The political and moral influence of the electric telegraph is truly momentous. Not less calculated to excite our astonishment than our admiration at the precision of its agency, the native energy of the human mind is but encouraged by its present attainments to aim at greater discoveries, tending to more important results on the human race.

The difficulty of establishing an electric telegraph under water long prevented any practical attempt being made to continue the communication from the town of Gosport to the Dockyard. An offer was at length made to the Admiralty to lay down a telegraph enclosed in metallic pipes, to be fixed underwater by the aid of diving-bells; but this was subsequently found to be impracticable. The obstacles which then presented themselves have now been fortunately surmounted, and so simple is the apparatus, that it is only necessary to take the telegraphic rope in which the wire was imbedded, and having fastened one end to the shore, the remainder was passed over the stern of a boat as it was rowed across, and it immediately sank to the bottom. The telegraph consists of only one line, and requires no other wires to complete the circuit; the fluid returning to the negative pole through the water to complete the circuit, without the aid of any metallic conductor, except for a short piece of wire thrown over the Dockyard parapet into the water, and connecting it with the batteries. The fact of the water acting as a ready conductor was established beyond all question by the experiments of Mr Snow Harris at this Dockyard. On that occasion the distance travelled by the return circuit through the water was but trifling, compared with the space accomplished in the present instance. The batteries now employed are by Smee; and a very delicate and accurate galvanic detector, invented by Mr Hay, the chemical lecturer at the Dockyard, has been brought into requisition.

Arrival of the Message at the London-Bridge Station |

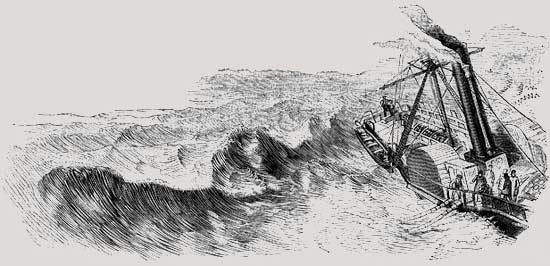

Recent experiments at Folkestone show that it is no Utopian scheme. These were made under the direction of Mr Walker, the superintendent of the South Eastern telegraphs, on board the Princess Clementine, one of the company’s fleet of steamers, in the presence of a large number of scientific gentlemen. It was intended to have taken the wire two miles out to sea, but the wind having risen in the night, the sea was somewhat rough, and it was considered that the steamer would have pitched and rolled so as to endanger the wire, and that it would have been impossible to manage the instrument so as to have kept the needle upright. More than two miles of wire were, however, lowered from her, and submerged in the sea, off the harbour, one end being connected with the telegraphic instrument on the deck of the steamer, and the other end with wires communicating with London. The arrangements having been completed about half-past twelve, messages were sent by Mr Walker to Mr Macgregor, the Chairman of the South Eastern Company, to apprise him that the experiment was entirely successful. This intelligence first passed through the couple of mile of wire “payed out” at sea and in the harbour, and then proceeded to London; and a correspondence was thus maintained between the steam-vessel and the stations of London, Tunbridge and Ashford, which was continued with perfect success at intervals for three or four hours. The bells, also, at the telegraph offices at Tunbridge and London Bridge were vigorously rung by the instrument on board the Princess Clementine, and no greater difficulty was experienced in making the signals with the sub-marine wire than with the ordinary wires on land. In the structure of the wire a suggestion of Mr Walker has been applied to obviate the effects of damp and water often found in tunnels, and it was in this case covered with gutta-percha, making it nearly quarter of an inch in diameter. This wire is to be employed in the Merstham tunnel, and a similar one will be placed in all the tunnels on the line – the Shakspeare [sic], Abbott’s Cliff, and Martello tunnels being already thus provided. The defective insulation of ordinary wires has been the only practical difficulty in the application of the telegraph; and the avoidance of the obstacle is an important advantage. Three or four wires were exhibited on board, one or two of them being probably better adapted for continuous sub-marine communications than that on which the test was made, and among them were specimens of galvanised iron wire, and three-twisted copper wire. The former were thickly coated with gutta percha, some being nearly three-quarters of an inch in diameter. One of them Mr Walker proposes to lay down permanently across Folkestone Harbour, in order to connect the harbour-station with the through communication by the mainland.

The “Message” of the “Clementine” passing

from

the Sea to the Folkestone Station |

The electric power on board was seventy-two plates of the sand battery with weak acidulated water. The experiments of Faraday had already demonstrated that the insulation of wires by gutta percha was complete; and subsequent trials confirm this view. Mr Foster expresses himself so confidently respecting the complete insulation gained by his preparation, that he is willing to find the gutta percha necessary for coating a wire of sufficient length to traverse the Channel whenever the railway directors consent to supply the wire.

It appears however, now to be established, that sub-marine telegraphic communication is practicable, and the extent to which the principle may be carried out within a few years is impossible to conjecture. Such lines, will, of course, be subject to accident, the action of the salt water may affect them; but it appears that with care, prudence, and the application of science, these difficulties may be overcome, and a wonderful international communication be surely and permanently established. What electric eels or other fishes may do with the gutta percha tubes we cannot foresee but vessels rarely anchor in the Channel, there is no drawling [sic] for fish, and, in short, there are very few incidents likely to interfere with this extraordinary operation. Mr Walker also proposes to lay down two or three wires between each port, running in different tracks, and by not making the communication dependent on a single wire, the possibilities of accident would be greatly diminished. In the event, however, of their fracture, the South Eastern Company possess, in their powerful fleet of steamers ready at their command at both ports, great facilities for promptly discovering and fishing up the broken wire, when its repair would be the work of a very short time.

The “Clementine” in a Gale, off the Harbour of Folkestone,

sending an Electric Telegraph Message to the Metropolis

|

Thus do the almost omnipotent powers of time and space seem to have given way before the mighty advance of the empire of mind, and as is advantages are more fully developed and applied, the electric telegraph will, as it were, bring the whole family of man under one roof, and into one room. The metropolis will receive from, and transmit intelligence to, every part of the island. Great Britain will become possessed of a nervous system, whose rapidity and precision is comparable only to that of the human frame; while London will be the sensorium of the acutely sensible and intelligent whole. The most northern or western district will communicate its sensations as the finger or eye transmits its noiseless tiding to the brain. Nor is this all. The attention still directed to the subject by men of science, intelligence, and perseverance, will yet develop many a new dormant principle, which will aid in the advancement of the knowledge and happiness of mankind. The sub-marine telegraph will work a wondrous change. It will unite empires now severed from each other, and which but require the application of present means to bring into connexion and harmonious intercourse. We have long talked on “the family of man” but that which is as yet an intangible abstraction will be practically realised. Termini, a thousand miles apart, with a hundred intermediate stations, will receive, if necessary, the same announcement at the same moment; and the exclamation of a profound electrician – “Give me but an unlimited length of wire, with a small battery, and I will girdle the world with a sentence in a few moments” – will be exemplified, “On a few dials will appear the continued reflex of the world’s history”.