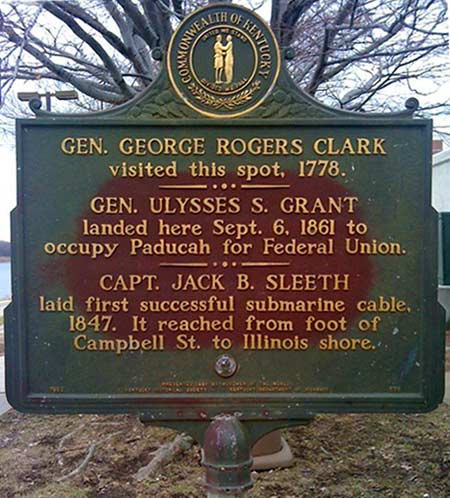

In May 2012, one of my correspondents from England was visiting Paducah, Kentucky, where he found this historical marker on the banks of the Ohio River:

Capt. Jack B. Sleeth

laid first successful submarine cable,

1847. It reached from foot of

Campbell St. to Illinois shore.

Presented 1963 by Woodmen of the World

Marker #575 |

I was not familiar with Captain Sleeth or his cable, so I consulted some historical references.

Samuel Morse had experimented with a cable between the Battery and Governor’s Island in New York Harbor in 1842, and in 1845 Charles West of S.W. Silver & Company in London manufactured one mile of cable insulated with rubber and carried out tests on it in Portsmouth Harbour. In 1850 a cable was laid under the English Channel from Dover to Calais, and the first cable to successfully carry commercial traffic was laid on the same route a year later.

Captain Sleeth’s cable, as described on the marker, would have run under the Ohio River from Paducah to Illinois, and if it had indeed been laid in 1847 it would have been the earliest underwater cable to be placed in commercial service.

Sleeth, a riverboat captain, is known to have been involved with the St Louis and New-Orleans Telegraph Company in Paducah after its establishment in 1849 [Act of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, 19 February 1849], and the river there was crossed with a line strung from tall masts in 1850 [Tal Shaffner’s “Telegraph Manual”, 1859]. Newspaper stories of the period report that Tal Shaffner, assisted by Sleeth, laid a gutta-percha insulated cable under the river in 1853; none of these mention any earlier attempts by Sleeth.

The marker was presented in 1963 by Woodmen of the World Life Insurance Company on the occasion of its Kentucky state convention being held in Paducah from 24-26 March that year. A preview of the convention events was published by The Sebree Banner in its issue of 22 March 1963; this extract mentions the marker:

At 1:30 p.m. March 25 the convention will move to the waterfront between Broadway and Kentucky Avenue for the presentation of a historical marker to the City of Paducah. It will mark the spot on the waterfront at Paducah where George Rogers Clark lived and which he used as a base of operations for his expedition into the Middlewest. Also on the marker will be a notation commemorating the spot where the first submarine cable was placed across a navigable stream during warfare.

The reference to the first submarine cable being laid “during warfare” is somewhat of a puzzle, although another entry on the plaque (not mentioned in the newspaper report) was the landing at Paducah of General Ulyssess S. Grant during the Civil War, so perhaps these two events were conflated.

The Woodmen of the World was (and is) a fraternal benefit society, with a long history of community service by its local chapters, which on this occasion included the presentation of the historical marker to the City of Paducah. The wording of the marker was the subject of discussion among the Woodmen, the Paducah Chamber of Commerce, historian and newspaper columnist Hall Allen, and the chairman of the Kentucky Historical Highway Marker Program, W.A. Wentworth.

The archive of the Kentucky Historical Society, the state agency which now manages historical markers, has documents from this 1963 process which show that the date of 1847 for Sleeth’s cable could not be substantiated at the time, and that its use on the marker was almost certainly arbitrary. See Appendix B at the end of this page for full details; this includes evidence that an earlier marker at the foot of Campbell Street (dating to no later than 1920) bore a date of 1857!

In 2013, when the original research for this page was under way, The William Clark Market House Museum, Paducah’s local history museum, had a note on its Frequently Asked Questions page that “John B. Sleeth, who invented the first underwater submarine cable” was a resident of Paducah, but this has since been removed from the site [archive copy here].

The first mentions I can find of a cable being laid in the 1840s come from 1895, in the form of anecdotal descriptions in letters from newspaper readers responding to the obituary of Sleeth as published in Washington and New York papers (and no doubt others elsewhere). Sleeth’s obituary and the responses to it are reproduced below.

None of the dates given for Sleeth’s cable in these later accounts match the historical record; one report says that Sleeth was associated with Shaffner in 1845 and laid his cable about a year later, while the historical marker has it as 1847. But the telegraph line at Paducah was not established until 1849.

The documented facts of the Paducah river crossing are as follows:

This story from the Charleston Courier [Charleston, South Carolina, 22 August 1853], credited to the Paducah Pennant, was reproduced in whole or in part in several other newspapers across the country (including Scientific American in its issue of 27 August 1853):

Submarine Telegraph under the Ohio.

The Submarine Telegraph Cable on the St. Louis and New-Orleans Telegraph line was laid across the Ohio river, at Paducah Kentucky, on Monday, the 26th ult. [26 July 1853]. The Paducah Pennant gives the following account of it:

We examined this strange piece of mechanism a few days previous to this time it was deposited in its watery abode, and were not a little astonished at its great strength. It recomposed of a large iron wire covered with three coatings of gutta percha, making a cord of about five-eighths of an inch in diameter.

To protect this from wear and for security of insulation there are three coverings of strong Osnaburg, saturated with an elastic composition of non-electrics; and around this are eighteen large iron wires, drawn tight as the wire will near, and the whole it then spirally lashed together with another large wire passing around at every three-quarters of an inch. The whole forms a cable of near two inches in diameter, and It is much the largest and most substantial cable of the sort in the world.

