| WESTERN UNION CABLE STATION, PENZANCE

Western Union leased two cables laid in the 1880s by CS Faraday (1) for the American Telegraph and Cable Company which had been set up by Jay Gould. The cables ran from Canso, Nova Scotia to Sennen Cove, Cornwall. From Sennen an underground cable was laid to Trewithen Road in Penzance, where WU had purchased a house to use as its cable station.

In 1912 the company also leased all of the Anglo-American company’s transatlantic cables; these terminated at Valentia in Ireland. In the same year the company engaged architect Henry Maddern to design and oversee the building of a new station on land in Alverton Road next to The Sycamores.

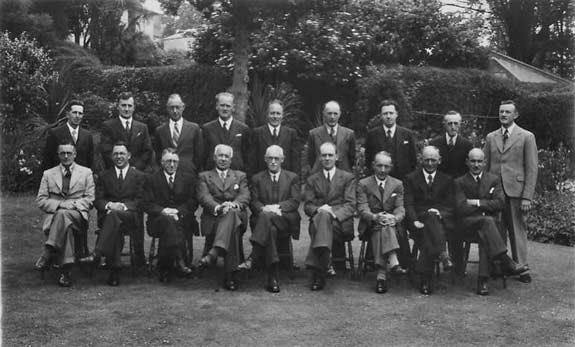

Cable Station, Penzance c. 1925

Western Union Archives |

In 1918 a cable was laid from Valentia to Sennen Cove, allowing traffic to be routed to Penzance and in 1926 a loaded cable was laid between Sennen Cove and New York.

A condition of Western Union’s takeover of the Postal Telegraph Company in the USA was that the company had to dispose of its international cables. This didn’t happen until 1963 when a separate company, Western Union International, Inc., was set up. At the same time WU terminated its leasing arrangements with the Anglo-American Telegraph Company. In 1966 it abandoned its cables running via the Azores.

Western Union Staff, Penzance, July 1946

Image courtesy of Ken Wood

Thanks to John Bottle for staff IDs

and

Dennis Blount for the ID of Ernest James Blount

| Sam ?? |

Ben Thomas |

Wilfred N Wood |

Harold E Chivers |

Dick Alleary |

F H Standen |

Matthew E Rowe |

Jim Trewhella |

Harold G Tutt |

| E John Batten |

Lionel E Gridley |

"Jack" Corin |

John H Coghlan |

Ernest James Blount |

John C O'Flynn |

Charles Brown |

Reginald Morrish |

Harold Ellis |

|

Dennis Blount sends this newspaper account of a happy occasion at the station:

The Cornishman and Cornish Telegraph, 31 Aug 1921

A very pleasant ceremony took place at the Western Union Cable Station, Penzance, on Thursday afternoon. The celebration was a joint presentation made by the members of the Penzance staff to Mr. E.J. Blount, supervisor, and Miss N. Edwards, lady supervisor, in honour of their approaching marriage. A large number of friends and colleagues, including as many as could be spared from duty, ssembled in the restaurant room of the building.

The gift itself consisted of a handsome writing bureau of antique design and was presented by Mr. T. O'Donoghue, superintendent Penzance station. In the course of a very interesting speech, Mr. O'Donoghue referred to the efficiency with which Miss Edwards had always carried out her duties and her popularity with the staff. He also paid a glowing tribute to Mr. Blount’s sterling qualities and moral courage, adding that he was sure the approaching union would be a most happy one. “This token of remembrance and respect,” added Mr. O'Donoghue, “in no way measures the great esteem in which both are held by the entire staff.” Speeches were also made by Messrs. J.C. Truscott, C.T. Pounsford, J. Barr, and S.G. Harmer.

Mr. Blount, replying briefly, said he was quite overwhelmed with the handsome gift and the kind thoughts associated with it. Miss Edwards recorded her high appreciation, adding that the present will always remind her of the many happy days spent with all. A hearty vote of thanks was proposed to the chairman, and the proceedings terminated amid hearty cheers. |

After the closure of the cable station the building was sold off and subsequently became a hotel then a nursing home. It was finally divided up into flats, but its appearance remains substantially unchanged.

John Bottle, who was an apprentice at the station in 1948 and worked there until 1963, adds these notes:

The Penzance Cable Office building was beautifully built, and designed just for the purpose. When it was built, "hot-wire amplifiers" were used to amplify the cable signals (it was before the age of thermionic valves), but they were mechanical devices and would be disturbed by nearby vibrations such as people walking around or traffic on the road outside. So several concrete pillars were built, standing on the basement foundation and extending right up to the upper floor, so that the hot-wire amplifiers could sit on them and be isolated from the movements of the building. I often wonder what the later users of the building made of those!

The Western Union cables left the cable hut at Sennen Cove and snaked across the lovely beach to the sea. Depending upon recent weather, the cables were often exposed. One story is that a member of staff was on the beach one day and saw a loop of cable being used to hang a holiday-maker's kettle of water over a stove for making tea!

