|

Henry Clifford - Telegraph Engineer

Early Life

Henry

Clifford as a youth.

Clifford Family Album,

Hull Maritime Museum |

| |

Henry

Clifford’s 1838

apprenticeship indenture |

Henry Clifford (1821-1905) started his career as a mechanical engineer. Clifford, the cousin of Sir Charles Bright’s wife, is mentioned numerous times in the two-volume biography of Bright written by Bright’s brother and son and published in 1898. At the time the book was published Clifford had recently retired from a long and productive career in the cable industry.

Henry Clifford was born in Hull on 27 October 1821 to William Clifford and Alice Gill. He was baptised at Sculcoates All Saints on 14 November 1821.

[Sculcoates Parish Register 1821 p.27]

He had early ambitions to be an artist, but under family pressure, in 1838 at age 16 he was apprenticed to William Simpson & Company Engineers and Millwrights of Aberdeen “for learning the business of an Engineer,” the five year indenture running from 25 March 1839 to 25 March 1844. Henry’s father William Clifford paid Simpson a £50 premium for the apprenticeship, and along with his training Henry was entitled to receive “Bed Board and Clothes” as well as an allowance of four shillings per week the first year rising to nine shillings in the fifth year.

The 1841 Scottish census shows Henry Clifford at age 19 living in Aberdeen with the occupation of engineering apprentice.

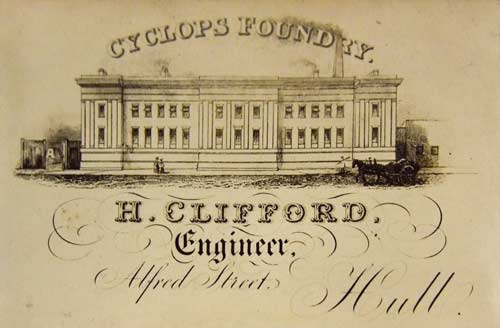

On completion of his apprenticeship with Simpsons he returned to Hull, where in 1844 he entered into partnership with Thomas Brown, trading as the Cyclops Foundry. Soon after a partnership was formed with Edward Gibson Sr. to make iron ships at the Groves Yard. Brown’s financial difficulties led to the dissolution of the partnership in 1849 with substantial losses, and the Cyclops Foundry also closed. [HDC]

Cyclops Foundry business card (c. 1844)

H. Clifford

Engineer

Alfred Street, Hull

Image from Clifford family photograph album,

courtesy of Hull Maritime Museum |

Clifford then considered emigrating but did not pursue this course. In 1851 he applied for the post of Superintending Engineer at the Waterman Steam Packet Company, but despite an impressive array of testimonials he failed win this position.

The 1851 English census shows that Henry, now aged 29, had moved to London, and gives his profession as “Engineer.” He was residing, presumably as a lodger, at 2 Windsor Terrace, Finsbury, the house of Caleb Pizzie and his family. Pizzie was a commission agent and carpet manufacturer with premises nearby. Windsor Terrace was just off City Road, around the corner from St Luke’s Workhouse, so it was perhaps not the best of areas at that time. [2a, b].

“Windsor Terrace, City Road” is the location of Mr Micawber’s house in Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield, published in 1850. Copperfield becomes Micawber’s lodger, and is taken to: “... his house in Windsor Terrace (which I noticed was shabby like himself, but also, like himself, made all the show it could)...”. Micawber is a commission agent for Copperfield’s employer, but soon falls into bankruptcy and goes to debtors’ prison, and Copperfield has to move.

This episode in David Copperfield was taken directly from Dickens’ own childhood experiences in the 1820s. Falling into reduced circumstances, his family lived for a time in a shabby home in Bayham Street, Camden Town, just a couple of miles from Windsor Terrace, and his father was eventually sent to debtors’ prison.

Like Mr Micawber, Henry Clifford’s landlord, Caleb Pizzie, had been declared insolvent (in 1847, when he too was a commission agent), and was perhaps reduced to taking in a lodger to help make ends meet. He was bankrupt again in 1854, when he was in the Debtors Prison for London and Middlesex and his estates and effects were assigned to his creditor.

The area has been re-developed but Windsor Terrace remains, now intersecting Micawber Street at its north end. |

Charles Bright and the 1857/58 Atlantic Cables

Clifford had met Charles Bright before the occasion of Bright’s marriage in the summer of 1853. Bright had known his future wife, Hannah Taylor, for several years before his marriage; she is described in the biography as “Miss Taylor, daughter of John Taylor of Bellevue, Kingston-upon-Hull.” Henry Clifford was born in Hull, and, as noted below, was a cousin of the Taylors.

Charles Bright’s wife is frequently mentioned in the biography, but her first name is not given until the Appendix to volume 2, which quotes Bright’s obituaries from the technical press of the time. The obituary in the 11 May 1888 issue of The Electrical Engineer notes in passing that his wife was the former Hannah Taylor. [4] |

Henry Clifford was introduced to the Atlantic cable project in late 1856 through his connection with Charles Bright, and served as an engineer on all five of the early Atlantic cable expeditions, from 1857 to 1866.

Bright was engineer in charge of the 1857 expedition, and Clifford’s first involvement in the project is described in Bright’s biography [vol 1 p 134]:

When once the wheels had been fairly set in motion, it was necessary for Charles Bright to gather round him a competent staff of engineers, ready for the expedition. First of all, as his chief assistant, he secured the services of Mr. Samuel Canning, who had laid the Gulf of St. Lawrence cable for Messrs. Glass & Elliot, in the preceding year. The next place was filled by Mr. William Henry Woodhouse, who had laid cables for Mr. Brett in the Mediterranean. Then came Mr. F.C. Webb, who had probably been associated—in one capacity or another—with more early cable work than any other single telegraph engineer. Finally, Mr. Henry Clifford joined. He was a cousin of the Taylors, and was in this way introduced to the undertaking, besides being a mechanical engineer of considerable experience. [5]

Clifford’s work was on the paying-out machinery, which would remain his area of expertise through much of his subsequent career. An early book on the preparations for laying the Atlantic cable, published by the Atlantic Telegraph Company in July 1857, notes:

The actual manufacture of the paying-out machinery, arranged by Mr Bright, has been carried on under the superintendence of Mr Henry Clifford, whose experience and talent in mechanical engineering has proved of great service to the Company. [6]

The expedition got under way in August 1857 [vol 1 p 183]

Laying the First Ocean Cable [1857]

Charles Bright, with his chief assistants, Messrs. Canning,

Woodhouse and Clifford, had taken up quarters on board

the Niagara, besides Bright’s brother-in-law, Mr. Robert

John Taylor, who accompanied the expedition as a visitor.