We are told that the great cable across the channel from England to France is inferior in size to this, and by no means as well insulated for electrical application; while in point of strength it will not compare at all with the one at this place. The British wire across the channel is surrounded by eight wires only, while ours has eighteen. Ours is spirally lashed, while the British is not. The electric wire in the British cable has but one coating of gutta percha, while ours has three.

This stupendous wire, which now conducts the lightning from shore to shore, beneath the bed of the majestic Ohio, is 4,200 feet in length, and the longest one to be found in the United States. It has been constructed by that amiable and accomplished gentleman, Tal. Shaffner, Esq. late President of the company, and now Secretary of the American Telegraph Confederation, assisted by J.B. Sleeth, mechanical engineer. These gentlemen have made improvements in the construction of cables, both scientific and mechanical, which will entitle them to letters patent, and the country may well be proud of them, as men of skill and ability in whatever they may undertake.

The wires on this line, we understand, have been exceedingly troublesome and expensive to the Company; upwards of $20,000 having been expended in unsuccessful efforts to cross the Ohio River in such a manner as to secure them against accident; but this great effort has accomplished the object, and there can be no future loss sustained, on account of breakage of masts, wires, &c

We rejoice that the work has been successfully accomplished, and that it has proved fully equal to the most sanguine calculation our friend Shaffner had made of its utility. We had the pleasure of receiving the first dispatch which ever passed under the Ohio, on this mammoth cable, which run as follows:—

“Illinois Bottom, July 26, 1853.

“Col. Pike :—I send this through the great cable, successfully laid to-day.

“Shaffner.”

The Paducah Journal, quoted in Tal Shaffner’s Telegraph Companion (Vol. I No. 1, January 1854) had this version of the events:

Shaffner’s Lightning Ferry.—On Monday, the 26th July, Tal. P. Shaffner, Esq., whose pet is lightning, laid across the Ohio River, on the New-Orleans and St Louis Line, about a mile below town, his great telegraph cable, the longest in America, and the largest in the world. This cable is 4¼ inches in circumference, fourteen hundred and forty yards long, and weighs eleven thousand pounds.

Last fall Mr. Shaffner constructed and laid across the Tennessee River his first cable of this kind. During the winter and spring the freshets were greater than usual, and the great cable triumphantly resisted all forces coming in contact. The experiment confirmed the most sanguine hopes of the constructor, and Mr. Shaffner has commenced laying the cables at every crossing on the line. This line has more submarine telegraphing than any other line in the United States. Heretofore the companies have been much annoyed by the inefficacy of their submarine apparatus. Mr. Shaffner has been assisted in the construction of this cable by J.B. Sleeth, mechanical engineer.

The cable between England and France is inferior to this in strength and non-electric incasements.

It would not surprise us if Col. Shaffner should, before long, mount his pet and pass over to Europe, to offer his improvements to the trans-Atlantics. His energetic efforts and improvements in rendering subservient to man the fierce element, merit not only the admiration of the world, but a most fruitful reward.

These accounts give the date of the Paducah cable as 26 July 1853 and credit it to Shaffner, assisted by Sleeth. The Paducah Journal article also notes that Shaffner had laid his first river cable the previous year.

So where did the 1847 date on the historical marker come from? As with other stories about early submarine cables, this one appears to have been re-told many times over the years - with changes along the way. Writing over forty years after the event, on the occasion of Sleeth’s death in 1895, it would not have been easy to go back to original sources, and all the later reports appear to be based on hearsay. It seems likely that as Sleeth and his family told the story some of the dates and details changed, and this continued even after Sleeth’s death.

When John B. (Jack) Sleeth died in 1895, obituaries were published in a number of newspapers. The Evening Star [Washington DC)] in its issue of 13 March 1895 had this story:

Originator of Submarine Telegraph

St. Louis, Mo., March 18. A special from Paducah, Ky., says: Capt. Jack Sleeth, the veteran steamboat man, famous in river circles, died at his home here of cancer.

…

In 1845 he erected the first telegraph in this section, from St. Louis to Nashville, and conceived the idea of burying the wire under the Ohio river at this point. Cyrus W. Field is said to have borrowed his idea of the Atlantic cable from this invention.

A letter in the [New York] Sun expanded on this:

Letters From The People

Capt. Jack Sleeth Said to Have Laid the First Submarine Cable

Mr. R.D. Warfield writes to THE SUN as follows from Louisville, Ky:

The death of Capt. Jack Sleeth, at Paducah, Ky., last week, has recalled a circumstance which is probably not generally known, and which connects him in an important manner with the pioneer movements which resulted in the construction of the great magnetic cables of the world.

Capt. Sleeth laid the first submarine cable. It crossed the Ohio river from Paducah, Ky., to Brooklyn, Ill. and formed a part of the telegraph line from Nashville, Tenn. to St. Louis, Mo. It was a crude affair, the wire being wrapped in sacking and afterwards tarred, but, rude as it was, it served its purpose for a number of years, and overcame an obstacle which materially interfered with the telegraph of that day.

Prior to Capt. Sleeth’s discovery it was necessary to string the telegraph wires from high poles across the rivers. On wide streams, like the Ohio, this was unsatisfactory because of the difficulty of stringing the wire high enough to prevent it being knocked down by steamboats at high stages of water. Then, again, the wire would frequently break of its own weight.

It is said that Professor Morse heard of Captain Sleeth’s cable and invited the latter to come to New York, where he explained his invention fully to the great inventor, and the present gutta-percha-coated cables that bind the globe are said to have been the result of Captain Sleeth’s rude Ohio river cable. He seems not to have placed a high value upon the importance of his discovery, but among his papers was found a letter from Professor Morse inviting him to come to New York for the purpose above mentioned.

The Omaha World Herald had a long story in its issue of 3 June 1895, by which time some comments had appeared on the March obituary. As well as reproducing the obituary, the Herald published two detailed letters in its story offering corrections to some of the statements made in the obituary:

FIRST SUBMARINE CABLE

Death of Captain Jack Sleeth at Paducah, Kentucky, Revives Some History.

He Once Laid a Crude Insulated Line on the Bottom of the Ohio River.