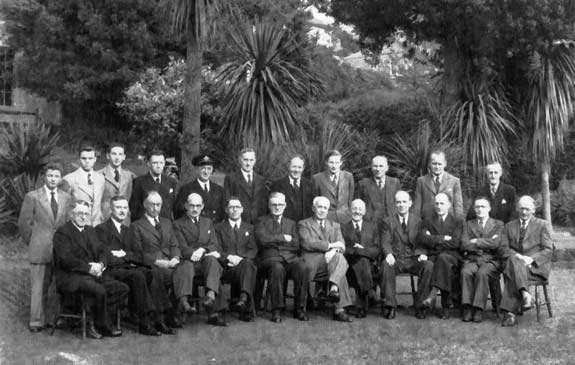

Western Union Staff, Penzance, 1951

Image courtesy of Maurice Pellow

Thanks to John Bottle for staff IDs

| Nat Dann |

Hugh O. Cocking |

W. Maurice Pellow |

Matthew E. Rowe |

Henry Nicholas (peaked cap) |

Ben Thomas |

Dick Alleary |

Raymond Clulow |

George James |

Harold E. Chivers |

Jim Trewhella |

| "Jack" Corin |

Harold G. Tutt |

Wilfred N. Wood |

Harold E. "Sam" Ellis |

Lionel E. Gridley |

Frank Curnow |

John H. Coghlan |

L. C. Smyth (Head Office London) |

John C. O'Flynn |

F. H. Standen |

E. John Batten |

Reginald Morrish |

|

John Bottle adds this further note:

I am not in the picture because in 1951 I was doing my 2 years National Service with the R.A.F.

Henry Nicholas was a full-time employee of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution at Sennen Cove, where the W.U. cables came ashore. I think he was the lifeboat engineer, but he also looked after the W.U. Sennen "Cable Hut" (actually a well-built granite building.) Every day he would phone through with various readings and he was a good source for forecasting our weather. He had a lovely Cornish accent.

Western Union in Penzance, 1898

Below is an extract from an article written by “The Spectator” in the 15 October 1898 edition of the weekly magazine New Outlook:

Most readers have, no doubt, had occasion to cable occasionally, those who are business men frequently. But the Spectator wonders how many of them have actually seen the cable “in operation” —that is, the operation of receiving and transmitting messages over it. The popular idea of a cable station (at least it was the Spectator’s) is that of some lonely station at some practically uninhabited point, where the cable operators spend their days in very much the same isolation as do lighthouse keepers. Doubtless there are cable stations which answer to this description; at least the Spectator has been so told by his friends, the telegraph operators. The cable station which he himself saw, however, was not on the shore at all, but all of ten miles away from the point where the cables were landed. There was another temporary station at the point of landing, which the operators could work effectively in case of needed repairs, or if the shore end of one of the cables got out of order. The station in question was that of the Western Union in Penzance, a town of some thousands of people near the Cornwall coast of England. The house was like any other house, an old residence made over, and there was nothing about it except the sign to advertise its unique use. The room, too, where the operators were at work was in no striking way different from any room used for telegraphic purposes. The difference was principally in the fact that the operators did not “follow the ticker” on typewriters — in fact, did not copy off the sounds as they were transmitted, but transcribed the messages on rolls of sensitive paper soon covered with old-fashioned dots and dashes, just as used to be the case at ordinary telegraph offices before the days when operators became so expert as to read by sound.

The Spectator was told that this was not entirely due to the feebleness of the current over the thousands of miles of cable under the sea, although this was one reason for it. Many cable messages are transmitted in cipher, and of course the sentences make next to no sense. As a mistake in the message might cost the company a large sum in damages, the utmost accuracy is necessary, and this can be attained much more surely with the record of an automatic Instrument than through the ear of the operator. As operators must get used to all sorts of queer things, the Spectator was surprised to see one of them laugh as he copied off a certain message. By permission of the manager, who also seemed surprised, the Spectator had a chance to look over the operator’s shoulder to see what it was that had brought a smile to his usually impassive face. The message came from some city in interior New York, and read something like this: “Darling: I cannot live without you. I think of you every night and morning. How much longer must we be separated?” The Spectator wondered a little whether this was a genuine message of affection from one lover to another, at a cost of twenty-five cents per word, or perhaps simply a code message, referring to some “wheat deal” or stock speculation. He never learned the fact, but has always been rather of the opinion that this distantly extravagant love-making was to be set down to an ardor that did not reckon the expense. While in the cable office there were shown to the Spectator the old appliances of lights and mirrors by which messages used to be transmitted in a darkened room before the present days of improved cables and increased strength of currents, when different words were denoted by the length and character of the flashes. This method, so he was told, was still resorted to at times when the feebleness of the current prevented the use of the ordinary instruments.

A thing which interested the Spectator very much was the constant communication which was kept up between that office in Penzance and the cable repair ship which then was somewhere across the ocean in the vicinity of Newfoundland. Such is the delicacy of the scientific tests that when a cable is “broken,” as it is called, it is possible to determine within a mile, perhaps within even a half-mile, the point of breakage. All the repair ship has to do is to go to that point and grapple there for the end of the cable. With that on board, the ship can, communicate with the home station as easily as operators can. send a message over a press wire between two distant points. In fact, daily and often hourly messages are sent, and the managers of the cable company know just how soon the cable will be in working order. The idea appealed to the Spectator vividly. There was the repair ship off the coast of Newfoundland, perhaps hidden in a fog, perhaps buffeted by a storm, perhaps with no land or other ship in sight, and yet able to send messages as easily and quickly and frequently as if the two points of connection were on shore. The thought suggested is perhaps fancifully impracticable, that sometime it may come about that ocean steamers will go out carrying cables with them, and thus be in constant communication with the land, even in mid-ocean. Should such a time ever come, the Spectator wonders whether it will not really see the end of one of the advantages of ocean travel — the complete rest that comes from the feeling that for a certain number of days one is entirely cut off from connection with the civilized world; that, whatever happens there, one is powerless to do anything, and must therefore drop worry and throw off anxiety. When Horace tells how “black care” follows the traveler across the sea, he surely does not mean that the ordinary cares of ordinary life can follow one during the time of voyage. Anxiety there may be, but not the continual worry that frets the soul. That is the blessed relief which comes when one loses sight of land as the steamer or ship moves out into the ocean.

|