|

Introduction: Leone Banks shares this

story from her grandfather, Charlie Banks, who served on CS Minia during a cable repair voyage in 1894. The Minia was the repair steamer of the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, which owned and operated several cables between Newfoundland and Ireland at that time, and the repair was to the Atlantic cable of 1874 (see note at end of story for further details).

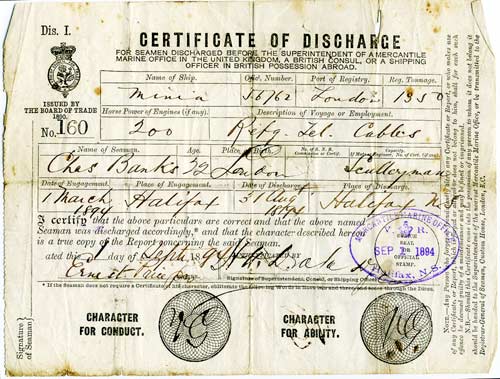

Born in London to a Baptist pastor in 1877, Charles Banks emigrated to Halifax, Nova Scotia in the summer of 1893 at the age of 16 after the death of his mother. Discovering that he disliked farm work after a bad experience in the Annapolis Valley of Nova Scotia, Charlie hitchhiked back to Halifax and signed on as a sculleryman with the Minia on 1 March 1894, when he was 17 (although according to his Certificate of Discharge he gave his age as 22). On board ship he encountered perhaps more than he had bargained for, and his description of the voyage is below.

After some other adventures at sea and on land, Charlie settled down in Canada, eventually homesteading in Manitoba's Swan River Valley in 1898.

|

Fire at Sea

Charlie's memory of a fearful experience

Early one morning on the 1st of March 1894 I had been hired on as a kitchen helper on the S.S. Minia as it sailed out of Halifax harbour, on a regular routine job of repairing broken telegraph cable. The Minia was at one time in the China tea trade and later had been sheathed with iron and fitted out with steam power. She still carried sails and the crew were all hardy seamen, mostly from the fishermen of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. As in all cable ships she was heavily loaded on her upper decks with buoys and gear while below in the holds in circular tanks the cable was coiled.

Charles W Banks in 1912 |

About a week later the first end of the break was located and this being caught with a grapple was soon brought to the surface and attached to one of the buoys. Then the search for the other end was started. The weather had been getting quite rough and soon it broke into a gale. All openings were battened down and the ship settled down to fight it out with the storm. During the night the crew who were off duty were startled by the Boatswain shouting for “all hands on deck”. Boatswains always seemed to have voices like thunder, and this one was the master of them all. The first itimation of the reason of the call was the smell of smoke and it seemed to come from every opening. Imagine, if you can, the fear that would grasp your heart if you were caught in your home with it afire and no way of escape. Well this is like what fire on board a ship is and it takes men of stout heart and indominitable courage to face it. The boilers of this old ship had been covered with wood and possibly through having to keep up full steam pressure and with everything being battened down had caused the dry wood to ignite. For forty hours every man of the crew fought desperately to put out that fire and also to feed the fires under the boilers so that we would not drift onto the rocky shores of Labrador. Man after man was pulled up out of the stokehold, some were almost unconscious and some were badly scalded. There was no sit down strike here but every man doing his utmost to save the ship. At last the fire was brought under control. No words can describe adequately the physical suffering of these men.Just a bite to eat, a few minutes rest, then back to work until exhausted.

One would expect that now the ship would be headed for home but such is not the way of the sea. A duty had to be performed and still the ship was headed into the mountainous seas riding the storm until it abated. For almost a month this was continued before the storm had worn itself outthen once again the Minia was put back to search for the other end of the broken cable. Some five hundred miles off her course it took two days to get back. Grapples were lowered and it was not long before the cable was located and the end brought on board to have it spliced onto the cable in the hold. Once again she was on her way to the other end , this was spliced, and amid great rejoicings, and a drink of rum as a toast to a job complete, the cable was dropped overboard and the Minia's nose turned toward home. On an early July morning, with food supplies almost exhausted and only a few shovels of coal left she steamed into St. John's Harbour, Newfoundland. The twinkling light of the city were a welcome sight, and the drab old ship had once again done its job.

Charlie worked on the SS Minia until the end of August 1894.

Certificate of Discharge from the Minia for Chas. Banks, 31 August 1894 |

The Minia was commanded for many years by Captain Samuel Trott; a book written in 1895 by D.W. Prowse, A History of Newfoundland from the English, Colonial and Foreign Records, page 646, describes him as follows:

The Anglo-American Co. possesses most devoted and valuable servants; none of them are more remarkable than the captain of their cable steamer Minia, Samuel Trott. John W. Mackay correctly designated him “the greatest cable-catcher in the world ”; no difficulty, no depth of ocean, can keep the

cable from his grasp. His latest feat, in the summer of 1894, in grappling and splicing successfully the two ends of the seventy-four cable, over 200 miles apart, in 2,700 fathoms of water, with a current running six knots, is the crowning achievement of his remarkable career.