Here were also Mr. Field and Professor Morse.

Mr. Webb was quartered on the Agamemnon, together

with Professor Thomson and Mr. H.A. Moriarty as Navigating

Master. The latter had been specially detailed by

the Admiralty on account of his skill in that class of work.

Mr. C.V. de Sauty, a gentleman of considerable practical

experience, was placed in charge of the electrical arrangements

on board the Niagara, subservient, however, to the

orders of Mr. Whitehouse from shore. Mr. J.C. Laws was

also there. Mr. Whitehouse was not able to go out on the

expedition for reasons of health. [7]

Clifford’s next mention in the biography comes later that year, after the failure of the 1857 expedition [Vol.1 p.200]:

In the middle of October, Bright proceeded to Valentia,

accompanied by Mr. Clifford, in a small paddle-steamer, with

the object of picking up some of the cable near here. After

experiencing a series of gales, over fifty miles of the main

cable were recovered, and the shore end buoyed ready for

splicing on to in the coming year. Whilst engaged in the

above work the subject of our biography penned the following to his wife, which serves to describe the operation

and the apparatus employed :

VALENTIA, October 24th, 1857.

I send you a gift from Henry Clifford, a view from our window at the inn here. The steamer to the right is the Leipsig. The pier is the breakwater of Valentia Harbour. The queer-looking thing to the left is an apparatus I have fitted up for under-running the cable. It is composed of two very large long iron buoys fixed together like a twin ship with a platform of timber over it. On this, at each end, is a saddle with a deep groove for the cable to run in. The cable being on the near shore, it is towed along. When near the end of the heavy cable I shall take it off, cut the cable, buoy the heavy end, and begin winding up the small one as we go on. [8]

This is the first published mention of Clifford’s artistic talent. As a engineer he was would have been skilled in mechanical drawing, but he was also a good artist in watercolours and oils, taking the opportunity of quiet times during cable voyages to make drawings of the ships and the scenery. Some of his drawings were used as the basis for woodcuts in the Illustrated London News in 1858, and a number of his paintings are reproduced in Sir Charles Bright’s biography and in Charles Bright’s 1898 book, Submarine Telegraphs. More information on Clifford’s art appears below.

Clifford was also involved with the preparations for, and sailed on, the two expeditions of 1858.

Saward:

September 1857:

During the progress of the work in 1857 the attention of the Board

had been directed to the mechanical talent and experience of Mr. W. E.

Everett, the chief engineer of the United States’ ship Niagara, and they

now resolved to consult him with reference to the alterations and

improvements required in the future paying-out machinery. They, therefore,

nominated a Committee, consisting of Mr. Penn of Greenwich,

Mr. Field of the firm of Maudslay, Son, and Field, and Mr. Lloyd the

chief of the Steam Department of Her Majesty’s Navy, to act with

Mr. Everett, and at once to proceed to Plymouth to examine the

machinery and mechanical appliances in use by the Company, and to

report thereon to the Board.

Upon this report the Directors determined to act, and as the consent

of the United States’ Government was necessary, prior to Mr. Everett’s

being able to devote his attention to the Company’s service, an application

to the Government at Washington was made by the Directors to

allow Mr. Everett to return to England early in 1858, for the purpose of

superintending and carrying out the manufacture of machinery in the

form suggested by himself and the Committee.

January 1858:

Mr. Everett was ... appointed to prepare, in consultation with Messrs. Lloyd, Penn, and Field, and assisted by Mr. Henry Clifford, an experimental set of paying-out machinery for the purpose of determining upon the changes in construction that might (in consultation with the Scientific Committee) be deemed advisable to remedy the defects of the former apparatus. [9]

Everett spent about three months working at the premises of Easton & Amos, who were manufacturing the paying-out machinery, and in April 1858 invited his colleagues to inspect the work.

Mullaly quotes this letter from Clifford [1858 p 173]:

LONDON, April 23, 1858.

GEORGE SAWARD, ESQ., SEC. of ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH Co.

SIR—I beg to say that I have attended at the works of Messrs. Boston & Amos every day during the construction of the new paying-out machinery, and saw it working on Thursday last. It is, in my opinion, well adapted to the intended purpose, and I have nothing to suggest that could render it more perfect. I am, dear sir, your most obedient,

HENRY CLIFFORD. [10]

Mullaly opens his book with verbal sketches of the dramatis personae of the early Atlantic cable expeditions [1858 p 44]:

MR. CLIFFORD.

Although occupying a comparatively subordinate position, Mr. Clifford is an engineer of great skill and ingenuity, and a draughtsman of more than ordinary ability and acquirements. He was connected with Mr. Everett as an assistant in superintending and forwarding the construction of the present machinery, in which work he rendered material service. The experience which he obtained from his connection with the engineering department of the enterprise during the first expedition was of great advantage to him, as it has proved indeed to all who were then connected with the undertaking. The putting up of the machinery on board the Agamemnon was effected under his direction, and he had partial charge of the laying of the cable from that ship. One of the main features in Mr. Clifford’s character is his good, sound practical common sense, to which he appears to subordinate every thing, and which enables him to see things in their right light. Mr. Clifford is also a native of England. [11]

