Introduction: Betty and Bob Kellogg share this interesting

oral history from Bob’s grandfather, Walter (Wilkie)

Claypoole, who worked at the Far Rockaway (Long Island, NY) and Canso (Nova Scotia) cable stations during the First World War.

If any site visitor has more information on the Far Rockaway cable station or Walter Claypoole’s cable work, please email me.

|

Walter Claypoole

Walter Claypoole was born in Sneinton, Nottinghamshire, England on 24 November 1872. His career spanned his installation of the first electric lights in Loughborough, Leicestershire (his then home town) when he was 18, to working on friction experiments and thermocouples at Columbia University in NYC which, unbeknownst to him at the time, were relevant to the Manhattan Project.

Some time after moving to New York in 1911, Walter had met Charles Priest, Chief Electrician of the Commercial Cable Company, and was employed by the CCC during the First World War to work on improving signal shaping for long undersea cables. He also visited the company’s Canso cable station in Nova Scotia during this period.

After his retirement in 1958 at age 86, when Walter was beginning to lose his sight, his daughter bought a “newfangled” reel to reel tape recorder for him to record his life’s story. A wonderful raconteur, he had enchanted his grandchildren with these stories when they were little – and even after nearly 50 years in the US he had never lost his precisely enunciated English accent.

On the tapes, Walter describes the failure of the cable from New York to Germany via the Azores; the break was evidently between the Azores and Germany, as he was able to communicate with the Azores station. It's likely that this break was caused by the British cutting of the German cables on 5 August 1914, which was done to force Germany to use insecure radio circuits for its overseas communications. The direct cable connection from New York to Germany was not restored until after the end of the war.

Walter Claypoole died in 1962 at the age of 89 and was buried in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, where he had a cabin, but his memories from over a hundred years ago live on. Below is a transcription of his cable stories from the Far Rockaway and Canso cable stations of the Commercial Cable Company, to which I have added relevant images and background information.

The first few minutes of Walter’s cable story may be heard in this digital transfer from the original tapes (about 2 megabytes, MP3 audio).

Walter Claypoole’s Cable Stories

The next bit of quite good fortune was my introduction to Mr Charles Priest, chief electrician of a leading submarine cable company with many cable lines to Europe. I had a wonderful time with this company, and my stay at Far Rockaway, where the cables came in, was wonderfully interesting and rewarding.

One night I was watching the neat signals coming in on the tape from the German cable. Suddenly the neat wiggles turned into violent splashes of the recording needle. I called the night operator and drew his attention to the fact, suggesting that the cable must have broken. He said immediately, “of course it’s broken, we’ll have to shut down”, which we did. That cut out all traffic on the German cable and it was my good fortune to have the cable, so far as the leg to the Azores was concerned, all to myself for research purposes. It also meant that I could now work during the day at Far Rockaway and cut out all night work.

I should explain perhaps at this point that by now I had acquired a fair competence both in sending messages on the keys and in receiving messages on the slip, though I was by no means expert. My job, now that I had a cable to myself, was to discover by experimental trial and error how best and most easily I could improve the shape of the incoming signals; the squarer and clearer they were, the faster could an operator send messages and read them as they came in. To do this I needed the cooperation of the operator at Fayal in the Azores. He would have to send me messages and when I saw them coming in on the slip I would be able to do something about shaping them up.

Joint Anglo, German and American Cable Station, Fayal, Azores

The German Atlantic cable ran from

Far Rockaway

(Long Island, New York),

to

Fayal

in the Azores, then on to Borkum and Greetsiel in Germany. |

My first order of business was to get acquainted with the operator at Fayal, Azores. I got on the keys and almost immediately received a message from him. We exchanged names and then he informed me that New York had already told him about me and what I wanted him to do at his end. Very clumsily I apologized for my inexperience in both sending and receiving. Back came his reply: “Think nothing of it, old man, I can read you fine. And if I send too fast, just tell me and I’ll slow down.” I took an instant liking to this man, a man I had never seen and probably never would see. Our only means of communication was our ability to translate funny little wiggles down the centre of a receiving tape into words having meaning. These days, of course, these days when radio communication is a commonplace, we would talk over the air; we might even talk over the cable. I do not think there is the same romance about direct communication as there was in those days of the First World War, when we had to rely on our ability to read the tape.

A visitor entering the instrument room of a cable station is at once aware of the cathedral-like stillness that prevails. The only sound is the subdued clicking of the local instruments, which pick off the signals from the tape, amplify them, and send them over land lines to the head office in New York. One event, and one event only, can shatter this almost holy peace and convert it into a sort of mild pandemonium, and that event is the breaking of a cable. As a matter of official routine you’d notify headquarters, but New York is already aware of what has happened, and their experts are already on their way to Far Rockaway.

