CABOT STRAIT CABLE AND 1857-58 ATLANTIC CABLES

BISHOP JOHN THOMAS MULLOCK

The Roman Catholic Bishop of Newfoundland, J. T. Mullock, as well as carrying out his religious duties, took a great deal of interest in the improvement of communications within Newfoundland, particularly railways and roads. The main method of getting around the island at this time was by sea. On the 8th November 1850 he wrote the following letter to the local newspaper, the St John’s Courier.

To the Editor of The Courier St. John’s, Nov. 8, 1850

I regret to find that in every plan for Transatlantic Communication Halifax is always mentioned and the natural capabilities of Newfoundland entirely overlooked. This has been deeply impressed on my mind by the communications I read in your paper of Saturday last, regarding telegraphic communication between England and Ireland, in which it is said that the nearest telegraphic station on the American side is Halifax, twenty one hundred and fifty five miles from the west of Ireland. Now would it not be well to call the attention of England and America to the extraordinary capabilities of St. John’s as the nearest telegraphic point? It is an Atlantic port, lying, I may say, in the track of the ocean steamers, and by establishing it as the American telegraphic station, news could be communicated to the whole American continent forty eight hours, at least, sooner than by any other route. But how will this be accomplished? Just look at the map of Newfoundland and Cape Breton. From St. John’s to Cape Ray there is no difficulty in establishing a line passing near Holy‑Rood along the neck of land connecting Trinity and Conception Bays, and thence in a direction due west to the Cape. You have then about forty one to forty five miles of sea to St. Paul’s Island, with deep soundings of one hundred fathoms, so that the electric cable will be perfectly safe from icebergs. Thence to Cape North, in Cape Breton, is little more than 12 miles. Thus it is not only practicable to bring America two days nearer to Europe by this route, but should the telegraphic communication between England and Ireland, sixty two miles, be realized, it presents not the least difficulty. Of course we in Newfoundland will have nothing to do with the erection, working, and maintenance of the telegraph; but I suppose our Government will give every facility to the company, either English or American, who will undertake it, as it will be an incalculable advantage to this country. I hope the day is not far distant when St. John’s will be the first link in the electric chain which will unite the Old World and the New.

FREDERIC NEWTON GISBORNE (1824-1892)

Note: Although his first name is sometimes given as Frederick, entries in marriage and death registers, as well as his headstone at Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa, confirm that it was Frederic.

Frederic Newton Gisborne was born in Broughton, Lancashire, on the 8th March 1824, the eldest son of Hartley P. Gisborne. His education, as was common in those days, was provided by the parish priest, who taught him the basics of mathematics and philosophy. In 1845 he emigrated to Canada with his brother. His connection with telegraphy began in 1847 when he obtained employment with the Montreal Telegraph Company and was trained as an operator by Orrin Wood, an associate of Samuel Morse, rising to the position of Chief Operator in the company. In 1847 he became General Manager of the British North American Electrical Association a position he held for two years. It had been set up to encourage the development of a telegraph network throughout Canada. During his tenure he supervised the construction of a line from Quebec City to Rivière du Loup a distance of 112 miles. In 1849 he took up the position of Superintendent of Telegraphs in Nova Scotia and immediately began work on connecting Halifax to America with a line from Halifax to Amherst, New Brunswick, which was already connected to the American telegraph network via a line from Calais, Maine. This gave American newspapers and businesses access to news from Europe much sooner than having to wait for ships to reach Boston or New York.

Stamp issued by Canada in 1987 to commemorate Gisborne’s laying the first ocean cable in North America, connecting Prince Edward Island with New Brunswick in November 1852 |

Gisborne then thought about extending the network to St John’s in Newfoundland. His initial idea was to build a telegraph line from St John’s to Cape Ray and then use carrier pigeons or steamers to carry the news across the Cabot Strait to Cape Breton Island where it could be transmitted throughout North America. This was of course dependent on persuading trans Atlantic steamers to call at St John’s. It was on the basis of this scheme that Gisborne sent his petition to the Newfoundland Legislature. In it he undertook to carry out a survey and then construct a line from St. John’s to Cape Ray subject to the company being granted exclusive rights to operate the telegraph service in Newfoundland. Gisborne visited Newfoundland in 1851 to present his case and he was granted the necessary permission and awarded £500 to carry out a survey.

Having succeeded Gisborne then requested permission to build a line from St. John’s to Carbonear and was again successful. He set up the St. John’s-Carbonear Telegraph Company and work began on the line in September 1851. He also requested permission to erect a line from St John’s to Trepassey and Cape Race. His idea with this was that if the steamers decided not to call at St. John’s they could drop off barrels containing news from Europe, at Cape Race, where a boat would recover them and sail back to Trepassey where the information could be sent over the telegraph to Cape Ray and across the Cabot Strait by pigeon. Following the failure of the 1858 cable a boat was chartered to recover “Barrel Mail” dropped overboard from trans Atlantic steamers, off Cape Race, the scheme lasting until the landing of the 1866 cable.

When the Carbonear line reached Brigus, Gisborne set off to survey the line to Cape Ray. In all it took four months under extremely difficult conditions. He then made his way to New York to raise capital for the line. While there he heard of the Brett brothers cable laying expedition across the English Channel. He then revised his plans and considered the idea of laying a cable across the Cabot Strait via St Paul’s Island. He contacted the Nova Scotia government for permission to land a cable on Cape Breton Island. This was refused. Undaunted he then went for a cable across to Prince Edward Island with a shorter one across the Northumberland Strait to New Brunswick.

In 1852 he travelled to England and met the Brett brothers and after consulting them purchased 15 nm of cable from R. S. Newall & Company for the Northumberland Strait crossing. The cable was laid in November 1852. It worked for less than a year.

Having received the go ahead from the Newfoundland government for the Cape Ray line and the one to Cape Race along with a 30 year monopoly and having found backers the Newfoundland Electric Telegraph Company was set up and work on the line began in 1853. Only forty miles of line had been constructed when Gisborne’s backers pulled out leaving him with all the outstanding debts. Returning to New York in the hope of finding new backers he met Matthew Field, and was invited to put his ideas to his brother, Cyrus Field.