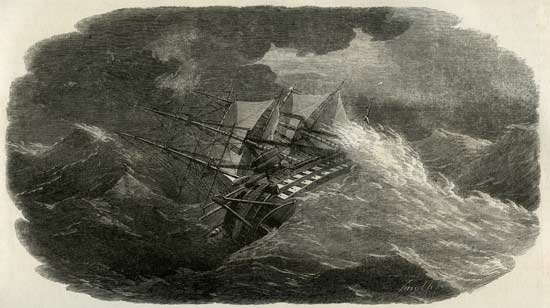

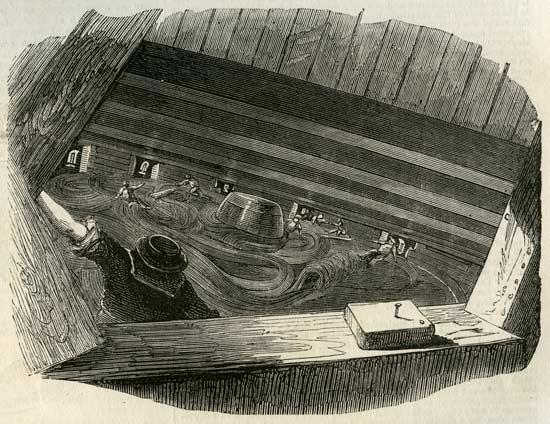

The first expedition of 1858 left Plymouth on 10 June, but a few days into the voyage the fleet ran into a week of gales, during which it was feared that the shifting cable would breach the sides of the Agamemnon. Clifford’s drawings of the ship in the storm were used as the basis for a series of woodcuts published in the Illustrated London News Supplement dated 31 July 1858. The cable fleet survived the storms, but the expedition had to be abandoned after the cable broke on 29 June.

The “Agamemnon” in a Storm

Illustrated London News

It’s interesting to compare the newspaper version of this scene (above), re-drawn from Clifford’s original by the ILN’s woodcut artists, with Clifford’s versions (below), reproduced from Bright [1898] and an original painting still in the Clifford family.

Accounts of the storm in books of the time report that the Agamemnon heeled over to 45 degrees in either direction, which Clifford has accurately reproduced in his paintings; the ILN evidently felt the need to exaggerate this for dramatic effect. |

HMS Agamemnon

21 June 1858

Bright biography, 1898. v.1 p.247

After the painting by Henry Clifford |

HMS Agamemnon

Painting by Henry Clifford

Image courtesy of Jacy Wall

The ILN published two more scenes from the storm based on Clifford’s artwork. Again, the effect of the storm on the ship’s store of coals has been exaggerated from Clifford’s drawing, although it is of course possible that he sent a different sketch to the newspaper. |

Breaking Adrift of the Coal on the “Agamemnon”

Illustrated London News |

Breaking Adrift of the Coal on Board HMS Agamemnon

Painting by Henry Clifford

Atlantic-Cable.com Collection

Reproduced in Bright biography, 1898. v.1 p.250

|

Displacement of the Cable on Board the “Agamemnon”

Illustrated London News

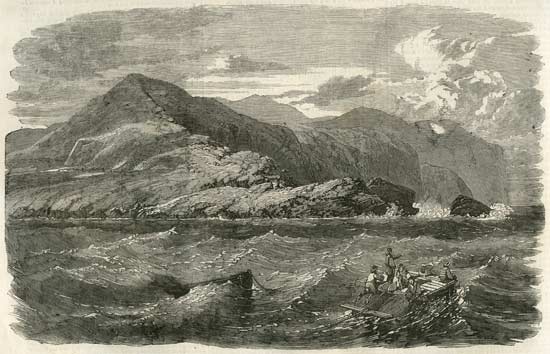

The ILN’s article on the cable expedition included several views of Valentia, which may have also been from drawings by Clifford, who was credited only as follows:

“The engravings of the Agamemnon are from sketches obligingly forwarded by a gentleman who was on board that vessel during the expedition.”

|

Valentia: Catamaran for Under-running the Shore End of the Cable

Above: woodcut from ILN; below: Clifford’s drawing from Bright, 1898 |

|

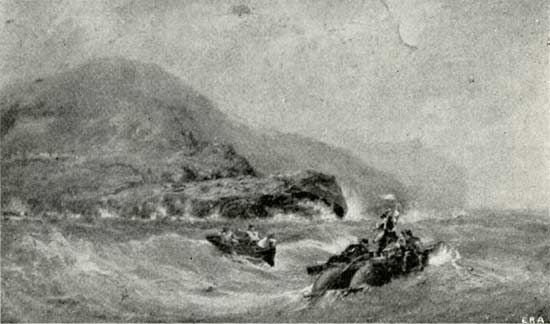

After the return of the ships to Ireland, a second expedition was quickly mounted, setting out on 17 July 1858. Charles Bright was again in charge, with Canning and Clifford assisting him on the Agamemnon. The two ships of the cable fleet made a rendezvous in mid-Atlantic and spliced the sections of the cable that each was carrying. The Niagara then steamed for Newfoundland, and the Agamemnon for Ireland. Nearing the successful conclusion of the voyage, Clifford made a drawing of the Agamemnon as she approached Ireland on 1 August 1858. [12]

H.M.S. Agamemnon Completing the First Atlantic Cable

Reproduced in Bright biography

After the painting by Henry Clifford |

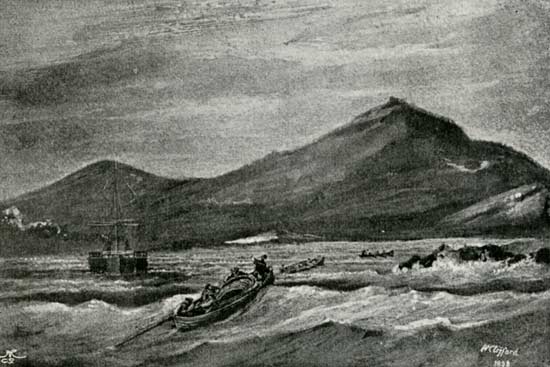

There is also a second drawing by Clifford from this expedition reproduced in Bright’s biography: the Irish shore-end of the cable being landed by small boats. [vol 2 p 319]

In the afternoon of Thursday, August 5th—as already

described in the Times report—Charles Bright and his staff

brought to shore the end of the cable, at White Strand

Bay, near Knight’s Town, Valentia, in the boats of the Valorous, welcomed by the united cheers of the small crowd

assembled. [13]

Landing the Irish Shore End of the Cable

Drawing by Henry Clifford, reproduced in Bright biography. |

Because of unforeseen technical problems, although the cable had been successfully landed and messages were sent in both directions over a period of several weeks, transmissions through the cable failed on 20 October 1858.