From this we see that Charlie Banks' expedition on the Minia was to repair the 1874 cable from Valentia, Ireland, to Heart's Content, Newfoundland. This had been laid by Great Eastern, with the assistance of Minia. From the description of Captain Trott given above, it's obvious that a little fire on board ship would not have deterred him from continuing the expedition, as Charlie Banks tells in his story.

A December 1894 interview with Captain Trott from a Boston newspaper, reprinted by The Electrical Engineer in its issue of 25 January 1895, page 111, gives further details:

We have been favoured with a copy of a Boston paper bearing the date of December 10, 1894, and containing a report of an interview which a representative of that paper had with Captain S. Trott, of the Minia. The following extracts will be read with interest:

“The business of cable repairing,” Captain Trott said, “is a science in itself. It would take hours to explain the thing thoroughly. You have asked me several questions, none of which are easily answered. You spoke of anchoring at sea. We do not anchor. To start with, supposing we are ordered to repair some break. We get the location as near as possible from those on shore, and proceed to the spot. We then lay about and place a buoy in position. The ship is kept under steam while we are there, and we keep our position as well as possible. We then take soundings to see what the bottom is like, and then drag for the cable with a grapnel until we hook it. Mind you, if the cable is in deep water that cannot be done. You cannot hook it and pull it up, because there is not slack enough to bring a bight to the surface. The cable, therefore, must be cut or broken unless we can get near enough to the break and pull up one end. Now, all this sounds very easy while I am telling you about it, but when you come to do the thing it is a different matter entirely. Allow me to give you an example. In July, 1893, one of the Anglo-American cables—the company I am employed by—broke. At the time I was out repairing one of our cables, one of the oldest by the way, having been laid in 1869. After completing my work I went to England for more cable to repair another break. When we got part on board our 1874 cable broke (you see we name our cables by the year they are laid), and another ship was hired to go out and repair it. She took the 100 miles of cable destined for us, half of which we had on board. We had to remain in England until another 100 miles were manufactured for us.

“In the meanwhile the Calabria, double the size of us, had gone to repair the 1874 cable. She started in July [1893], and was over 100 days at it. Once during that time she lifted one end, spoke the shore, and spliced one piece of new cable. When they commenced to pay out the cable broke, and, if my memory serves me right, it was on board ship. They lost it, and never recovered it again for that year. It sunk in 2,400 or 2,500 fathoms of water. There's one example for you. In October I was in St. John's and was ordered to proceed to England, I having told the manager that it was impossible to recover the cable that year. The Calabria also went to England, the manager having agreed to what I said. All they had done was to break pieces off. This summer [1894] we were ordered to do the work and we did it. It has been our summer's work. Beyond doubt it was one of the most important ever accomplished.”

“You are right, captain,” an officer broke in; “and if you have too much modesty to say anything, I have not. They sent Captain Trott,” he exclaimed, “because he never in all his life has failed to accomplish anything sent on.”

“Well, that's neither here nor there,” resumed the captain. “ We were in lat. 49.50 and long. 40.30, so that'll give you some some idea of where we lay. We went to work in May, about the 20th, and it took us till nearly the end of July before we had completed the work. We had a lot of nasty weather, and one of the greatest difficulties I ever encountered, and one that I had least expected, was a strong stream running to the north-east. We, however, managed to complete the work, and that's all that need be said about it, The Faraday, I learn, has put into Penzance, England, within a week. She was on one of the Gould cables, which is leased by the Western Union. She was working in long. 40, somewhat further south than we were. She failed. Like the Calabria, she got one end, and that's all. They wanted me to take that job, but I was of the opinion that it could not be successfully performed. I have been engaged on different cables lately, and have just finished work on the Duxbury cable.”

If any site visitor has further information on the fire on board Minia in 1894, please email me.

New York Times, Mar 17, 1899.

Capt. Samuel Trott.

Capt. Samuel Trott, who died at Miami, Fla., on March 11, was commander of the Anglo-American Cable Company's steamer Minia. He had suffered from heart trouble, and had been spending the Winter in Florida for his health. His body was brought here, and was forwarded on the steamer St. Paul to England.

Capt. Trott was born in Sussex, England, in 1832. He had spent just half a century on the ocean, having gone to sea when he was seventeen years old. He was a master ten years later. After several years, during which he commanded vessels in the trade between the United Kingdom and South America, he took command of the cable-laying steamer Faraday in 1874. He laid the French cable and the direct cables, and made a record in cable repairing, demonstrating that the work of repair could be done in Winter as well as in Summer.

He was placed in command of the Minia in 1880. It was in this vessel that he laid the cable for the United States Government between Key West and Dry Tortugas, just prior to the late war.

Capt. Trott invented a number of devices used in deep-sea cable work, including an electric grapnel in which a bell is rung aboardship when the grapnel touches the cable. He was also the joint inventor of a new cable.

|