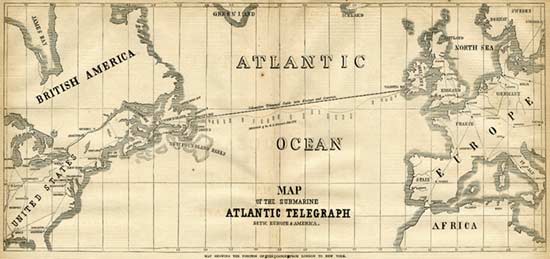

NEW YORK, NEWFOUNDLAND AND LONDON TELEGRAPH COMPANY

Field listened to Gisborne’s ideas and spent some time thinking about them. He checked the position of St. John’s on the globe in his study and found that it was 1,000 miles nearer to Ireland than New York. A new idea came to him. Why stop at St. John’s? Why not continue to Ireland. The potential rewards of such a scheme would be enormous. His knowledge of telegraphy was nil so he wrote to Samuel Morse for advice. Morse told him the project was feasible. Morse was later appointed Scientific Advisor to the company. Field also wrote to Lieutenant Matthew Maury, who was head of the newly formed United States Naval Observatory, Washington. At the time of receiving Field’s letter he had been working on the results of a survey of winds and currents in the Atlantic carried out by Lt. Berryman aboard the USS Dolphin in the summer of 1853, who while carrying out the survey had also taken a series of soundings at intervals of 30 miles.

Maury’s reply was equally positive. He wrote:-

This line of deep‑sea soundings seems to he decisive of the question of the practicability of a submarine telegraph between the two continents, in so far as the bottom of the deep sea is concerned. From Newfoundland to Ireland, the distance between the nearest points is about sixteen hundred miles; and the bottom of the sea between the two places is a plateau, which seems to have been placed there especially for the purpose of holding the wires of a submarine telegraph, and of keeping them out of harm’s way. It is neither too deep nor too shallow; yet it is so deep that the wires but once landed, will remain for ever beyond the reach of vessels’ anchors, icebergs, and drifts of any kind, and so shallow, that the wires may be readily lodged upon the bottom.

The depth of this plateau is quite regular, gradually increasing from the shores of Newfoundland to the depth of from fifteen hundred to two thousand fathoms, as you approach the other side....

I [do not] pretend to consider the question as to the possibility of finding a time calm enough, the sea smooth enough, a wire long enough, a ship big enough, to lay a coil of wire sixteen hundred miles in length; though I have no fear but that the enterprise and ingenuity of the age, whenever called on with these problems, will be ready with a satisfactory and practical solution of them.

I simply address myself at this time to the question in so far as the bottom of the sea is concerned, and so far as that the greatest practical difficulties will, I apprehend, be found after reaching soundings at either end of the line, and not in the deep sea.... Therefore, so far as the bottom of the deep sea between Newfoundland, or the North Cape, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, and Ireland, is concerned, the practicability of a Submarine Telegraph across the Atlantic is proved.

Profile of the bottom of the Atlantic between Valentia Bay and St Johns

Newfoundland as sounded by the U.S. Steamer “Arctic”: Capt. O.H. Berryman

Illustrated London News, 6 December 1856 |

|

|

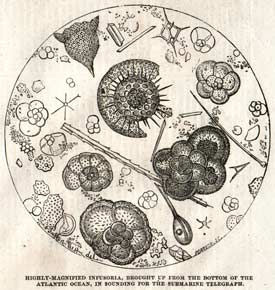

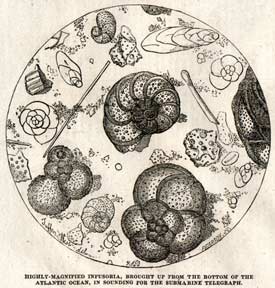

Highly-magnified infusoria, brought up from the bottom of

the

Atlantic Ocean, in sounding for the submarine telegraph

Illustrated London News, 6 December 1856 |

Commander Joseph Dayman of the Royal Navy in HMS Cyclops also carried out a series of soundings soon afterwards, these were taken every 20 miles, which confirmed Maury’s conclusions.

Field approached four others, Peter Cooper, Moses Taylor, Marshall O. Roberts and Chandler White, to help finance the first stage, that of building the Newfoundland landline and with the necessary permission getting a cable laid between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, then building another landline across Cape Breton Island. The first meeting took place on the 7th March when Field arranged for everyone to meet Gisborne. This meeting took place at the Clarendon Hotel on Broadway and Thirty Eighth Street. The next three meetings were held at Field’s house. They set up the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company with a capital of $1.5 million on the 10th March 1854 and then approached the Newfoundland government about purchasing the assets of Newfoundland Electric Telegraph Company. They stated that subject to a successful agreement they would settle the bankrupt company’s debts. The new company was allowed to take over the Newfoundland Electric, it was granted a 50 year monopoly on landing cables in Newfoundland and Labrador, a guarantee of interest on $250,000 of company bonds and a grant of 50 square miles of land, all conditional on the landline and the cable to Cape Breton Island being successfully completed. A further 50 square miles of land would be given on the successful completion of the cable between Ireland and Newfoundland. Similar discussions took place with the governments of Prince Edward Island, which granted a 50 year monopoly on landing cables, 1,000 acres of land and $1500 a year in currency. Nova Scotia and the State of Maine both granted a 50 year monopoly of cable landing rights. Also in Nova Scotia the rights to build and operate a line 140 miles long across Cape Breton Island to connect with the existing telegraph network.

Peter Cooper’s factory at Trenton, New Jersey, undertook to supply the telegraph wire for the landlines. Matthew Field was appointed Supervising Engineer for the Newfoundland landline with Chandler White being responsible for the administrative side of the business. David Field was named as the company lawyer.

Gisborne’s final involvement in the scheme was as Consulting Engineer for the landline, he then disappears from the story. However the people of St. John’s showed their appreciation in the following way.

Testimonial to Mr. F. N. Gisborne as reported in a Manchester Newspaper:

A very beautiful, valuable, and appropriate piece of plate has been prepared as a testimonial to Mr. Frederick Newton Gisborne, eldest son of Hartley P. Gisborne Esq., of this city, contributed and to be presented by the inhabitants of St. John’s, Newfoundland, as marking their sense of the energy and perseverance he has displayed in traversing the previously unexplored parts of the island in anticipation of the introduction of the electric telegraph. The design is bold, and highly characteristic of the subject portrayed. At the summit of a rocky eminence, in frosted silver, stands a figure of science, with a wreath of immortelles in her upraised and extended left hand, ready to crown the deserving enterprise a figure of Roman character, with a hatchet in one hand, evincing vigour and determination, and in the other a pair of compasses, indicative of skill and calculation has struggled nearly to the highest point, and is handing the compasses to science. The rocky heights are studded here and there with North American fir trees. Upon the front of the base an oval is formed by a cable and within the coil is the inscription; on the opposite side is represented a vessel at sea laying down the cable for the electric telegraph. A group of seals and a group of beavers occupy part of the space between these. There is also engraved representations of American scenery, with Indian wigwams. The specific character of the testimonial is further indicated by the whole being encircled by telegraph posts and wires. Manchester may justly take some credit to itself on account of its relation to the gentleman whose enterprise this testimonial commemorates.

Forty miles of line had been erected by Gisborne before he was forced to abandon the scheme. The remainder was split into sections each having its own construction crew, requiring a total workforce of 600 men. As the working parties could only be supplied by sea the steamer Victoria was purchased to carry out this task. Work began in late Spring 1854 and it was expected to be completed within a few months. With all this set in motion Cyrus Field made the first of over fifty trans Atlantic trips in connection with the whole plan.