Prof. Morse Was Interested in His Work—The Old Pilot’s Death Caused Much Electrical Discussion.

A press dispatch about the middle of March informed the world that Captain Jack Sleeth, an old river pilot, had died at Paducah, Ky. He claimed to be the inventor of the insulated submarine electric cable. He was interested in the Nashville & St. Louis line, and it was found exceedingly unsatisfactory to string the wires high enough above the water, even of smaller rivers, to prevent them from being knocked down by steamboats, and it was practically impossible to do so in the case of the Ohio. He hit upon the plan of a submarine cable for the line which crossed the Ohio at Paducah to Brooklyn, Ill. The cable was a very crude affair, the wire being simply wrapped in bagging, which was then tarred. The experiment worked very well, and Prof. Morse, hearing of it, sent for Captain Sleeth. The captain met him in New York and explained his cable. Parts of the original cable are kept by a few people in Paducah as souvenirs, and other parts are still at the bottom of the river. Captain Sleeth is said to have had papers in his possession which proved the truth of his assertions, one being the letter in which Prof. Morse asked him to come on to New York and explain the workings of his line.

This dispatch moved several people to write to the daily papers relating what they knew of the matter. Mr. D. Huntington of New York City wrote as follows to the Evening Post:

In your paper of March 13, in an obituary notice of Captain Jack Sleeth of Paducah, Ky., it was said ‘In 1845 he erected the first telegraph in this section from St Louis to Nashville and conceived the idea of burying the wire under the Ohio river This was before the days of submarine cables.’ This conveys the impression that Captain Sleeth originated the idea of submarine cables. In September, 1837, in a letter to Hon Levi Woodbury, concerning construction of lines of telegraph, Prof Morse wrote ‘Where the stream is wide and no bridge, the circuit inclosed in lead may be sunk to the bottom,’ and again, referring to stretching the lines upon posts, says ‘This mode would be as cheap probably as any other, unless the laying of the circuit in the water should be found to be most eligible.’

In October, 1842, Prof. Morse, who had begun experiments several years before, constructed and on a moonlight night laid a cable between Castle Garden and Governor’s island, and transmitted signals, when the circuit was broken by the wire being caught by the anchor of a vessel setting sail, partly hauled up and carried off by the astonished sailors. Prof. Morse, as soon as he completed his rudely constructed recording electric telegraph in the winter and spring of 1835-36, began to apply its principles to submarine telegraphy, and declared his perfect faith in its eventual complete success. I was a pupil under Prof. Morse at that time, and witnessed his earliest experiments.

Then Mr C.C. Hine of 137 Broadway, New York City, wrote to the [New York] Sun on 30 March 1895, in part as follows

My attention having been called to a clipping from last Sunday’s Sun in regard to Captain Jack Sleeth of Paducah, Ky. as the inventor of the submarine cable, I venture to correct some of the statements therein, not for the purpose of robbing the gallant Captain of any of his laurels, but for the sake of accuracy in the ancient history of telegraphy in America. Your article speaks of the practical impossibility of taking a wire over the Ohio on masts, but this had been done some time before any telegraph wire ever reached Paducah. There are plenty of men still living who remember the masts at Jeffersonville and Louisville, on which the wire from Cincinnati went over. I myself saw those masts as late as 1850, at which date, and for three years before, the broader Mississippi was bridged by a wire strung from a mast on the Illinois shore to a shot tower in St Louis. At page 223 of J.D. Reid’s “Telegraphy in America” special mention is made of the first futile attempts to cross by cable. I was at that time an operator in the St Louis office and was not only personally cognizant of the facts, but assisted in laying the first cables across the Mississippi in 1840. For details reference is made to the above citation and Mr Reid’s book, at page 234, where mention is made of river crossings by masts over the Mississippi at Hannibal Keokuk, Rock Island and Dubuque, and over the Illinois river at Beardstown and Peoria.

In 1886 I read a paper before the Old Time Telegraphers which gives a detailed account of this early cable laying. That paper is among the archives of that association and is also printed in full on pages 466-470 of the Insurance Monitor for that year. I think the St Louis cable laying antedated any experiment that could have been made at Paducah, because the first (and for a year or two the only) telegraph line running south from the west was that of the Southwestern Telegraph company, from Louisville via Lexington to Nashville and on to New Orleans. This line was built in the summer of 1848, and it is not probable that any wire reached Paducah until some time later. It was certainly in 1850 that Colonel Tal. P. Shaffner got his line completed to St Louis from Nashville. I am therefore of the opinion that the superintendent of the Ohio & Mississippi line, J.N. Alvord, was ahead of Captain Sleeth in his submarine experiments, and even Alvord must have followed others, for the wire which he procured from the east was covered with three coatings of gutta percha expressly for submarine use, and was not made to order, but was at that time more or less a standard article, and it seems highly improbable that Prof. Morse was ignorant of this at the time it is alleged he invited Captain Sleeth to come from Paducah to New York to explain his bagging-covered, tarred wire cable

There was in the infancy of practical telegraphy a good many things ‘invented’ by different men, widely separated, who were confronted with the same difficulties, and I do not wish to detract a single lot from the honors of Captain Sleeth, but I am convinced that his recent biographer was not in possession of all the facts concerning the early river cables in the west.

The accounts of both Huntington and Hine point out many discrepancies in the story of the cable as written in the obituary and in the letter from Mr Warfield to the Sun.

Hine correctly notes that by the time the Paducah cable was laid in 1853, gutta percha insulated wire was a standard item, and Morse would have been well aware of it. About ten gutta percha insulated cables had already been laid in the waters around Britain by that time, and cable for use in the USA could have been purchased from the Gutta Percha company in London.

As early as December 1849 there was a report in the New York Post that Mr. S.T. Armstrong of the Hudson Gutta Percha Manufactory company of New Jersey planned to lay a gutta percha insulated cable from New York to Liverpool. In November 1849 it was reported that the firm had secured the sole patent for manufacturing gutta percha in the USA, and also in December the firm was offering Insulated Telegraph Wire at $65 per mile [both Newark Daily Advertiser]. This was followed in March 1850 by a proposal by a Mr. Armistead for a cable coated with gutta percha to be laid from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to the west coast of Ireland.