Glass Elliot - Mediterranean Cables

After the failure of the 1858 cable Clifford joined Glass Elliot & Company, one of the earliest cable manufacturers.

One of his first projects for the company was the Cromer-Emden cable, made for the Submarine Telegraph Company. The cable was completed on 4 November 1858 by CS William Cory, with Clifford and Canning as engineers.

[Mechanics’ Magazine, 12 November 1858, p.467]

In January 1859 Canning and Clifford were awarded a provisional UK patent for “Improvements in machinery for paying-out and for recovering or picking up submarine telegraph ropes, cables, or chains.”

In June of that year Henry Clifford married Elizabeth “Bessie” Alexander at Yeovil, Somerset. [3 - Clifford family album photo caption & BMD records]

In late August 1859 Henry noted in a letter to his mother: "I wrote you a few lines yesterday stating that I expected to go to Malta and Sicily with the cable. It is now decided that I do go, and I have no alternative but to take the duty with a good grace, though it is no little disappointment. "

An unsigned watercolour [PAG9922] in the Henry Clifford collection of the National Maritime Museum is captioned: “Maritimo E.N.E. 10 miles off September 26th 1859”. Now known as Marettimo, this is the westernmost of three small islands off the coast of Sicily between Trapani and Marsala.

Henry presumably painted this watercolour on the Malta/Sicily cable voyage described in the letter to his mother. This cable was laid for the Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Co using CS Lady Seale.

A further provisional patent was issued to Clifford in 1861 for “Improvements in apparatus to be employed in coiling and paying-out electric telegraph cables.”

By the time of the census of 1861, taken on 7 April, Henry Clifford had evidently become quite prosperous. He was living at 19 Park Row, Greenwich, with his wife Elizabeth, a one-year-old son, William Alexander Clifford, and two servants: a nurse and a cook. [14]

Also present in the Cliffords’ house on census day in 1861 were Thomas Alexander and Mary W. Alexander. Thomas’s occupation, at age 21, was shown on the census as “Assistant Telegraph Engineer”; it is likely that Henry secured a position for his brother-in-law through his connections in the cable industry. Thomas Alexander worked for Charles Bright’s company for a number of years. |

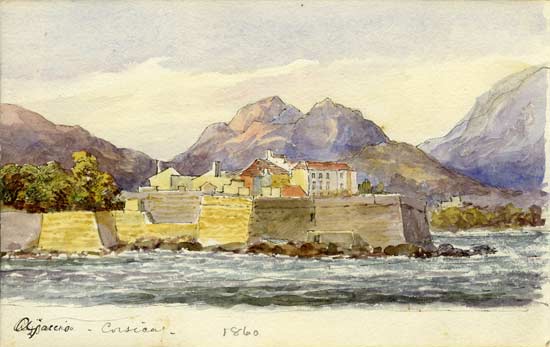

In June 1861 Henry was engineer on the Malta and Alexandria cable expedition, again assisting Samuel Canning, and sailed on the Malacca. Wildman Whitehouse was also on this expedition. On this voyage the Malta-Tripoli section was laid, and Henry arrived at Malta on 6 June. From there he went to Toulon to lay the Corsican cable, where he painted this watercolour:

Ajaccio - Corsica

This watercolour is mounted in one of Alexander Clifford’s albums

Although dated "1860" in pencil, this was added later

and the painting is almost certainly from 1861.

Image courtesy of Jim Kreuzer |

Later that year, in September 1861, Clifford continued the cable from Alexandria to Benghazi [Bright 1898 p64]. For more information see this page. His second son, Henry Charles, was born on 10 September while Clifford was away laying the cable.

While on this expedition he painted two watercolours of Libyan coastal scenery between Ras al Milhr and Benghazi. Both were made on 21 September 1861, one at 3pm “139.1 Nauts from Ras al Milhr”, and one at 4pm “145 Nauts”, according to the pencil captions on the back of each painting.

Marked in pencil on the mount:

Sketch made on board the Rangoon

laying

cable between Malta & Alexandria.

3.75 x 10.25 inches; signed: H. Clifford

Caption in pencil on back of watercolour:

Wad Halaw

3 P.M. Saturday Sept. 21st 1861.

44460 = 139.1 Nauts from Ras al Milhr

Atlantic-Cable.com Collection |

Marked in pencil on the mount: Marabut, 4 P.M. Sep 21 1861

3.75 x 10.25 inches; signed: H. Clifford

Caption in pencil on back of watercolour:

Marabut

4 P.M. Sep. 21.

46400 = 145 Nauts

Atlantic-Cable.com Collection

Clifford signature on Marabut watercolour |

|

Following the line of the cable from Ras al Milhr (near present-day Bardiya) for 139.1 nautical miles (~258 kilometers) gives a location for the paintings somewhere near Derna, on the Libyan coast. About the same distance again would have brought the expedition to Benghazi.

The Rangoon arrived at Benghazi on 23 September 1861, two days after the date of the watercolours, and from there returned to England. The Malacca completed the final section, from Tripoli to Benghazi, between 26 and 28 September, and communication between Malta and Alexandria was then established.

In late July 1862 Canning and Clifford were engineers for the laying of the Lowestoft to Zandvoort (Holland) cable by CS Hawthorns. The cable was made and laid by Glass, Elliot for the Electric and International Telegraph Company.

[Mechanics’ Magazine, 1 August 1862, p71]

In January 1863 the Sardinia to Sicily cable expedition used Canning and Clifford’s paying-out machinery on CS Hawthorns. Samuel Canning was engineer on this voyage; it’s not known if Clifford was also on board. In September of that year a second Malta to Alexandria cable was laid, with Clifford as engineer on CS Hawthorns. [The Times] [16]

1865 Atlantic Cable

In 1864 Glass, Elliot merged with the Gutta Percha Company to form the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company Ltd. (Telcon). This merger formed a company whose main purpose was to make an attempt to lay the Atlantic cable in 1865 using the Great Eastern.

