, sent expressly to them:

“To Duxbury,

from Brest - Time 5:20 P.M [Paris Time]

“The company present their compliments to the gentlemen assembled

at Boston, and hope to be able to send them news of the great international

boat race that will be gratifying to both nations.”

The usual rate

of transmission is about ten or twelve words per minute. Looking

for the mechanism by which these wonderful results were obtained,

the inquiring visitors observed, on their right, placed on a marble

pedestal, a medium-sized spool of silk-covered copper wire, said

to consist of several thousand turns or convolutions, in the center

of which spool, suspended by a single silkworm fiber, was a minute

mirror attached to a little magnet made from a piece of watch spring.

From a lamp, properly placed and shaded, a beam of light was thrown

upon this mirror, and from the mirror was reflected, two hundred

times enlarged, upon the graduated screen in front of the interpreter,

the flame-like image already mentioned. In transmitting, from Duxbury

to Brest, the operator, with his right hand, makes use of two keys

or springs, one of which, being pressed, causes, at Brest, a deflection

in a similar mirror, sending the image-flame to the right, while

pressing the other key deflects the mirror at Brest in the opposite

direction, sending the image to the left Its indications are thus

interpreted; a jerk or flitting once to the left and then once to

the right denotes the letter a; a flitting once to the right and

then three times to the left, denotes the letter b; and thus, letter

by letter, the words are spelled

Passing into

an adjoining room the delicate instruments used for testing the

electric conduction of the cable are shown among which are condensers

and batteries, rheostats and shunts, bridges, switches, and plugs,

and, crowning all, the wonderful astatic galvanometer of Sir William

Thompson. But possibly it would weary our readers to tell of ohms

and megohms, farads and megafarads, volts and microvolts, and all

the terminology of conduction, resistance, electrostatic capacity,

and continued electrification. It may, however, gratify them to

learn that the insulation of the deep-sea cable, between Brest and

St. Pierre, has more than doubled in efficacy during the short month

which has elapsed since this cable was first committed to the embraces

of Old Ocean - as is evinced by the fact that, soon after it was

laid, the insulation resistance rose to 2300 megohms, and has since

been gradually increasing until it is now 5000 megohms per nautical

mile. This improvement in the insulation of the deep-sea cable is

believed to be mainly due to the coldness or diminished temperature

to which it is subjected at great ocean depths. The insulation resistance

of the portion of the cable connecting Duxbury and St. Pierre is

much less, namely, 1500 megohms per nautical mile.

If one would

inquire of a cable electrician - what is a megohm? he might, with

propriety, be told that it is a million ohms. Should he still further

inquire - but what is an ohm? a suitable reply would be, it is the

yardstick of the electrician by which he measures the electric condition

of conductors, and which may be represented by a round wire of pure

copper one-twentieth of an inch in diameter and 240 feet in length,

at the temperature of 60 degrees of the Fahrenheit thermometer;

while a megohm, by which he measures the resistance of insulators,

is a unit, the length of which is a million times as great.

|

|

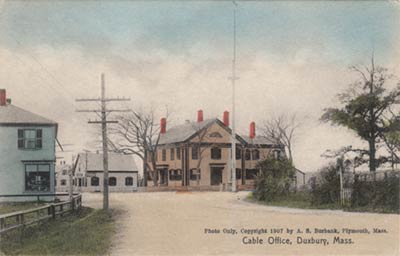

The Duxbury Cable Office on a 1907

postcard.

Detail of building |

Landing of the shore end of the French

Atlantic Telegraph cable at Minou, near Brest

[From a drawing by Robert Dudley, Illustrated London News, July 3, 1869] |

|

| References:

1. Benjamin,

S. G. W: Along the South Shore, Harper’s new monthly magazine./

Volume 57, Issue 337, June 1878:

“Duxbury immediately adjoins Kingston, at the head of Plymouth Bay,

admirably situated, beyond most towns in New England, in a lovely undulating

landscape washed by a beautiful sheet of water. Like almost every town

in Massachusetts, it derives its name from a spot in old England endeared

to the first settlers by many fond memories.

“In more recent times Duxbury has been noted for ship-building, and

its name has been carried to all parts of the world by some of the finest

and fleetest vessels that ever clove the sea waves and defied the storm.

In 1869 the landing of the French cable at Duxbury gave the little town

a novel interest.

“Marshfield immediately adjoins Duxhury on the north. It is a straggling

township, divided in to Marsbfleld, Marshfield Centre, East Marshfleld,

Sea View, Webster Place, Cut River, and Brant Rock, the whole scarcely

aggregating two thousand souls. The township was first settled by Edward

Winslow the third Governor of Plymouth Colony, in 1632. The place was

first called Green Harbor, then Wrexham by the Welsh whom Winslow brought

to this country, and eventually Marshfield.”

2. Hazewell,

C.C.: The Seventh Decade of the Nineteenth Century, Harper’s new

monthly magazine. / Volume 42, Issue 248, January 1871.

3. Bright,

Charles: Submarine Telegraphs, Their History, Construction and Working,

London. 1898.

4. Haigh,

K.R.: Cableships and Submarine Cables, London, 1968, Adlard Coles.

5. Scientific

American, New Series, Volume 18, Issue 14, New York, April 4, 1868.

6. Scientific

American, New Series, Volume 21, Issue 3, New York, July 17, 1869.

7. Stephenson,

Robert Louis: Memoir of Fleeming

Jenkin, 1887.

8. Smith,

Willoughby: The Rise and Extension of Submarine Telegraphy, London,

1891, J.S. Virtue & Co. Reprinted New York, 1974, Arno Press.

9. Scientific

American, New Series, Volume 21, Issue 6, New York, Aug 7, 1869.

10. Scientific

American, New Series, Volume 21, Issue 13, New York, Sept 25, 1869

See also:

The

landing of the French Atlantic Cable at Duxbury, Mass.: July, 1869,

Boston, 1869, A. Mudge & Son, Printers.

Hoyt, Franklin

Kaye:The French Atlantic Cable 1869, Duxbury 1982. Published by

the Duxbury Rural & Historical

Society and may be ordered through the Society’s website. Hoyt’s booklet

notes that he was given two bound volumes of the corporate records of

the Atlantic Telegraph Company of 1856, and the Anglo-American Telegraph

Company of 1866, and these volumes are now in the Society’s library.

The Duxbury Historical Society has a museum in the King Caesar House in Duxbury, with a sizeable

collection of equipment that was once used in the telegraph office. The

museum is open June through August, Wed-Sun 1-4 pm, and during September,

Sat-Sun 1-4 p.m.

The Society’s Drew Archival Library has a finding aid for its French Atlantic Cable Collection. A blog post gives more information.

Mahler,

Heinrich: Das franzosisch-amerikanische Kabel, Berlin, 1871,

8vo. 42pp, folding map.

Underwater

Cables in the Brest Harbor - a short History of French Trans-Atlantic

Telegraph Cables from the French Viewpoint (in English)

Article from Chambers’ Journal, London, reproduced by Scientific American |