These schemes were almost certainly completely fanciful, and no further mention of either one has been found, but the news reports shows that as early as 1849 the use of gutta percha for insulating cables was well known in New York. And in its issue of 20 January 1852 the Daily Missouri Republican [St. Louis, MO] reported that the O’Reilly Telegraph Company had laid two wires across the Mississippi “insulated with gutta percha and then inclosed in lead pipes, but from some unknown cause one of them has already failed.” A Mr A. Wade was carrying out this work:

A number nine wire of the best quality, well connected and annealed, is covered with several coatings of gutta percha to the thickness of about three-fourths of an inch—to protect this from drift wood, snags, floating ice, sand, chafing against rocks and other like causes, the whole outer surface of the gutta percha is covered with number ten annealed iron wire, running parallel with and confined thereto, in a round cable formed by iron war bands within six or eight inches of each other—the whole weighing about eight thousand pounds to the mile, and possessing a strength equal to a three-quarter inch bar of solid iron.

Despite the corrections to the anecdotes about Sleeth’s cable which were published in 1895, an article in Scientific American’s issue of 23 June 1900 repeated many inaccuracies. The text below is from a copy of the Scientific American article which was published in The Electrical Review [London, 13 July 1900].

The First Submarine Cable

by W.F. Bradshaw, Jun.

The first successful application of submarine telegraphy undoubtedly was due to Cyrus W. Field, of New York. But the idea and the first practical application of it, as Mr. Field himself has generously acknowledged, must be credited to John Boyd Sleeth, a Tennessee River steamboat captain.

Captain Sleeth was born at Allegheny, Pa,, November 21st, 1826, and died at Paducah, Ky., March 12th, 1895. For several years he was on one of the old “broadbow” boats that plied on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Then he settled at Paducah, and in 1845 was in the employ of Mr. Tal Shafner, who had charge of the telegraph line at Paducah, which connected St. Louis and Nashville. The Ohio, at Paducah, is something over a mile in width, that being the point of its confluence with the Tennessee. The rivers meet at an acute angle, and the backbone ridge between them breaks opposite the city into two islands. It was by means of one of these islands that Mr. Shafner found it possible to run his line across both rivers. He erected tall staffs, one on the Kentucky shore at Paducah, another on the islands, and a third on the Illinois shore. The wires of the line across the Ohio at Paducah were strung upon lofty poles high above the stacks of passing steamers, which cleared the line in low water seasons, but struck the sagging wires and tore them down when the rivers rose. Great difficulty was experienced in keeping the wires sufficiently high and taut to avoid such accidents. Young Sleeth knew something of the principles of insulation, and the idea of laying an insulated wire across the river bed occurred to him. His idea was received with some scepticism by Mr. Shafner until he proved its feasibility by experiment. About a year later the local management consented to let him make the experiment of running an insulated wire across the river. The work of insulating the wire was slow and uncertain; little was known about insulating materials, and the workmen were “day” labourers, entirely ignorant of the nature of the task, who had to be watched incessantly. One of the eye witnesses, Captain Wes Cooksey, has given the following description of the manufacture of the first submarine cable:—

The wire chosen for use as the cable proper, one strand, was stretched along the float and wrapped first with canvas, such as was then used for roofing steamers. The canvas had been soaked thoroughly in hot pine tar pitch. The covering process was continued until the wire was about half an inch in diameter and then it was guarded by a wire of a slightly smaller size, this being placed parallel, as is now the custom. It was then wrapped by loose coil with another wire of the same size. The number of wires laid parallel to the cable outside of the canvas insulation was 18. The cable was made in sections, which were joined before being laid. Just how long it took to complete the insulation is not known, but it was several months. The cable was over a mile long, and when laid was reeled off from the end of a large “broadbow” boat in tow of a steam craft. The work of laying was attended with some difficulty and required several days. The first test was very successful, and the wires worked admirably for several weeks; then the pitch insulation, of course, became water-soaked and the cable began to “stick,” as the operators say, and was soon abandoned as worthless. But the idea had proven practicable, provided a better insulation could be found. Some months later Mr. Field sent a representative to Paducah to see Mr. Sleeth. An offer was made him to continue his investigations, and form a partnership. Mr. Sleeth was then in very moderate circumstances and had to decline the offer. The local management went back to the overhead wire, and the unsuccessful cable was soon forgotten.

Mr. Sleeth returned to boating, and was soon after made captain of a Tennessee River steamer. He fought through the civil war in the Confederate service under General Roddy, and came out a captain. After the war he went back to the river. Strange to say, he never patented his cable, or made any attempt to do so, but abandoned it entirely after the first failure. Mr. Robert Sleeth, of Pittsburg, Penn., wrote to Mr. Field in 1891, asking him about the truth of the report of his having sent a representative to see the captain, Mr. Sleeth’s brother, and discuss the idea of an insulated cable. Mr. Sleeth has the letter Mr. Field wrote in reply, acknowledging the facts as stated. About three years ago the end of the cable was found on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River, during the low water in August, and the accompanying illustration is a photographic reproduction of a piece filed off and now in the possession of Mr. James B. Sleeth, of Paducah, son of Captain Sleeth.

A Portion of the First Submarine Cable |

There are a number of discrepancies in this article.

The writer gives 1845 as the date of Sleeth’s first involvement with Tal Shaffner in landline telegraphy in Kentucky, when Sleeth would have been just 18 or 19 years old, describes the crossing of the river using a suspended cable as occurring at that time, and credits Sleeth with an underwater cable “about a year later”.

Shaffner and Sleeth were not associated until the formation of the St Louis and New-Orleans Telegraph Company in 1849, of which Shaffner was President. The Ohio River was crossed using a suspended cable in 1850, and Shaffner and Sleeth’s river cable was in 1853.