The Great Eastern, under Captain Birch, sailed in July of 1864 from Liverpool to Sheerness, where she was to take on the cable for the 1865 expedition, then in course of being made by Telcon. Daniel Gooch, Samuel Canning and Henry Clifford were on board “with a view of watching the working of the machinery” [The Telegraphic Journal, 16 July 1864 p. 35].

By December 1864 the ship was almost ready to load cable, the delivery of which was expected to begin in January 1865 [The Telegraphic Journal, 17 December 1864 p. 292].

The expedition set sail on 15 July 1865.

1869 Henry Field

The engineering department was under charge of Mr. Samuel Canning, who, as the representative of

the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, was chief in command in all matters relating to laying the cable. For this responsible position no better man could have been chosen. Before the voyage was ended, he had ample opportunity to show his resources. He was ably seconded by Mr. Henry Clifford. Both these gentlemen had been on board the Agamemnon in the two Expeditions of 1838. They had since had large experience in laying submarine cables in the Mediterranean and other seas. It was chiefly by their united skill that the paying-out machinery had been brought to such perfection, that throughout the voyage it worked without a single hitch or jar. They had an invaluable helper in Mr. Temple. [17]

1865 Bright

On behalf of the contractors, the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance

Company, Mr (now Sir Samuel) Canning was the engineer in charge

of the expedition, with Mr Henry Clifford as his chief assistant. Both these gentlemen had been engaged with Sir Charles Bright on the first Atlantic expedition, and had had much experience alike in cable work and mechanical engineering. [18]

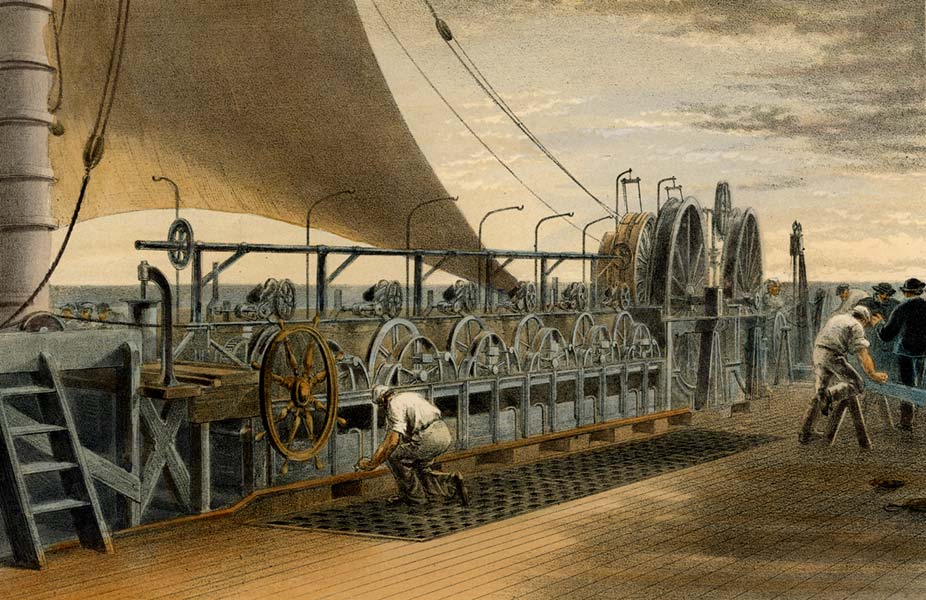

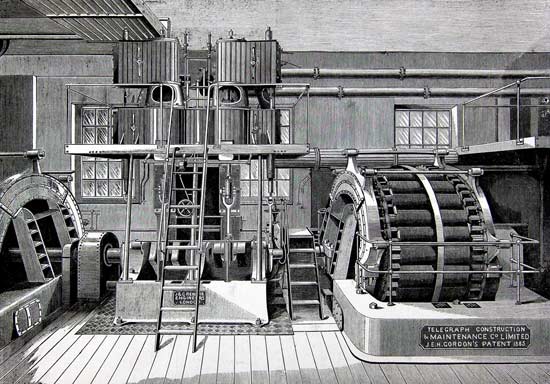

Clifford was largely responsible for the design of the paying-out machinery for the Great Eastern, which was being converted from a passenger ship for the cable expedition. This drawing of Clifford’s machinery by Robert Dudley, the official artist for the 1865 expedition, was published in William Russell’s book about the voyage. [19]

Robert Dudley: The paying out machinery in the stern of the Great Eastern

Designed by Henry Clifford, the paying-out machinery used on the Great Eastern incorporated an automatic release mechanism and jockey wheels. The machinery had been designed to keep the cable taut as it paid out over the Great Eastern’s stern.

|

Extracts from Narrative Of The Atlantic Telegraph Expedition, 1865

by John C. Deane

Samuel Canning, chief engineer of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company (Telcon) was in charge of the laying with Mr. Clifford supervising the machinery. They were assisted by Messrs Temple and London plus eight engineers and mechanics. The cable laying staff was provided by Telcon.

This beautiful and ingenious machinery has been invented by Messrs. Canning and Clifford, and has worked up to this time with admirable regularity and precision. At noon yesterday, 531.57 nautical miles had been paid out, between 1,529 to 1,950 fathoms. Distance from Valentia 476 miles. We asked the Terrible to prevent any ships from crossing the cable astern, and she replied, “Yes, if possible."

But there is Mr. Canning hurrying along to the bow of the ship: he has never for a moment lost his self-possession. He soon returns midships and is accompanied by Mr. Clifford, his able assistant, and a staff of workmen.

Practical conclusions unanimously arrived at by those engaged in various capacities in the expedition.

"1st. That the steam-ship Great Eastern, from her size and consequent steadiness, together with the better control obtained over her by having both the paddles and screw, render it possible and safe to lay an Atlantic Telegraph, in any weather.