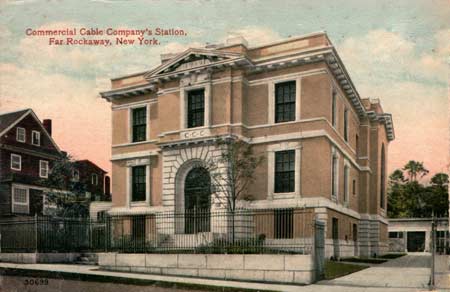

Postcard showing the

cable station of the

Commercial

Cable Company

at

Grandview Avenue,

Far Rockaway,

Long Island, New York. Seven Atlantic cables ran into this office

from the cable

landing at Beach 16th Street.

The New York Times issue of 11 June 1911 reported that "The Lewis H. May Company has resold for Sidney J. Smith a plot of ten lots on the east side of Grandview Avenue, north of the Rue de St. Felix, Far Rockaway, to the Commercial Cable Company, which will erect a receiving station and will remove their present Atlantic cables from Coney Island to the Far Rockaway property."

In 1916 many of the street names in Far Rockaway were changed, and Grandview (sometimes given as Grand View) Avenue was renamed Beach 17th Street/Caffrey Avenue, and Rue de St. Felix was renamed Beach 14th Street/New Haven Avenue. See the map below.

According to the now defunct Rockaway Memories website, the building was sold at the end of the 1930s and converted to a yeshiva, and was eventually demolished in 1985. |

Here is the situation: You know that you have a break in a main cable. What you don’t know is the kind of break nor where the break is. This has to be found out by testing, and this is the next procedure. Meanwhile, at the cable station the operators on duty have been busy in the test room collecting every possible piece of apparatus the experts might require as soon as they arrive. On the table at the left is a map showing the track of the cable from Far Rockaway to its final destination overseas. Depths are marked, and every possible piece of information pertinent to that particular cable has been recorded. The operators have already got the test galvanometer in place and have turned on the projection light. At the exact centre of a long scale directly ahead you will see a spot of light, looking rather like the full moon. The scale is divided in millimeters left and right of the centre, and the movement of this spot is observed by the experts and an effort made to translate what they see into terms of reference to the damage they know has happened. The classic problem of locating a needle in the haystack is child’s play compared with the problem facing the experts of locating a break in a submarine cable, which may be a few miles offshore, or several hundred miles in the depths of the ocean. Curiously enough, before they can even begin to calculate the place where the damage has been done, they must first know the kind of damage. It may be a complete break in the cable, it may be damage to the insulation, it may in very rare cases be a break in the conductor itself. They must know what kind of a break it is before they can start their measurements.

The star marks the general location of the cable landing site, at what is now Beach 16th Street, Far Rockaway. The cable station building was on the north side of Caffrey Ave, east of New Haven Ave. |

|

Finally, after a considerable expenditure of nervous energy and a display of bad temper on the part of all concerned, an agreement is reached and a location for the break in the cable has been decided upon. A cable ship is fitted out and proceeds to the calculated spot. Now the grappling operation starts. The ship steams across the course of the cable and grapples for it at the spot two or three miles on the American side of the calculated place of the break. The dynamometer on board is carefully watched and the cable is brought up. It is then cut and a test made in both directions – one direction will be good, the other will be bad. A new piece of cable is spliced on to the good portion and the cable is then lowered. The ship proceeds eastward and another grapple is made. Again the cable is cut. If they are lucky, the break is now behind them. They splice on to the good part of the cable after sending message both ways. In favourable circumstance they can make the repair inside of a day. In unfavourable circumstances, when storms, for instance, arise, it may take several weeks.

What I have reported here dates back to the early days of World War I, and I am quite sure that techniques and methods have greatly changed since those days.

All of us at the cable station at Far Rockaway took an immense interest in the news coming over the cable from overseas. Traffic was very, very heavy. A great deal of it, of course, was news put onto the cable by the war correspondents, but a very large proportion was personal messages from Americans stranded in Europe who desperately needed help in order to get home to their native land. Some of these messages were extremely pathetic; some were almost humorous; all were intensely interesting. It was our custom to read everything that came over the cable. Most of our operators at Far Rockaway were quite expert in reading the slip. Almost as quickly did they read what was coming over as if it were a printed message in the newspapers. The fascination of it was that it was all raw news. Later it would be edited and printed in the afternoon papers, but here you got the actual stuff, the raw material.