On his return from England in March 1855 Cyrus Field contacted his brother, Matthew, asking him how long it would be before he completed the line. The reply was not encouraging: possibly 1855, but more likely 1856. In fact the line was not completed until October 1856. The total cost of the landline amounted to $500,000, one third of the company’s capital.

Keeping the completed landline working was proving to be as big a problem as building it. By December 1856 it was out of action and no one had any idea of how to get it working again. Cyrus Field appealed to business associates for suggestions and he was advised to recruit Alexander McLennan Mackay, who though only 26 years of age, was Superintendent of the Nova Scotia Telegraph Company. Field persuaded him to join Newfoundland Telegraph. He arrived in Newfoundland in 1857 and with a work crew walked the whole line from Cape Ray to St. John’s carrying out repairs and in some instances rebuilding the line, which cost a further $100,000. To get the system completed as far as St. John’s had cost the company $1,000,000.

THE CABOT STRAIT CABLE

On his arrival in England Cyrus Field met up with John Brett and on his advice placed an order with Kuper and Co to supply 85 nm of cable, to be laid between Cape Ray, Newfoundland and Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. The cable was similar to that used for the 1851 Cross Channel Cable.

The core for the cable was supplied by the Gutta Percha Company to Kuper & Company, but by the time the cable was manufactured Richard Atwood Glass had bought out Kuper and was joined by George Elliot and the firm was renamed Glass, Elliot & Company. The core consisted of 4 copper wires of No 16 BWG each individually coated with two layers of gutta percha to No 2 BWG, these were then twisted together and the spaces between packed with tarred hemp, the whole being covered in another layer of gutta percha and then wrapped in tarred hemp followed by 12 No 9 BWG armouring wires. On completion it was loaded aboard the barque Sarah L. Bryant which was to transport the cable to Newfoundland and would also lay the cable.

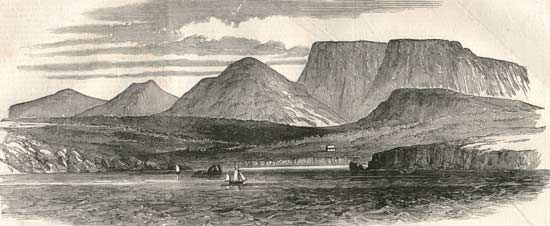

Terminus at Cape Ray, Newfoundland

Illustrated London News, 20 October 1855 |

Initially the cable was to be landed at Cape Ray, but ice was known to accumulate there and Port au Basques was suggested as an alternative. In the end it was decided to land the shore end in a cove just east of Cape Ray. The Cape Breton Island shore end was to be brought ashore in a bay to the east of Cape North. If there was insufficient cable to reach this place it was to be landed at Cape North Point and then later extended to the actual landing site. Should problems occur before this the cable would be terminated on St. Paul’s Island and a cable laid from there to Cape North in the following year.

So sure was he of success Cyrus Field invited journalists, scientists and friends who along with the directors of the company and their families left New York on 7 August 1855 on board the steamer James Adger. Chartered at a rate of $750 a day and with Captain S. C. Turner in charge, ths ship headed for Port au Basques, where the Sarah L. Bryant with Captain Pousland in charge should have been waiting, along with the company steamer Victoria. She was not there and so they sailed on to St. John’s hoping to meet up with her there. It was a few days before she arrived looking somewhat the worse for wear having encountered bad weather on her way out from England. Repairs were carried out and the cable machinery assembled and the two vessels made for Cape Ray.

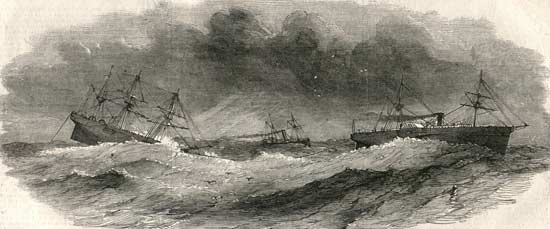

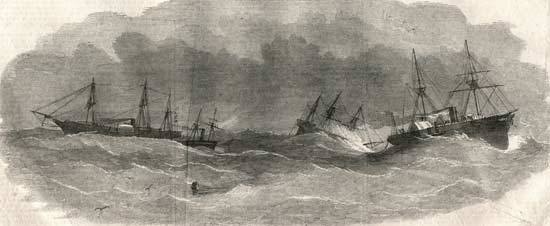

Sarah L. Bryant Victoria James Adger |

The expedition finally got under way on Wednesday 22 August 1855 with the Sarah Bryant being towed to Cape Ray Cove. Problems arose landing the shore end because of the heavy swell and dense fog and it was not until the Thursday night that the task was completed. Friday was spent waiting for the fog to lift. On the morning of Saturday 25 August with a strong north westerly wind blowing James Adger attempted to get a tow aboard the Sarah L. Bryant and after three attempts finally succeeded and laying began at a speed of just over a mile an hour. Due to the slow speed, and the strong wind James Adger had trouble in keeping station and eventually the two ships collided and the tow had to be cut the James Adger sailed clear and anchored. The Sarah L. Bryant with the cable still intact found herself drifting rapidly towards rocks on the shore. She hoisted distress signals and the little steamer Victoria went to her aid but was unable to tow her clear. Captain Pousland after cutting the cable succeeded in getting a small amount of sail set and Captain Turner managed to get a tow aboard and was able to pull her clear. Fortunately all that was lost was two miles of cable.

Sarah L. Bryant Victoria (alongside) James Adger

Detail from a painting by John Wells Stancliff of the 1855 expedition

(Private Collection)

Research shows that J.W. Stancliff was not on board any of the ships of the cable expedition in 1855, and while it was a scene he always wanted to paint, he did not do it until 1878.

If any site visitor has further information on Stancliff’s life or work, please email me. |

By Sunday the wind had abated and the sea was calm, the end of the cable was recovered and spliced to that aboard the Sarah L. Bryant and with Victoria towing her out to deeper water laying commenced once again. But before James Adger could take over the tow the cable parted at the splice made that morning. It was decided to abandon this section of cable and lay a new shore end and this was carried out on the Monday and Victoria then towed Sarah L. Bryant into deeper water ready to start laying the following day.

Early on Tuesday morning laying commenced at the rate of about 1½ nm an hour with frequent stops to get rid of kinks in the cable as it came up from below deck. Testing was carried out between ship and shore and during the morning it was found that one of the four conductors had failed. Around midnight on the Tuesday a break occurred aboard ship and repairing it took until 7.00 am the next morning. Noon Wednesday 29 August a second conductor failed and during the day the wind and sea got up. Another break occurred on board ship and by the time this was repaired

the pitching and tossing had strained the cable so badly that a third conductor had failed. By now the weather was so bad, the wind having reached near hurricane force, that the ship was in danger of foundering, it was decided to cut the cable and abandon the expedition. As the cable was cut HMS Argus arrived to offer assistance if required and remained with the other vessels until the weather improved.