"2d. That the paying-out machinery, constructed for the purpose by Messrs. Canning and Clifford, worked perfectly, and can be confidently relied on. [20]

The 1865 expedition ended in failure when the cable broke and the end could not be recovered after many days of grappling.

| |

Sketch by Henry O’Neil

for the newsletter he

published on the Great Eastern in 1865 |

Irish artist Henry O’Neil, who was on both the 1865 and 1866 expeditions, gives a good account of Clifford’s work on the 1865 voyage. He was also responsible for sketches of Clifford and other cable noteworthies on this expedition. [21]

Much had been learned on the 1865 expedition about working with cable in deep water, and it was obvious from the many successes of the voyage that completing the laying of an Atlantic cable was within reach.

With every expectation of a successful outcome, another expedition was mounted in 1866 using the Great Eastern with substantially the same crew, but with some modifications to the equipment based on the experiences of the previous year.

1866 Atlantic Cable

1866 Bright/Story

The previous paying-out machinery on board the Great Eastern was altered to some extent by Messrs. Penn to the instructions of Messrs. Canning & Clifford. Though different in detail, the main improvement over the 1865 gear consisted in the fact that a 70-horse-power steam-engine was fitted to drive the two large drums in such a way that the paying-out machinery, as in 1858, could be used to pick up cable during the laying, if necessary, thereby avoiding the risk incurred by changing the cable from the stern to the bows. This addition of Penn trunk-engines, as well as the general strengthening of the entire machinery, was made in accordance with the designs of Mr. Henry Clifford.

The principal members of the staff acting on

behalf of the contractors in this expedition were

the same as in that of the previous year. Mr.

Canning was again in charge, with Mr. Clifford

and Mr. Temple as his chief assistants. [22]

The 1866 expedition was a complete success; the laying of the new cable was uneventful, and the ship then set out to recover the lost cable of the year before.

Extracts from Recovery of the Lost Cable—1866 by Henry Field.

“I made my way with others, in accordance with an invitation from Willoughby Smith, to the electricians’ room. Here, after another hour’s preparation, during which time the cable had been carefully passed round the drums of the picking-up machinery, and a sufficient length drawn in on board, the severed end was received. And now, in their mysterious, darkened haunt, the wizards are ready to work their spells upon the tamed lightning. Not ‘unholy spells’ are these, or secret; for, though the wizards’ den is but of limited dimensions, they have not been averse to the presence of a few visitors. Mr. Gooch is looking on; Professor Thomson, be sure, is here, a worthy ‘Wizard of the North;’ Cyrus W. Field could no more be absent than the cable itself; I think, too, Canning, hard at work as he is forward in the ship, must have dropped in just for a moment; Clifford, Laws, Captain Hamilton, Deane, Dudley—all have, in their several ways, a great interest in every movement of Willoughby Smith and his brother (and able assistant) Oliver; and, when the core of the cable is stripped and the heart itself—the conducting wire—fixed in the instrument, and these two electricians bend over the galvanometer in patient watching for some message from that far-off land of home to which the great news has just been signalled, then the accustomed stillness of the test-room is deepened; the ticking of the chronometer becomes monotonous. Nearly a quarter of an hour has passed, and still no sign! Suddenly Willoughby Smith’s hat is off, and the British hurrah bursts from his lips, echoed by all on board with a volley of cheers, evidently none the worse for having been ‘bottled up’ during the last three hours. Along the deck outside, over the ship, throughout the ship, the pent-up enthusiasm overflowed; and even before the test-room was cleared, the roaring bravos of our guns drowned the huzzas of the crew, and the whiz of rockets was heard rushing high into the clear morning sky to greet our consort-ships with the glad intelligence.”

The scene at Heart’s Content, when the telegraphic fleet appeared the second time, was one that beggars description. Its arrival was not unexpected, for the success on Sunday morning, that had been telegraphed to Ireland, was at once flashed across the Atlantic, and the people were watching for its coming. As the ships came up the harbor it was covered with boats, and all were wild with excitement; and when the big shore-end was got out of the Medway, and dragged to land, the sailors hugged it and almost kissed it in their extravagance of joy; and no sooner was it safely landed than they seized Mr. Canning, Mr. Clifford, and Mr. Field in their arms, and raised them over their heads, while the crowd cheered with tumultuous enthusiasm. [23]

Great Eastern Paintings

One of Henry Clifford’s favourite subjects was the Great Eastern. He painted many views of the ship engaged in the Atlantic cable expeditions, including a number of variations of the same scene.

|

Great Eastern, probably 1866

Atlantic-Cable.com Collection

Grisaille.

Signed H. Clifford.

7¼ x 10½ inches (184 x 267mm). |

It’s likely that Henry Clifford made sketches or preliminaries similar to the one above while on board ship, then painted the finished oils when he returned to England. The National Maritime Museum at Greenwich has four oil paintings of the Great Eastern by Clifford, as well as several watercolours.

Clifford was at a celebration at Liverpool on board the Great Eastern on 20 September 1866, and attended the Lord Mayor’s banquet given for the members of the telegraph expedition and other notables at the Mansion House in London on 31 October that year. [The Times]

In 1867 the 1866 Atlantic cable had to be repaired, having broken just off the coast of Newfoundland.

The Year-book of Facts in Science and Art by John Timbs

The events connected with the extension of telegraphic communication in 1866 were the most memorable ever recorded in its history; for in that year not only was a complete cable, uniting the Old World and the New, successfully submerged, but another, which was considered irretrievably lost by the general public, was recovered from the depths of the Atlantic. Some of the facts connected with its history and progress during he year 1867 are peculiar and interesting.

The first prominent occurrence was the repairing of the Atlantic cable of 1866, which had been broken some two miles from the Bay of Heart’s Content. It appears that when the shore end of the cable referred to was being laid the Great Eastern, from which it was paid out, was in a fog, and it was laid in a shallower part of the ocean than was originally intended by the engineers. It was found that an iceberg, which had grounded in 27 fathoms, was the cause of the accident, and the cable was repaired in the marvellously short space of 48 hours, under the supervision of Mr. Henry Clifford, C.B.