The chronology of the article would have Cyrus Field consulting Sleeth in 1847. But even as late as July 1853, while Shaffner and Sleeth were laying their documented cable at Paducah, Cyrus Field had no thought of telegraphs. He was in the middle of an extended tour of South America with the painter Frederick Church; they left New York on 7 April 1853 and returned on 29 October of that year. It was not until January 1854 in New York that Field met Frederic Newton Gisborne, who was building a telegraph line across Newfoundland and needed backers. Field conceived the idea of continuing the line across the Atlantic, and consulted with Samuel Morse on the feasibility of the project; Morse answered in the affirmative. All of Field’s dealings after that were with the well-established British cable makers.

As an aside, the article also credits Cyrus Field with the “first successful application of submarine telegraphy,” which is outright nonsense; by the time Field’s partially successful Atlantic cable of 1858 was laid there were already dozens of cables in service around Europe and elsewhere.

The cable described in The Electrical Review, the illustration of which is repeated below for easy reference, is purportedly a section of Sleeth’s 1847 cable recovered from the Ohio river around 1897. However, the description of the cable in the article:

The number of wires laid parallel to the cable outside of the canvas insulation was 18.

corresponds exactly to the published account of the 1853 Shaffner cable, as does the illustration:

...around this are eighteen large iron wires, drawn tight as the wire will near, and the whole it then spirally lashed together with another large wire passing around at every three-quarters of an inch.

A Portion of the First Submarine Cable |

Tal Shaffner's own account of the river cables:

In 1859 Tal Shaffner related the story of the development of his submarine cables for river crossings, the impetus for which was the destruction within a short period of several masts used for the overhead lines [Telegraph Manual, 1859, p599]. The cable described and illustrated by Shaffner is quite clearly the same as the one recovered from the river in 1897 and attributed to Sleeth.

DISASTERS TO MAST CROSSINGS OVER RIVERS.

The crossing of the rivers by the use of high masts, in America, proved to be unreliable and very expensive. Very often the wires would break and others would have to be substituted. High winds, sleet, snow-storms, and even frost, were severe enemies to the wires. The time required for the repair sometimes amounted to a day or more. Such fatalities bore heavily upon the prosperity of the telegraph. The public, ever restless to complain, could not appreciate the difficulties encountered. The people, however, was not so much incommoded as the treasury of the telegraph company.

…

The mast constructed on the island at the crossing of the Ohio river was swept away by the great flood in January, 1851. Soon after that was repaired, some evil-disposed persons cut down the one at the Tennessee crossing. A few days thereafter the one on the Illinois side of the Ohio river was destroyed by a hurricane; and a few weeks thereafter the great mast on the Kentucky side, 307 feet high, was torn to pieces by a tornado. The five masts just mentioned were erected and destroyed within a space of six months.

ADOPTION OF SUBMARINE CABLES.

It was during these misfortunes that my attention was called to the practicability of submarine crossings. Gutta-percha insulated wire had been found to be successful in tide-water streams, but to meet the powerful currents of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers no plan had been devised commensurate with the circumstances. During low water I had submerged No. 10 iron wires covered with three coatings of gutta-percha, but they lasted but a short time. The sand that thickens the water of the Mississippi river would wear off the gutta-percha and leave the iron wire bare. I found many such interruptions. In order to protect the insulation from being thus worn off, I had it covered with three coatings of osnaburg well saturated with tar; and in order to hold the osnaburg on the insulated wire, I had six No. 10 wires lashed to it the whole length, laid laterally. These wires were then tied, by lashing around them a No. 16 iron wire about every twenty inches. When this cable was laid, like all the rest, it worked well for a few months and then failed for ever. Soon after this effort was made, Mr. J.H. Wade was completing his line from the east to St. Louis. The crossing of the river was under the direction of Mr. Andrew Wade. I informed him of my experiments, and he concluded to cover the insulated wire entire with lateral wires laid on to the gutta-percha. They were fastened with ties of small wire at every twelve inches. He constructed the cable in that manner, and it proved to be a success.

THE SUBMARINE CABLES PERFECTED.

After this I had made several cables, with some additions to the plan adopted by Mr. Wade. Fig. 1 represents the cable as finally improved by me, in the perfection of which, however, I was aided by Mr. John B. Sleeth, an experienced mechanical engineer. Letter a, the electric conductor, is a No. 10 iron wire, made from the best Swedish bar, and drawn with great care, being capable of sustaining a strain of 1,300 pounds, b is the gutta percha insulation, being three coatings carefully manufactured. c the three coverings of osnaburg, saturated with a composition made of tar, rosin and tallow, d are the No. 10 lateral wires, and e the binding wire of No. 12 gauge, placed spirally around the whole cable. Several of these cables were laid in 1853, and some of them are being worked at the present time.

In manufacturing these cables we did not have the convenience of machinery and the variety of mechanical appliances common to populated countries. We were in the West, the great West, in the shades of the forest. The earth was our floor, the blue arched heaven our canopy, and the horizon the only limit of our saloon. Fig. 2 is a representation of the making of the cable. The reel is seen on the left. At the tree a wedge holds fast the finished cable. The men are engaged in putting on the binding wires. The circular board around which the lateral wires are spread is moved forward as the tie process requires. The board distributes the lateral wires around the electric conductor. The gutta-percha insulated wire, covered with the osnaburg, runs through a hole in the centre of the circular board. To avoid confusion, the insulated wire has been left out of the figure.

SUBMERGING OF THE CABLE.

When the cable has been finished it is ready to be submerged. The frame is erected in a boat and the reel suspended, as seen in fig. 3. The oarsmen then perform their task, and as fast as possible the boat is rowed across the stream. The cable is paid out as fast as necessary; but tho faster the boat traverses the stream the better and more certain will be the success. Sometimes it was possible to get small steam ferry-boats to tow the cable-boat across the river, but this could not always be done.