Argus Victoria Sarah L. Bryant James Adger |

The following morning the weather had eased and those on board the Sarah L. Bryant, the cable crew and Cyrus Field’s guests managed to return to the James Adger. Both vessels then set out for Sydney, Nova Scotia, where stores were replenished and the Sarah L. Bryant was made ready for her return to England. The remaining cable was offloaded. The James Adger left Sydney on Sunday 2 September and arrived in New York just over three days later. The total cost of hiring the vessel came to $21,750.

After the failure of this cable Field set out once again for England to order a new cable, this time he arranged for Glass, Elliot & Company to manufacture and lay the cable. The new 85 nm cable consisted of seven copper wires No 22 BWG, six strands being wrapped around the seventh, covered with two layers of gutta percha to No 1 BWG and 12 iron wires No 9 BWG was used for the armouring. The cable was successfully laid in the summer of 1856 by the steamer Propontis. The same vessel was used to lay a similar 12 nm long cable between Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick to replace the one laid by Gisborne which had failed within a year of being installed.

THE ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH COMPANY

Having succeeded in completing the line to St. John’s, thoughts now turned to laying a cable from Ireland to Newfoundland. In July 1856 armed with his 50 year monopoly and land grants from the Newfoundland Government he sailed for England. On arrival he met with Charles Bright and John Watkins Brett both of whom had been working towards the laying of an Atlantic cable. On the 26th September 1856 the three reached agreement on the setting up of a company to lay a cable from Ireland to Newfoundland. The three signed the following statement:

Mutually, and on equal terms we engage to exert ourselves for the purpose of forming a Company for establishing and working of electric telegraphic communication between Newfoundland and Ireland, such Company to be called the Atlantic Telegraph Company, or by such other name as the parties hereto shall jointly agree upon.

The Atlantic Telegraph Company was registered on the 20th October 1856 with a capital of £350,000 in the form of 350 shares of £1,000. A meeting took place on the 12th November 1856 at the Underwriters Rooms at the Liverpool Exchange, where the shares were offered for sale. Similar meetings were held at the Magnetic Telegraph Offices in Glasgow and Manchester and within a few days all shares had been sold. Most of them were taken up by the directors of the Magnetic Telegraph Company, which owned the lines in Ireland over which messages from the USA would travel to England. Cyrus Field reserved 75 shares for American businessmen, but he had great difficulty in persuading anyone to invest. Only 27 of the shares were sold and Field had to put up the money for the remainder. The first official meeting of the company was held on the 12th November 1856 at which the board was elected.

GOVERNMENT SUBSIDY

Following the success of the share sale, the British Government was approached for assistance with ships and a subsidy. Negotiations were successful as shown in the following letter received by the company.

TREASURY CHAMBERS,

November 10th, 1856.

SIR,‑

Having laid before the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury your letter of the 15th ult., addressed to the Earl of Clarendon, requesting certain privileges and protection in regard to the line of telegraph which it is proposed to establish between Newfoundland and Ireland, I am directed by their Lordships to inform you that they are prepared to enter into a contract, based upon the following conditions, viz:‑

1. It is understood that the capital required to lay down the line will be (£350,000) three hundred and fifty thousand pounds.

2. Her Majesty’s Government engage to furnish the aid of ships to take what soundings may still be considered needful, or to verify those already taken, and favourably to consider any request that may be made to furnish aid by their vessels in laying down the cable.

3. The British Government, from the time of the connection of the line, and so long as it shall continue in working order, undertakes to pay at the rate of (£14,000) fourteen thousand pounds a year, being at the rate of four per cent. on the assumed capital, as a fixed remuneration for the work done on behalf of the Government, in the conveyance outward and homeward of their messages. This payment to continue until the net profits of the proposed Company are equal to a dividend of six pounds per cent. per annum, when the payment shall be reduced to (£10,000) ten thousand pounds a year, for a period of twenty‑five years.

It is, however, understood that if the Government messages in any year shall, at the usual tariff charged to the public, amount to a larger sum, such additional payment shall be made as equivalent thereto.

4. That the British Government shall have a priority in the conveyance of their messages over all others, subject to the exception only of the Government of the United States, in the event of their entering into an arrangement with the Telegraph Company similar in principle to that of the British Government, in which case the messages of the two Governments shall have priority in the order in which they arrive at the stations.

5. That the tariff of charges shall be fixed with the consent of the Treasury, and shall not be increased, without such consent being obtained, as long as this contract lasts.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

JAMES WILSON.

On receiving this letter the company then began negotiations with the United States Government and were successful in receiving the same concessions.

THE CABLE

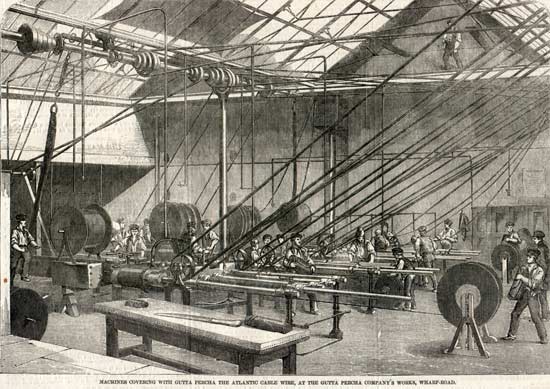

Machines covering with gutta percha the Atlantic Cable wire,

at the Gutta Percha Company’s works, Wharf Road |

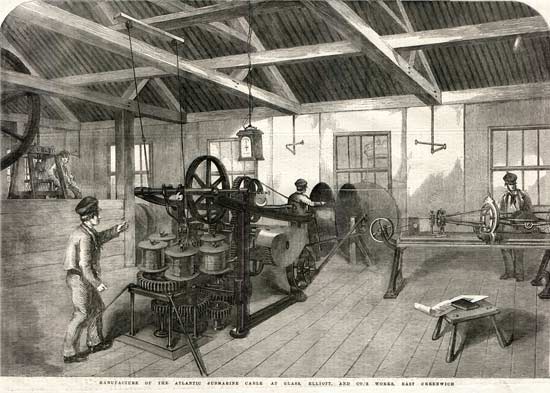

The Gutta Percha Company was awarded the contract for manufacturing the insulated core and the contract for the armouring was split equally between Glass, Elliot & Co and R. S. Newall & Co. The cable consisted of 7 strands of No 22 BWG copper wire, six of these being wrapped around the seventh, it was then covered with three layers of gutta percha to No 4 BWG. This core was then wrapped in jute yarn which had been soaked in a composition consisting of 5/12 Stockholm tar, 5/12 pitch, 1/12 boiled linseed oil and 1/12 common bees wax. The armouring consisted of 18 strands each strand composed of 7 of the best charcoal iron wires each of No 22 BWG, six being wrapped around the seventh,. The completed cable as it left the machine was coated with a composition which was made up of 3 barrels of tar, half a barrel of pitch, 12 lbs of beeswax and 6 gallons of linseed oil per mixing. Twelve to thirteen gallons of this mixture was used per nm. In all 2,500 nm of cable was ordered.