The same rope broke again in July, about 87 miles from Newfoundland. Thirteen miles of it were picked up by the ship Chiltern, under the direction of Sir Samuel Canning, and laid in a deeper channel than that in which it had formerly been deposited. This was the first case of what may be called ordinary repair to the Atlantic lines, as contradistinguished from picking up and splicing, and the promptitude with which it was effected afforded another proof of Sir Samuel Canning’s ability and skill.

Subsequent Cable Work

A problem encountered with submarine cables in some parts of the world was the attack by so-called Teredo worms (marine borers) on the gutta percha, leading to loss of insulation and failure of the cable. A number of solutions were devised over the years. In 1868 Clifford was awarded a patent for:

“Improvements in the manufacture of submarine telegraph cables.” The core of submarine cables is covered with powdered silica to preserve it from insects. The silica is

preferably made to adhere to yarn previously steeped in pitch or other material, which is afterwards wound

upon the core.

Others in the industry proposed similar solutions, but Bright [1898] notes that “it is believed that none of these ideas have ever been put into practice on anything like an extensive scale.” See below for Clifford’s work on the metal tape which was used from 1879 forward as the standard protection against borers.

The success of the 1866 Atlantic cable expedition was the beginning of a period of rapid expansion of the long-distance cable network. In 1869 Samuel Canning and Henry Clifford were again engineers on Great Eastern for the French Atlantic Cable expedition. [The Times, 4 Feb 1869]

The 1871 census has only a passing mention of Henry Clifford and his family, which then included his wife Elizabeth, their sons William Alexander (born 1860) and Henry Charles (born 1862), and daughter Alice de Clifford Clifford, whose birth was recorded at Greenwich in the first quarter of 1871. The only family member found in the census is William, who was listed as a pupil at a school in Great Baddow, Chelmsford, Essex, about forty miles from London, where he was presumably a boarder. It’s possible that the rest of the family was abroad at the time of the census, which was taken on 2 April 1871.

In 1872 and again in 1873, Clifford was among the guests at Cyrus Field’s celebratory banquets in London.

In October 1875 W.C. Johnson and S.E. Phillips founded the firm of Johnson & Phillips, Charlton, London, specialising in “Complete equipments of cable machinery, accessories and stores for cable laying and repairing steamers.” One of the founding partners, Walter Claude Johnson, had learned the business under Henry Clifford at Telcon; he started work there in 1869 at about age 23, and soon advanced:

When about seventeen years of age Mr. Johnson became an articled pupil to Mr. W.F. Gooch, at the Vulcan Foundry in Lancashire, where he remained for five years. Failing, however, to find work that was congenial to his tastes, and after declining with considerable hesitation the offer of an appointment in a drawing office at the rate of £50 per annum, he resolved to join the applied sciences department, King’s College, London, for a year, and on the completion of this term he was engaged as a draughtsman by Mr. H. Clifford, the engineer of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company’s works.

It was here, in working out designs for improved cable machinery, under the immediate supervision of Mr. Clifford, that he obtained a clear insight into the most advanced form and construction of this important branch of engineering, and his keen observation had ample scope, not only in the direction to which his abilities so conspicuously tend, viz., in the design and construction of machinery, but also in the laying of all the original cables of the Eastern and Eastern Extension Telegraph systems.

He was appointed chief engineer in the laying of the British Australasian cable [1871], the expedition being commanded by Captain Halpin. He left the works of the Telegraph Construction Company to join Mr. S.E. Phillips in establishing a business of their own.

Johnson’s family diary records that even after he went into partnership with Phillips in October 1875 he continued to work at Telcon, and notes that in October 1876, a year later, he was “sacked,” presumably by Henry Clifford. [History of Johnsonn & Phillips]

In 1878 Clifford again addressed the Teredo problem, for which his 1868 patent had described one solution.

Bright 1898 p 381 ff.

According to Mr Clifford’s plan, the metal tape is applied outside the

core instead of outside the serving. It is this which is now in extensive

use in the present day. Clifford’s brass taping was first applied by the

Telegraph Construction Company to a part of the Eastern Extension

Company’s Penang-Malacca cable laid in 1879. Since then it has been

adopted for at any rate all the shallow-water sections of the Eastern,

Eastern Extension, and Eastern and South African cables which are laid

in at all tropical waters, where the teredo et hoc genus omne are liable to

flourish, and where gutta-percha is the insulating medium.

Charles Bright’s comprehensive article on marine borers and Clifford’s contributions to protecting against them may be read here.

Mr and Mrs Clifford.

Image courtesy of Jacy Wall |

Domestic Life

Henry Clifford appears to have moved house twice between the 1861 and 1881 censuses. The 1881 census records two of his children having been born at Greenwich, in 1861 and 1871, and two at Blackheath in 1876 and 1877, but when the 1881 census was taken, on 3 April of that year, the family was living at 1 Lansdowne Place, Lewisham. Both Lewisham and Blackheath are a short distance from the Telcon works on the River Thames at Greenwich.

Clifford’s son William died of accidental gas poisoning in an incident at school in September 1873 when he was 14 years of age [The Times 26 Sep 1873].

The 1881 census shows:

| |

Name |

Age |

Rank, Profession, or Occupation |

Where Born |

| Henry Clifford |

59 |

Telegraph Engineer (Appar Mkr) |

Hull |

| Elizabeth Clifford |

44 |

|

Glastonbury |

| Henry C[harles] Clifford |

19 |

Scholar |

Greenwich |

| Alice De C[lifford] Clifford |

10 |

|

Greenwich |

| Alexander Clifford |

5 |

|

Blackheath |

| Elsie H.B. Clifford |

4 |

|

Blackheath |

Missing on this census is their son Harold Mills Clifford, born at Greenwich on February 9th 1867; perhaps at age 14 he was away at school.

By now even more prosperous, Henry and Elizabeth had five servants: a governess, cook, housemaid, nurse, and parlourmaid.