In 1904 a somewhat abridged version of the text of the Scientific American article from 1900 was reproduced in the book “Memorial Record of Western Kentucky” [Lewis Publishing Company, 1904, pp. 556-559], repeating the same errors and adding a further detail:

Robert Sleeth, a brother of our subject and resident to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, has a record from Mr. Field, of New York, stating that he obtained the idea of a submarine cable from Jack Sleeth, of Paducah, Kentucky, to whom he had sent a representative while he was residing in Paducah, to get this same idea, and this record Mr. Sleeth values very highly as it is to a certain degree a slight recognition of his brother’s great service to science and civilization.

When Cyrus Field developed his interest in the telegraph industry in 1854, any information he needed about submarine cables would have come from the well-established cable industry in Britain, with which he soon set up a business relationship. He would certainly have had no reason to ask Captain Sleeth about any aspect of cable making; especially not about a primitive cable which Sleeth was supposed to have laid seven years prior.

Paducah can justly take pride in having been an essential waypoint on the route of the St Louis and New-Orleans Telegraph Company, with a difficult river crossing made first by overhead line in 1850 and then by Shaffner and Sleeth’s underwater cable in 1853. And as Tal Shaffner notes in his authoritative account above, Sleeth’s skills as a mechanical engineer were important to him in perfecting the submarine cable during the laying of the cable at Paducah. But the claim that Sleeth “laid the first successful submarine cable in 1847” can not be substantiated with the documented evidence presently to hand.

Appendix A: Further embellishments.

In this 1910 account, Cyrus Field is in Paducah in 1847 to receive the first message over Sleeth’s cable:

Stone & Webster Public Service Journal

Vol 6, January-June 1910, p.

431

PADUCAH, KY.

Few people realize that Paducah is one of the leading historical cities of the South.

...

The first sub-marine cable in America was laid by Captain Jack Sleeth, across the Ohio River from Paducah to Brookport, Ill. The first sub-marine message in America was received by Cyrus Field, standing on the corner of Fourth street and Broadway, diagonally across from our office.

Even as late as 1913 there were new versions of the story appearing in the press. This article published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch issue of 8 June 1913 transferred the credit for the cable from Captain Sleeth to Orvin [actually Owen] W. Grimes and moved the date up to 1850:

How Paducah Man Made Subaqueous Cable for Friend.

O.W. Grimes Devised Telegraph Wonder of Age to Aid Guest at His Hotel.

An interesting story of how the first subaqueous cable was devised comes to the Post-Dispatch through an unintentional error on the part of a staff writer who journeyed to Paducah for the home coming there.

In telling of Paducah’s peculiar rights to fame, it was stated that Capt. Jack Sleeth was the man who devised the telegraph strand that made Cyrus K. Field famous and wealthy. Mrs. Margaret Grimes Murray writes to correct the name. It was Orvin W. Grimes, her father and proprietor of the hotel at First street and Broadway, she says, who devised the construction of the cable.

Mrs. Murray was, in 1850, a small girl and much in company with her father. She writes that she well remembers when Tal P. Shaffner, a partner of Cyrus K. Field, arrived there to superintend the connecting of their telegraph lines across the Ohio River, a step that was necessary to the prosperity of their business.

Shaffner’s first effort was to swing his line from a tall pole to Owen’s Island, but just as he thought success was his, the steamer Cherokee cams down on high water and her tall smokestacks swept the line into the river. Next Shaffner tried to lay his wire in the water, crossing the river at the tow-head. But driftwood that cams with a freshet broke the wire.

Shaffner was greatly discouraged when landlord Grimes sought [to] cheer him by a grouping of wrapped wires much as they are used in submarine cables today. Grimes designed his cable to be held to the bottom with sandbags. Shaffner saw the big idea at once and asked Grimes to lay the cross-river cable, which was done. In the meantime he wrote to Field, describing the cable. Field asked Grimes to send a sample of the cable to him, promising, Mrs. Murray says, to see that Grimes was properly repaid for any use that might be made of the idea.

That was the foundation of the marine cable, but Grimes heard nothing more from Field. Mrs. Murray says she wrote to Field many times, but never obtained satisfaction from him.

As noted earlier, Field had no association with Tal Shaffner in 1850, nor any involvement at all in telegraphy. This account seems to be a conflation of the actual events of 1850 through 1853 at Paducah and the (fictitious) story of Sleeth and Cyrus Field, with Sleeth being replaced by Grimes and Cyrus W. Field referred to as Cyrus K. Field.

Grimes [1799-1876] was well-known in Kentucky and merited an entry in “The Biographical Encyclopædia of Kentucky of the Dead and Living Men of the Nineteenth Century”, published in 1878, where his name is given as Owen, not Orvin. The entry notes that he was landlord of the Marshall House hotel in Paducah for five years from 1847, and gives this account of his supposed involvement with the telegraph enterprise there:

While first at Paducah, Mr. Grimes induced the citizens to have the telegraph extended from Cairo to Paducah, and subsequently from Paducah to Nashville. In doing this, two large rivers were spanned, the engineers in charge stretching the wires across the rivers upon supporters, which the steamers and drift-wood soon made away with. In this dilemma he urged a method which was found on trial practicable and successful, namely, to lay the wires upon the bottom of the river. He was thus, to some degree, the father of submarine telegraphy, for when, two years later, Cyrus W. Field and others were about laying two telegraph wires across the ocean, and failed therein, because the wires would not work, Mr. Grimes sent Mr. Field a model of his plans, and received in reply a letter from Mr. Field, stating that he had submitted his (Grimes’s) plans and model to his associates, and that the same had been approved and accepted, and he (Mr. Grimes) would hear from them. But he never did hear from them, other than the general news that the third wire was fully successful.

As with all the accounts of the Ohio river cable at Paducah, the chronology fails when attempting to put Cyrus Field in the story. Two years after the laying of the Paducah cable would put Grimes’s supposed communication with Cyrus Field as being no later than 1855. But the two failed "wires across the ocean" were in 1857 and 1858. And Tal Shaffner, in his account above of the 1853 Paducah cable, makes no mention of Grimes.

A 1942 re-telling of the story.