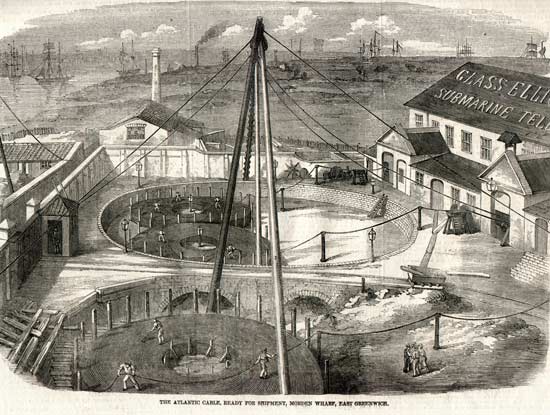

Manufacture of the Atlantic Submarine Cable

at

Glass, Elliott, and Co’s works, East Greenwich |

The Atlantic Cable ready for shipment, Morden Wharf, East Greenwich |

Bright had requested the copper conductor be of 392 lbs per nm but the contract, specifying a conductor of 107 lbs per nm, had already been signed by the time of his appointment as Chief Engineer

THE 1857 CABLE EXPEDITION

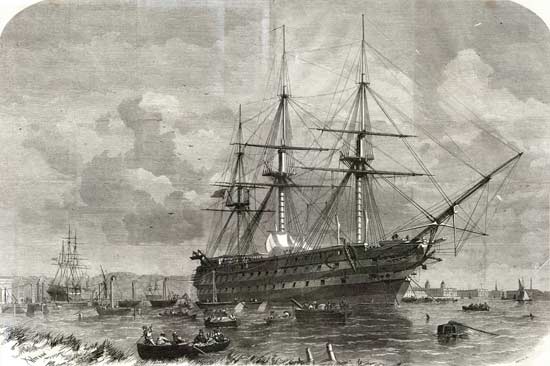

The British Government supplied HMS Agamemnon as cable layer with HMS Leopard to assist and HMS Cyclops, a small vessel used for taking soundings and leading the fleet. The United States Government provided USS Niagara as cable layer with USS Susquehanna to assist. HMS Agamemnon took on board the cable armoured by Glass, Elliot and Company, while USS Niagara travelled to the Mersey to load the cable armoured by R.S. Newall & Co.

H.M.S. Agamemnon, 91 Guns. Shipping the English Portion of

the Atlantic Submarine Cable at East Greenwich

Illustrated London News, 1 August 1857 |

Edward Orange Wildman Whitehouse was appointed Chief Electrician by the Board, but due to ill health didn’t travel on the expedition. Those electricians who did travel were:- C.V. Sauty, J.C. Laws, F. Lambert, H.A.C. Saunders, Benjamin Smith, Richard Collett and Charles Gerhardi. They were split into two parties one for each ship. On the mechanical side were the following:- Samuel Canning, William Henry Woodhouse, F.C. Webb and Henry Clifford. These four along with Bright travelled on the Niagara as did C.V. Sauty and J.C. Laws. Samuel Morse was also on board the Niagara, but suffered badly from sea sickness and played little part in the proceedings. Professor Thomson and Navigating Master H.A. Moriarty, loaned by the Admiralty, travelled on the Agamemnon.

The method of taking the Atlantic Telegraph cable on board -

sketched from the stern gallery of Her Majesty’s Ship “Agamemnon” |

Stereoview of Agamemnon loading cable.

Undated, but the caption is identical to that of the ILN 1857 woodcut above

Her Majesty’s Ship

"AGAMEMNON"

91 Guns. Shipping the English portion of

the Atlantic Sub-Marine Cable,

At East Greenwich |

Detail of ship and caption

Stereoview images courtesy of and copyright © 2012

Ray Norman, World of Stereoviews |

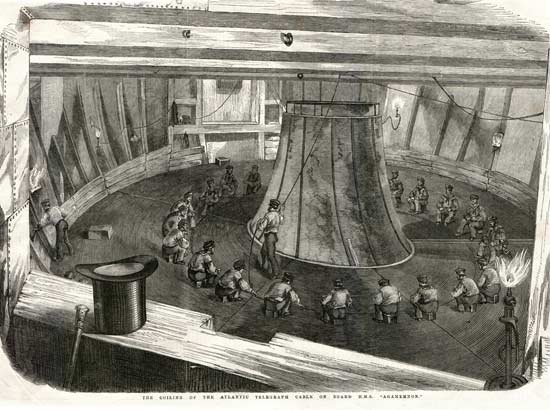

The coiling of the Atlantic Telegraph cable on board HMS “Agamemnon” |

Having completed loading, the two ships set out for Queenstown, Ireland, arriving on the 30th July 1857. They anchored about three quarters of a mile apart and a piece of cable was passed between the two enabling the whole 2,500 nm of able to be tested. These tests conducted by Mr. Whitehouse went on for two days. On the 3rd August the two ships with their escorts and two small vessels, the steam tug Willing Mind and HM Tender Advice who were to undertake the laying of the shore end set out for Valentia arriving there the following day.

On the morning of the 5th August Bright spent the morning making arrangements for landing the shore end, the site being a small cove known as Ballycarberry in Valentia Harbour. The operation to land the cable began at about 2 o’clock that afternoon.

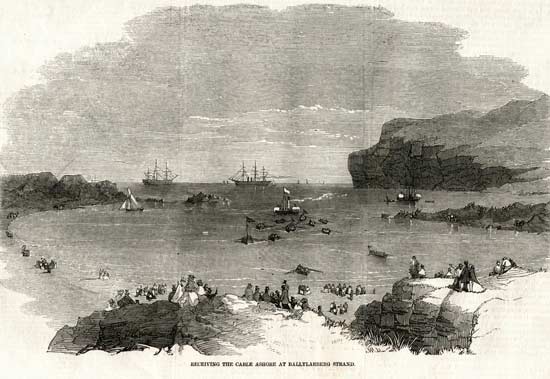

Receiving the cable ashore at Ballycarberry Strand |

A newspaper report of the event:

Valentia Bay was studded with innumerable small craft decked with the gayest bunting. Small boats flitted hither and thither, their occupants cheering enthusiastically as the work successfully progressed. The cable boats were managed by the sailors of the Niagara and the Susquehanna. It was a well designed compliment, and indicative of the future fraternisation of the nations, that the shore rope was arranged to be presented at this side of the Atlantic to the representative of the Queen by the officers and men of the United States Navy, and that at the other side the British officers and sailors should make a similar presentation to the President of the great Republic.