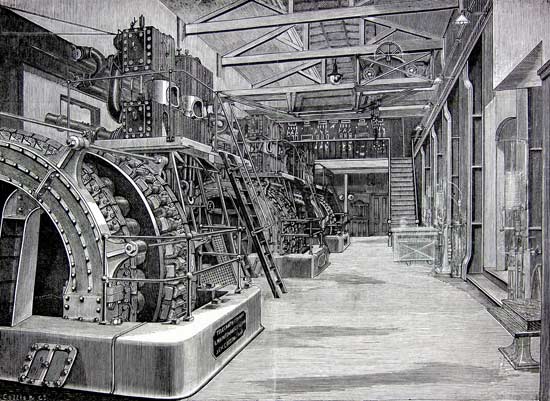

In May 1886 Henry Clifford attended a demonstration of electric lighting at Paddington Station in London, powered by direct current from a central station. The installation was undertaken by Telcon, which by then evidently had an electric light department, to test the practicability of central station lighting. [The Times, 18 May 1886]

Dynamo room, Paddington installation,

showing the three large Gordon dynamos

[The Electrician, 28 May 1886] |

Dynamo room, Paddington installation

Front view of Gordon dynamo and engine

[The Electrician, 28 May 1886] |

In 1888 Clifford was one of the mourners at the funeral of his old friend Sir Charles Bright, on May 7th of that year.

Photograph dated 1890, showing Henry Clifford and colleagues at the Greenwich works of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company.

| R. Dunning |

Father |

Corder |

Bobbie London |

Harry Davis |

Henry Clifford is identified as “Father”, which suggests that the photograph

may

have been either taken or captioned by his eldest son Henry Charles.

|

By the 1891 census, taken on April 5th, Henry, aged 69 and listed as “Submarine Telegraph Engineer”, was a widower, still living at Lewisham. His children Henry Charles, now 29 and an “Artist, Painter, Sculp”; Alice, 20; and Alexander, 15 were at the same address. Elsie, who would have been 14, is not listed. He had three servants, a parlourmaid, cook, and housemaid.

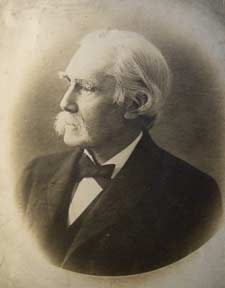

Undated photograph of

Henry Clifford in later life.

Image courtesy of Jacy Wall |

Retirement

On 15 May 1893, at age 71, Henry Clifford retired from his post as Chief Engineer at the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, but he did not lose his interest in the cable industry, retaining the title of Consulting Engineer [letter to Clifford dated 11 May 1893 from Telcon, NMM]. Bright [1898 p 156] notes that Clifford had worked at Telcon for over thirty years, succeeding Sir Samuel Canning as engineer-in-chief. On Clifford’s retirement the post was filled by Francis R. Lucas, who had also worked for the company for many years.

Clifford’s son Alexander also worked at Telcon, from April 1893 until his retirement on 31 December 1927. [Telcon House Magazine No. 7, 1950]

In 1896 it was proposed to celebrate the upcoming jubilee of submarine telegraphy (in 1901) by a Memorial. The names of John Pender, James Anderson, and Cyrus Field were put forward as those to be honoured. This provoked a series of letters to The Times regarding the merits of these commercial men versus those of the scientists and engineers who made the cables work.

This letter to The Times from Henry Clifford lays out the facts from his own experience of the Atlantic Cable expeditions:

Monday October 12, 1896.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES.

Sir,—Lord Selborne’s address to the committee would lead any one to suppose that Sir James Anderson had laid the second Atlantic cable. This is an error. Sir Samuel Canning was the engineer in charge of the expedition; and upon him alone rested the responsibility of the undertaking.

In point of fact the main feature of this expedition was the recovery of the 1865 cable. The possibility of laying a cable in deep water had been previously demonstrated by the late Sir Charles Tilston Bright in connexion with the first Atlantic line; but it remained for Sir S. Canning to prove that a cable could be picked up in the Atlantic, and to him alone all honour for this is due.

A special application was made to the Admiralty for a navigator both as regards the first and second Atlantic cable expeditions; and in each instance Staff-Commander Moriarty, R.N., C.B., was deputed for the purpose, much to the credit of that Department.

Sir James Anderson was the captain of the Great Eastern, but in no way responsible for the cable operations.

With reference to the first Atlantic cable, Mr. Cyrus Field came over to England to raise the necessary capital; and, undoubtedly, much credit is due to him for his indomitable energy and perseverance.

Sir John Pender acted in a similar capacity in the further extension of submarine telegraphs.

But certainly all the three names pressed forward in the proposed memorial are those of commercial men rather than of engineering pioneers in this great engineering work.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

HENRY CLIFFORD, Assistant Engineer to Sir C.

Bright, First Atlantic Cable; Assistant Engineer

to Sir S. Canning, Second Atlantic Cable.

It was later decided by the Committee in charge of the proposal to limit it to a memorial for Sir John Pender.

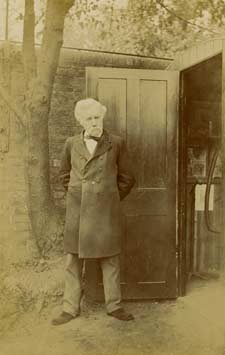

Dated 1898 in pencil on the reverse, this CDV perhaps shows Henry Clifford in the back yard of his Lewisham home. |

The 1901 census shows Henry still at the same address in Lewisham, aged 79 and now “Telegraph Engineer. Elect App. Retired”. His daughter Alice, now 30, is still at home, and there are three servants, a cook, parlourmaid, and housemaid. His son Henry Charles is now married and living in Hammersmith, occupation “Artist Sculp”, at which he had become quite successful. Harold was married and living in Kensington with his wife and daughter; his sister Elsie was also with them.

Henry Clifford died 18 May 1905 at his residence, 1 Lansdowne Place, Blackheath, Kent, at age 83. A letter of condolence from the Royal Photographic Society notes that he was “long a member of this Society”. [letter to Clifford’s son dated 23 May 1905, NMM]

The final entry in official documents is the probate of his will on 1 July 1905 to Henry Charles Clifford artist, William Parker Burkinshaw chartered accountant, and John William Alton Batchelor solicitor. Effects £89,210 9s. 4d. [equivalent to about £5m in 2010]

|