As should be evident by now, each new account of the story of Sleeth’s cable had its own “facts,” almost none of which were supported by any historical evidence. This version from the May 1942 issue of Waterways magazine was written by Paul Twitchell, a Paducah native who many years later achieved some notoriety as the founder of the Eckankar cult.

The only accurate details in this story are the date of Sleeth’s birth, the fact that he worked as a riverman in Paducah, and the notes on the 1866 Atlantic Cable. The information on both Samuel Morse’s and Cyrus Field’s involvement with the telegraph system at Paducah has no basis in fact; neither man was associated in any way, at any time, with the project. The only tenuous connection was that when Tal Shaffner was first involved with building the telegraph at Louisville, he contracted with the patentees of the Morse system for the rights to use that technology on his lines; as noted in the main article, it was Shaffner who first brought the telegraph to Paducah in 1849.

The photograph in the article (of the 1853 cable, once more) was by E. Earl Curtis, a well-known Kentucky photographer at the time the piece was written. Presumably the cable sample was owned by someone in Paducah at the time; it would be interesting to know if it has survived.

A River Man Invented the Submarine Cable

By Paul Twitchell

CYRUS W. FIELD spent a fortune on a submarine telegraph cable that would link Europe and America, and he completed it in the year of 1866, after many years of trials and tribulations. The cable was 1,864 miles long and was laid from Valentia Bay, Ireland, to Heart’s Content, Newfoundland.

But Cyrus Field was not the inventor of the submarine cable. A riverman by the name of John Boyd Sleeth, who lived in Paducah, Kentucky, actually created the first submarine telegraphic cable, and it was he who was responsible for Field’s later success.

John Sleeth went to Paducah in 1845, on a flatboat from Pennsylvania, where he was born in Allegheny in 1826. He arrived in that city at about the time of the invention of the telegraph by Professor Samuel B. Morse, who had then but recently sent the first message from Washington to Baltimore, over wires.

A section of the original Sleeth Cable

Photograph by E. Earl Curtis |

Professor Morse had run a long stretch of this cable from St. Louis to Nashville. It crossed the Tennessee and Ohio rivers, near Paducah, where it was connected on what is now called Owens’ Island, just at the city’s levee. But the telegraph wires were meeting with much difficulty and at every highwater stage river-packets, with looming chimney-stacks, always managed to tear them down.

Young Jack Sleeth had at this time become a riverman, working as a mate on steamboats out of the city. His ability was marked, and it was reported that he would be a captain.

This young riverman saw the possibility of solving the problem that was confronting Morse’s telegraphic company. He had been working on this idea for some time when approached by Tal Shafner, the company’s representative at Paducah.

Sleeth’s idea for a submerged cable was an immediate success. It was laid in the summer of 1847 and used for six weeks. The wires were carefully covered with gunny-sacks and tar, taken aboard flatboats and lowered to the bed of the river.

News of his activity reached Cyrus Field, who had already failed in trying to lay a submarine cable to Europe. A representative was sent to Paducah to watch the proceeding, and it was only after receiving the report of this agent that Field laid the first under-water cable from Jersey City to New York.

Meanwhile down in Kentucky, Captain Sleeth had developed some new ideas for his submarine cable and in the fall of 1853 he laid a two-wire cable across the river. Field heard of this and sent a man to investigate.

This agent’s report brought Field in haste to Paducah and when he left he had the plans of the cable. But Captain Sleeth could not be induced to join with him in the formation of the company then organizing to promote the Atlantic cable. He explained that he had to make a living for his family and had a good chance at steamboating.

The old Sleeth cable remained in the river until some years afterward when a flatboat pulled it up on the Illinois shore, hoping to use it as a towing cable, but found it to be too stiff and it remained where it had dropped for many years.

Captain Sleeth stayed on the river until his death in 1898. He now sleeps in the old city cemetery in Paducah without mark of recognition.

The first message that was sent across the ocean in 1866 to link the world was brought about by the efforts of a riverman who refused to believe in his own success.

Appendix B: 1963 documentation prior to the installation of the marker.

While the documentation at the Kentucky Historical Society for the 1963 marker is somewhat sparse by today’s standards, it does provide further details on how the wording for the entry about Sleeth’s cable was defined. I make some conjectures here which I believe are supported by the documents from the archive.

As noted above, the marker was sponsored by the Woodmen of the World Life Insurance Company, and installed during their state convention in March 1963. The content and wording of the marker must have been discussed several months in advance, so that the marker could be designed and cast in time for the convention.

The first document in the archive is a letter dated 4 February 1963 from Hall Allen to W.A. Wentworth, Chairman of the Kentucky Historical Highway Marker Program. Hall Allen was a historian, author and columnist for the Paducah Sun Democrat, Madisonville Messenger and Greenville Leader. His book on the Civil War, “Center of Conflict: a factual story of the War between the States in Western Kentucky and Tennessee,” was published in 1961, and at the time of his death in 1972 he was working on another book, “History of Kentucky,” which was never published.

Allen must have been asked by the Marker Program to research the topics to be included, but establishing the history of Sleeth’s cable proved problematical. Allen gathered information on Sleeth and his cable from local sources; his references were Fred G. Neuman’s 1927 book, “The Story of Paducah,” a short piece about Sleeth’s cable in a 1960 issue of the Kentucky State Bar Association’s Journal, and correspondence from the Smithsonian Institution about Paducah resident Miss Clare Winston’s piece of the river cable.

Miss Winston had evidently asked a history teacher at the Franklin Junion High School in Paducah to find out more about her cable, and the teacher had written to Bernard Finn, then Curator of the Division of Electricity at the Smithsonian Institution (and now, almost sixty years later [as of 2022], curator emeritus and acknowledged as the leading historian of the telegraph industry). Finn’s reply included the references to Tal Shaffner’s “Telegraph Companion” and “Telegraph Manual” which are reproduced in the body of this article, together with a copy of Shaffner’s sketch of the cable.