From the mainland the operations were watched with intense interest. For several hours the Lord Lieutenant stood on the beach surrounded by his staff and the directors of the railway and telegraph companies, waiting the arrival of the cable. When at length the American sailors jumped through the surge with the hawser to which it was attached, his Excellency was among the first to lay hold of it and pull it lustily to the shore. Indeed, every one present seemed desirous of having a hand in the great work. Never before, perhaps, were there so many willing assistants at the long pull, the strong pull, and the pull all together.

At half ‑past seven o’clock the cable was hauled on shore at Ballycarberry Strand, and formal presentation was made of it to the Lord Lieutenant, his Excellency expressing a hope that the work so well begun would be carried to a satisfactory completion.

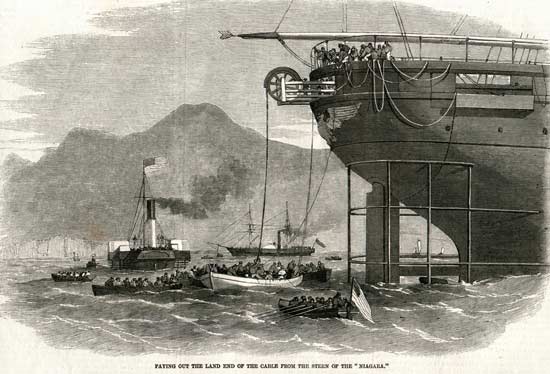

Paying out the land end of the cable from the stern of the “Niagara” |

Bright’s report to the Directors gives full details of the expedition:

REPORT TO THE DIRECTORS OF THE ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH COMPANY, AUGUST 1857.

After leaving Valentia on the evening of the 7th inst., paying out of the cable from the Niagara progressed satisfactorily until immediately before the mishap.

At the junction between the shore and the smaller cable about eight miles from the starting point, it was necessary to stop to renew the splice. This was successfully effected, and the end of the heavier cable lowered by a hawser until it reached the bottom, two buoys being attached at a short distance apart to mark the place of union.

By noon of the 8th we had paid out forty miles of cable, including the heavy shore end. Our exact position at the time was in lat. 50° 59' 36" N., long. 11° 19' 1" W., and the depth of the water according to the soundings taken by the Cyclops whose course we nearly followed - ninety fathoms. Up to 4 p. m. on that day the egress of the cable had been regulated by the power necessary keep the machinery in motion at a slightly higher rate than that of the ship; but as the water deepened it was necessary to place some further restraint upon the cable by applying pressure to the friction drums in connection with the paying‑out sheaves. By midnight eighty‑five miles had been safely laid, the depth of the water being then a little more than 200 fathoms.

At eight o’clock on the morning of the ninth we had exhausted the deck coil in the after part of the ship having paid out 120 miles. The change to the coil between decks forward was safely made. By noon we had laid 136 miles of cable, the Niagara having reached lat. 52° 11' 40" N., long. 13° 0' 20" W., and the depth of the water having increased to 410 fathoms. In the evening the speed of the vessel was raised to five knots. I had previously kept down the rate at from three to four knots for the small cable, and two for the heavy end next the shore, wishing to get the men and machinery well at work prior to attaining the speed which I had intended making. By midnight 189 miles of cable had been laid.

At four o’clock in the morning of the 10th the depth began to increase rapidly from 550 to 1750 fathoms in a distance of eight miles. Up to this time a strain of 7 cwt. sufficed to keep the rate of the cable near enough to that of the ship; but as the water deepened the proportionate speed of the cable advanced, and it was necessary to augment the pressure by degrees until at a depth of 1700 fathoms the indicator showed a strain of 15 cwt., while

the cable and the ship were running five and a half and five knots respectively.

At noon on the 10th we had paid out 255 miles of cable the vessel having made 214 miles from the shore being then in lat. 52° 27' 50" N., long. 16° 15' W., At this time we experienced an increasing swell, followed later in the day by a strong breeze.

From this period having reached 2000 fathoms water, it was necessary to increase the strain by a ton by which the rate of the cable was maintained in due proportion to that of the ship. At six o’clock in the evening some difficulty arose through the cable getting out of sheaves of the paying out machine, owing to the pitch and tar hardening in the groove, and a splice of large dimensions passing over them. This was rectified by fixing additional guards and softening the tar with oil. It was necessary to bring up the ship, holding the cable by stoppers until it was again properly disposed around the pulleys. Some importance is due to this event, as showing that it is possible to ‘lay to’ in deep water without continuing to pay out the cable, a point upon which doubts have frequently been expressed.

Shortly after this the speed of the cable gained considerably on that of the ship, and up to nine o’clock, while the rate of the latter was about three knots, by the log, the cable was running out from five and a half to five and three quarter knots.

The strain was then raised to 25 cwt., but the wind and the sea increasing, and a current at the same time carrying the cable at an angle from the direct line of the ship’s course, it was found insufficient to check the cable, which was at midnight making two and a half knots above the speed of the, ship, and sometimes imperilling the safe uncoiling in the hold.

The retarding force was therefore increased at two o’clock to an amount equivalent to 30 cwt., and then again in consequence of the speed continuing to be more than it would be prudent to permit to 35 cwt; by this, the rate of the cable was brought to a little short of five knots, at which it continued steadily until 3.45, when it parted, the length paid out at the time being 380 miles.

In proceeding to the fore part of the ship I heard the machine stop. I immediately called out to relieve the brakes, but when I reached the spot the cable was broken. On examining the machine—which was otherwise in perfect order—I found that the brakes had not been released, and to this, or to the hand wheel of the brake being turned the wrong way, may be attributed the stoppage and consequent fracture of the cable.

When the rate of the wheels grew slower as the ship dropped her stern in the swell, the brake should have been eased. This had been done regularly when ever an unusually sudden descent of the ship temporarily withdrew the pressure from the cable in the sea. But owing to our entering the deep water the previous morning, and having all hands ready for any emergency that might occur there, the chief part of my staff had been compelled to give in at night through sheer exhaustion, and hence, being short-handed, I was obliged for the time to leave the machine without, as it proved, sufficient intelligence to control it.

I perceive that on the next occasion it will be needful, front the wearing and anxious nature of the work, to have three separate relays of staff, and to employ for attention to the brakes, a higher degree of mechanical skill.

The origin of the accident was, no doubt, the amount of retarding strain put upon the cable, but had the machine been properly manipulated at the time, it could not possibly have taken place.