I think you would be interested in hearing about my visit to Nova Scotia, where I was sent to do some work on the cables coming into Canso from London. I travelled by train as far as the port of Mulgrove [actually Mulgrave]. It was a long and tedious train journey and I was glad when it was over. From Mulgrave I had to proceed by a little steamboat across the bay of Chedabucto and the Straits of Canso in order to reach my destination. It was a most interesting trip in reality. We all sat, the passengers that is to say, at the Captain’s table, a very friendly soul, and among the passengers were a newly married couple, a Canadian officer and his bride.

Well, in due course we landed at Canso and I found my way to a little village where the cable station was located, and where I met the Superintendent in charge of the cable station. Let me, if I can, draw a sort of picture of the situation. The little village was entirely devoted to the cable business. The only entertainment was to be found at Canso, and that was a three mile walk along unlighted roads. We all carried little flashlights and did our best to avoid falling into the ditch on either side of the only pathway which was navigable. Everybody who could be spared went into Canso on Saturday night for what entertainment was possible. Usually moving pictures were shown, and they must have been pictures dating back a very long time. I know that I saw newsreels which I had seen two years previously, two years at least.

Commercial Cable Company

Canso

Cable Station

Hazel Hill, Nova Scotia |

Occasionally there was a dance, and it is about one of these dances that I will now say something. At the head of a committee composed of the wives of cable officials was the number one lady of the community, the active, civic-minded, and extremely energetic wife of the Superintendent. This was the first of such dances that had been staged since my arrival, and I had been tipped off as to what my duties would be. I was to dance with every lady on the committee and set a good example for every other man present by being on my feet for every number.

After the Red Cross treasury had benefited from my exertions to the extent of some fourteen shillings or so, a series of incidents occurred which left me somewhat dazed. I had been dancing with the number one lady and was escorting her back to her chair. Suddenly she stopped in her tracks. “Look,” she exclaimed, “they’re here!” I looked in the direction she indicated, and there, to my surprise, was the honeymoon couple: the Canadian officer and his bride. She seized my arm in a strong grip. “Isn’t she adorable” she said excitedly. “I called on her the other day. She’s adorable. Really. She promised to come this evening and bring the Captain, although she explained the poor man does not dance. My boy, you are in luck.” The next moment I was being presented to the couple. I bowed and asked for the honour of a dance. I know only too well my deficiencies as a dancer, but, by some miracle, when I was on the floor dancing with this girl, by some miracle I was a good dancer. A few moments passed, and then I realized, to my embarrassment, that we were alone on the floor; everybody had cleared off – everybody was watching us from the sidelines. Well, there was nothing to do but to go on with the business.

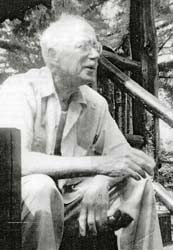

Walter Claypoole in 1947 at his cabin in Boothbay Harbor, Maine |

|

After I had escorted my partner back to her seat by the gallant Captain, I rejoined my hostess and the ladies of the dance committee. They were excited and enthusiastic, and did not delay in telling me the bright idea they had cooked up. Nothing would please them better than my consent to start a dance class in the latest dances, which were so popular in New York. I was lost from the start, and I knew it. When the wife of the Superintendent made up her mind as to a course of action, she ruthlessly followed through to the end. After all, she pointed out, it was my duty in time of war to contribute my bit. If I had such talent in dancing as I had displayed on the floor this evening, it was my duty to impart my talent to others who thirsted for it. The Red Cross would benefit immeasurably from my efforts. Well, in the end of course, I gave in. Classes were started, and I did the best I could, which, I regret to say, was anything but spectacular. What was spectacular, which I learned much later, was the size of the fee my misguided pupils had to hand over to the ladies of the Red Cross committee.

The cable station was under maximum security regulations, and was heavily guarded day and night. Every afternoon the Superintendent went around and whispered the password into the ears of every employee, ready for the next day. You had better remember that password, or you might get into serious trouble. I got into serious trouble one day. I was ordered to halt by the sentry on approaching the cable station, and instead of halting I took a step or two forward to give him the password. Instantly, he sprang at me, with his bayonet practically touching my stomach, and snarled, describing in colourful language what he proposed to do to me if I was so unwise as to make that mistake in the future. My behaviour in the future was beyond reproach, and I never had anything like that happen to me again.

Satellite view of Nova Scotia showing

Mulgrave, Chedabucto Bay, and Canso. |

|