Hall Allen’s letter to the Marker Program summarized his findings and included supporting attachments:

PADUCAH, Ky., Feb. 4, 1963

Dear Mr. Wentworth:

Here is all the information I've been able to collect on Capt. Sleeth’s submarine cable. It leaves us quite far afield.

Since the Chamber of Commerce and the Woodmen of the World insist on the Sleeth thing going on the marker, the 1847 date probably is as good as any.

I therefore am washing my hands of the entire thing, convinced that we could never arrive at a definite date from the evidence available.

No trace has been found of a purported letter from Cyrus Field to Sleeth asking him to join in the laying of the Atlantic Cable. Miss Winston says Mrs. Sleeth told her there was such a letter.

You will please see that the date on the George Rogers Clark visit is changed from 1888 to 1878.

Cordially,

HALL ALLEN

Allen attached extracts from Bernard Finn’s letter, as noted above, and summarized his other findings as follows:

SLEETH

Mr. Tom Waller, president of the Kentucky Bar Association, could add no documented evidence in the case. He arrived at the 1837 date by subtracting 10 years from the date on the marker at Campbell St. (See Neuman’s account).

Miss Clare Winston, who owns the piece of cable says it was given to her by the widow of Capt. Sleeth. She said she got the story from Mrs. Sleeth and all her information is based on her recollections of the story. She does not dispute the 1847 date, because her recollection might not be right. In other words, she actually doesn't remember.

The Kentucky Bar Association column, published in 1960, could hardly have been useful, as almost every statement in it is wrong. And as Allen notes above, the president of the Bar Association, Tom Waller, “could add no documented evidence in the case”.

Here is the text of the column, also from the Kentucky Historical Society archives:

Kentucky State Bar Journal [1960]: Inventions, page 8

At the foot of Campbell Street in Paducah on the bank of the Ohio River, Capt. Jack B. Sleeth ran his submarine cable across the Ohio River to the Illinois shore in 1837. It was supposedly the first successful telegraph submarine cable and was later acquired by Western Union. For twenty-one years after the laying of this cable Capt. Sleeth lived in Chicago and worked with Cyrus W. Field who in 1858 laid the first transatlantic telegraph cable for the Western Union Telegraph Company. At the end of the twenty-one year period in Chicago, Capt. Sleeth returned to Paducah and died there.

These are the factual errors in the column:

It dates Sleeth’s cable to 1837 (seven years before Samuel Morse erected the first telegraph line in America) and reports that it was later acquired by Western Union, which did not exist until 1855. It says that Sleeth moved to Chicago after laying the cable in 1837 (when he would have been just ten or eleven years old) and spent 21 years there working with Cyrus Field (who in the meantime was employed in Manhattan as a 15-year-old errand boy and subsequently became a very successful and wealthy paper merchant there). It credits Field’s 1858 Atlantic cable to Western Union (a company involved only with land lines at the time). And finally, it has Sleeth returning from Chicago to Paducah in 1858 and dying; in fact, aside from his few years around 1850 in the telegraph industry at Paducah, he lived and worked most of his life as a riverboat captain in Kentucky and Tennessee right up until his death in 1895.

It’s not clear why Waller changed the date of the cable to 1837 in this column; it was perhaps a misreading of a statement in Fred G. Neuman’s 1927 book (text from Kentucky Historical Society archive):

The Story of Paducah, Fred G. Neuman, page 96

From this point (foot of Campbell Street) Capt. Jack B. Sleeth ran his celebrated submarine cable to the Illinois shore in 1847—the first successful under-water cable used by the Western Union Telegraph Company.

Unfortunately the tablet at the foot of Campbell street sets the date of this experiment ten years later than it really occurred.

Allen notes in his letter that: “[Waller] arrived at the 1837 date by subtracting 10 years from the date on the marker at Campbell St.”

However, I interpret Neuman’s second paragraph to mean that the Campbell Street “tablet” (presumably the predecessor of the 1963 marker) had the date of Sleeth’s cable as 1857, while Neuman believed it should have been 1847. This is confirmed by the somewhat more detailed text in a copy of the 1920 edition of Neuman’s book at the New York Public Library:

FIRST SUBMARINE CABLE

In these days when mighty arches span the great inland waters it is quite inconceivable to place cables with their multitudinous and sensitive wires at the river’s

bottom. Wherever a bridge crosses a river, telephone and telegraph wires are found above; but sixty years ago

these spans were considerable distances apart necessitating laying the insulated wires under the water. In this connection a tablet placed at the foot of Campbell street is of unusual interest, telling as it does of the first cable laid across the Ohio at this point. The tablet bears this

inscription: "From this point started the submarine cable, made and laid by Captain Jack Sleeth, for the Western Union Telegraph company in 1857."

By present standards, the level of evidence in this correspondence falls far short of that required to justify a historical marker, and Allen quite understandably wrote that “I am washing my hands of the entire thing.” But as Allen also noted in his letter, there was strong local pressure to include Sleeth and his cable, no matter how slight the case for the 1847 date, and the Marker Program acquiesced in this reply from W.A. Wentworth, the program’s chairman:

February 6, 1963

Mr. Hall Allen

Paducah Sun Democrat

Paducah, Kentucky

Dear Mr. Allen

The product of “washing my hands” with regard to the submarine cable is received. I think this clears up pretty well for completing the draft of the inscription for that marker.

I note that the reference to George Rogers Clark should carry the date of 1878.

Yours very truly,

W.A. Wentworth, Chairman

Kentucky Historical Highway Marker Program

My conclusion from this correspondence, and from the other evidence presented in this article, is that the story of Sleeth’s cable was entirely anecdotal by the time of his death in 1895, and it was then further embellished by each successive writer until it lost almost all connection with historical fact. The only documented cable is the one laid by Shaffner and Sleeth in 1853; if Sleeth ever experimented with a cable before that, all records of it have been lost.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to the Kentucky Historical Society for providing copies of the documents in their archive related to the creation of the 1963 historical marker, and for permission to reproduce the text of the documents in this article. The Society’s support added greatly to the modern history of Captain Sleeth’s story.

|

|