For three days in shallow and deep water, as well as in rapid transitions from one to the other, nothing could be more perfect than the working of the cable machinery. It had been made extra heavy with a view to recovery work. It, however, performed its duty so smoothly and efficiently in the smaller depths—where the weight of the cable had less ability to overcome its friction and resistance—that it can scarcely be said to be too heavy for paying out in deep water, where it was necessary, from the increased weight of cable, to restrain its rapid motion, by applying to it a considerable degree of additional friction. Its action was most complete, and all parts worked well together.

I see how the gear can be improved by a modification in the form of sheave, by an addition to the arrangement for adjusting the brakes and some other alterations; but with proper management, without any change whatever, I am confident that the whole length of cable might have been safely laid by it. And it must be remembered, as a test of the work which it has done, that unfortunate as this termination to the expedition is, the longest length of cable ever laid has been payed out by it, and that in the deepest water yet passed over.

After the accident had occurred, soundings were taken by Lieutenant Dayman from the Cyclops, and the depth found to be 2000 fathoms.

It will be remembered that some importance was attached to the cable on board the Niagara and Agamemnon being manufactured in opposite lays. I thought this a favourable opportunity to show that practically the difference was not of consequence in effecting the junction in mid‑ocean. We therefore made a splice between the two vessels. This was then lowered in a heavy sea, after which several miles were paid out without difficulty.

I requested the commanders of the several vessels to proceed to Plymouth, as the docks there afford better facilities than any other port for landing the cable should it be necessary to do so.

The whole of the cable remaining on board has been carefully tested and inspected, and found to be in as perfect condition as when it left the works at Greenwich and Birkenhead respectively.*

One important point presses for your consideration at an early period. A large portion of cable already laid may be recovered at a comparatively small expense. I append an estimate of the cost, and shall be glad to receive your authority to proceed with this work.

I do not perceive in our present position any reason for discouragement; but I have, on the contrary, a greater confidence than ever in the undertaking.

It has been proved beyond a doubt that no obstacle exists to prevent our ultimate success; and I see clearly how every difficulty which has presented itself in this voyage can be effectually dealt with in the next.

The cable has been laid at the expected rate in the great depths; its electric working through the entire length has been satisfactorily accomplished, while the portion laid, actually improved in efficiency by being submerged—from the low temperature of the water and the increased close texture of gutta‑percha thereby effected.

Mechanically speaking, the structure of the cable has answered every expectation that I had formed of it. Its weight in water is so adjusted to the depth that strain is within a manageable scope; while the effects of the undercurrents upon its surface prove how dangerous it would be to lay a much lighter rope, which would, by the greater time occupied in sinking, expose an increased surface to their power, besides its descent being at an angle such as would not provide for good laying at the bottom.

On the other hand, in regard to any further length made, I would take this opportunity of again strongly urging the desirability of a much larger conductor and corresponding increase in the weight of insulation, in accordance with my original recommendation.

I have the honour to remain, gentlemen, yours very faithfully.

CHARLES T. BRIGHT.

Engineer‑in‑Chief.

To the Directors of the Atlantic Telegraph Company.

The squadron sailed to Keyham (now Devonport), Plymouth to unload the remaining cable, they then returned to their normal duties.

*Bright's assurance to the company that the remaining cable from the 1857 expedition was in good condition was based on an examination of the cable by Henry Clifford and John Kell. They reported their findings to Bright in a letter dated August 17th 1857:

U.S.Frigate Niagara Augst. 17th 1857

C.T. Bright Esq.

Engineer to the Atlantic Telegraph Compy.

Sir

We have been requested by Capt. Hudson to attend on board the Niagara this morning for the purpose of examining the present state of the Telegraph Cable.

We hereby declare that to the best of our judgement the cable is perfectly good and not injured at the present time by the salt water that had been thrown on the coils to keep them cool.

We are Sir

Yours most Obtly.

John Kell

Henry Clifford

|

While the cable may have been in good condition at the conclusion of the 1857 expedition, its storage at Plymouth into the summer of 1858 left it much less so. Some of this cable was used on the second expedition of 1858, and the compromised condition of its insulation almost certainly contributed to the failure of the cable after a few weeks of operation.

THE FIRST 1858 CABLE EXPEDITION

Work began immediately to manufacture enough cable to replace that lost (in all a further 700 nm was produced, giving a total of 3000 nm.) and to raise sufficient money to mount another expedition. This took quite some time but eventually sufficient capital was raised. Other work included the redesigning of the cable paying out gear to eliminate a similar problem as occurred on the 1857 expedition. Probably the most important piece of equipment to be produced was Professor Thomson’s Mirror Galvanometer, which reflected a beam of light onto a scale indicating whether a negative or positive pulse had been transmitted.

Charles Bright decided to have a trial of all laying operations before the actual expedition started and so HMS Agamemnon, USS Niagara along with the Royal Navy vessels, Gorgon, Valorous and Porcupine set out for the Bay of Biscay.

The following is an extract from the engineer’s diary:

Monday, May 31st, 10 am. hove to, lat. 47° 11', long. 9° 37'. Up to midday engaged in making splice between experimental cable in fore coil and that in main hold, besides other minor operations. In afternoon getting hawser from Niagara and her portion of cable to make joint and splice. 4 pm commenced splice; 5.15, splice completed; 5.25, let go splice frame (weight 3 cwt.) over gangway, amidships, starboard side. 5.30, after getting splice frame* (containing the splice) clear of the ship and lowering it to the bottom, each vessel (then about a quarter of a mile apart) commenced paying‑out in opposite directions.

* This splice frame was used to neutralise the untwisting tendency of two opposite lays when spliced together.

9 pm. got on board Niagara’s warp and her end of cable to make another splice for 2nd experiment.

June 1st 1 am. (night), electrical continuity gone, the cable having parted after two miles in all had been paid out.’

Since 1 am engaged in hauling in our cable. Recovered all our portion, and even managed to heave up the splice frame (in perfect condition), besides 100 fathoms of Niagara’s cable, which she had parted. Fastened splice to stern of vessel and ceased operations.

9.23 am. 2nd experiment. Started paying‑out again. Weather very misty.

9.40, one mile paid out at strain 16 cwt; angle of cable 16o with the horizon: running out straight; rate of ship 2, cable 3.

9.45, changed to lower hold. 9.56, two miles out; last mile in 16½ minutes; strain 17 to 20 cwt; angle of cable 20o. 10.10 am last three miles out in 14 minutes.

10.32 am. four and a half miles out. 3rd experiment. Stopped ship, lowered guard, stoppered cable.

10.50, buoy let go, strain 16 cwt. when let go, the cable being nearly up and down.

11.6, running at rate of 5½ knots paying out, strain 21 to 23 cwt varying. Cable shortly afterwards parted through getting jammed in the machinery.

Other trials included buoying the cable, picking up and then passing the cable from stern to bows. During laying experiments a speed of 7 knots was achieved. On completion of the trials the ships returned to Plymouth.

On the 10th June 1858, a Thursday, a week after reaching Plymouth, the ships set out to rendezvous mid-ocean at co-ordinates latitude 53° 17'; longitude 33° 18'. On the day they left Plymouth the sea was calm, as it was the following day. On the 12th the wind started to pick up and on board Agamemnon the screws were lifted out of the water and the fires raked out and under “royals and studding sails” she sped along. The weather continued to get worse and by Sunday the 20th a full storm was blowing.

THE STORM - June 20th, 1858

As reported at the time:

The Niagara, which had hitherto kept close whilst the other smaller vessels had dropped out of sight, began to give us a very wide berth, and, as darkness increased, it was a case of every one for themselves.

|

Our ship, the Agamemnon, rolling many degrees, was labouring so heavily that she looked like breaking up. The massive beams under her upper deck coil cracked and snapped with a noise resembling that of small artillery, almost drowning the hideous roar of the wind as it moaned and howled through the rigging. Those in the improvised cabins on the main deck had little sleep that night, for the upper deck planks above them were “working themselves free,” as sailors say; and, beyond a doubt, they were infinitely more free than easy, for they groaned under the pressure of the coil, and availed themselves of the opportunity to let in a little light, with a good deal of water, at every roll. The sea, too, kept striking with dull heavy violence against the vessel’s bows, forcing its way through hawse holes and ill closed ports with a heavy slush; and thence, hissing and winding aft, it roused the occupants of the cabins aforesaid to a knowledge that their floors were under water, and that the flotsam and jetsam noises they heard beneath were only caused by their outfit for the voyage taking a cruise of its own in some five or six inches of dirty bilge. Such was Sunday night, and such was a fair average of all the nights throughout the week, varying only from bad to worse. On Monday things became desperate.

The barometer was lower, and, as a matter of course, the wind and sea were infinitely higher than the day before. It was singular, but at 12 o’clock the sun pierced through the pall of clouds, and shone brilliantly for half an hour, and during that brief time it blew as it has not often blown before. So fierce was this gust, that its roar drowned every other sound, and it was almost impossible to give the watch the necessary orders for taking in the close reefed foresail. This gust passed, and the usual gale set in now blowing steadily from the south west, and taking us more and more out of our course each minute. Every hour the storm got worse, till towards five in the afternoon when it raged with such a violence of wind and sea that matters, really looked “desperate” even for such a strong and large ship as the Agamemnon. The upper deck coil had strained her decks throughout; and, though this mass, in theory, was supposed to prevent her rolling so quickly and heavily as she would have done without it, yet still she heeled over to such an alarming extent that fears of the coil itself shifting again occupied every mind, and it was accordingly strengthened with additional shores bolted down to the deck. The space occupied by the main coil below had deprived the Agamemnon of several of her coal bunkers; and in order to make up for this deficiency, as well as to endeavour to counterbalance the immense mass which weighed her down by the head, a large quantity of coals had been stowed on the deck aft. On each side of her main deck were thirty five tons, secured in a mass, while on the lower deck ninety tons were stowed away in the same manner. The precautions taken to secure these huge masses also required attention as the great ship surged from side to side. Everything, therefore, was made “snug,” as sailors call it; though their efforts by no means resulted in the comfort which might have been expected from the term. The night passed over without any mischance beyond the smashing of all things incautiously left loose and capable of rolling, and one or two attempts which the Agamemnon made in the middle watch to turn bottom upwards. In other matters it was the mere ditto of Sunday night; except, perhaps, a little worse, and certainly much more wet below.

Tuesday, the gale continued with unabated force; though the barometer had risen 29.30, and there was sufficient sun to take a clear observation, which showed our distance from the rendezvous to be 563 miles. During this afternoon the Niagara joined company, and, the wind going more ahead, the Agamemnon, took to violent pitching, plunging steadily into the trough of the sea as if she meant to break her back and lay the Atlantic cable in a heap. This change in her motion strained and taxed every inch of timber near the coils to the very utmost. It was curious to see how they worked and bent as the Agamemnon went at everything she met head first. One time she pitched so heavily as to break one of the main‑beams of the lower deck, which had to be shored with screw‑jacks forthwith. Saturday, June 19th, things looked a little better. The barometer seemed inclined to go up and the sea to go down; and for the first time that morning since the gale began some six days previous the decks could be walked with tolerable comfort and security. But, alas! appearances are as deceitful in the Atlantic as elsewhere; and during a comparative calm that afternoon the glass fell lower, while a thin line of black haze to windward seemed to grow up until it covered the heavens with a sombre darkness, and warned us that the worst was yet to come. There was much heavy rain that evening, and then the wind began not violently, nor in gusts, but with a steadily increasing force. The sea was “ready built to hand,” as sailors say; so at first the storm did little more than urge on the ponderous masses of water with redoubled force, and fill the air with the foam and spray it tore from their rugged crests. By and by, however, it grew more dangerous, and Captain Preedy himself remained on deck throughout the middle watch.

At 4 am, sail was shortened to close reefed fore and main topsails and reefed foresail. This was a long and tedious job, for the wind so roared and howled, and the hiss of the boiling sea was so deafening, that words of command were useless; and the men aloft holding on with all their might to the yards as the ship rolled over and over almost to the water were quite incapable of struggling with the masses of wet canvas, that flapped and plunged as if men, yards and everything were going away together. The ship was almost as wet inside as out and so things wore on till 8 or 9 o’clock, everything getting adrift and being smashed, and every one on board jamming themselves up in corners or holding on to beams to prevent their going adrift likewise. At 10 o’clock the good ship was rolling and labouring fearfully, with the sky getting darker, and both wind and sea increasing every minute. Half an hour later three or four gigantic waves were seen approaching the ship, coming slowly on through the mist, nearer and nearer, rolling on like hills of green water, with a crown of foam that seemed to double their height. The Agamemnon rose heavily to the first, and then went down quickly into the deep trough of the sea, falling over in the act, so as to nearly capsize on the port side. There was a fearful crashing as she lay over this way, for everything broke adrift, whether secured or not, and the uproar and confusion were terrific for a minute; then back she came again on the starboard beam in the same manner only quicker and deeper than before. Again, there was the same noise and crashing, and the officers in the ward room, realising the danger, struggled to their feet and opened the door leading to the main deck. The scene, for an instant, defied description. Amid loud shouts and efforts to save themselves, a confused mass of sailors, boys, and marines with deck buckets, ropes, ladders, and every, thing that could get loose, and which had fallen back to the port side were being hurled again in a mass across the ship to starboard. Dimly, and for a moment, could this be seen; and then, with a tremendous crash, as the ship fell over still deeper, the coals stowed on the main deck broke loose, and, smashing everything before them, went over among the rest to leeward. The coal dust hid everything on the main deck in an instant; but the crashing could still be heard going on in all directions, as the lumps and sacks of coal, with stanchions, ladders, and mess tins, went leaping about the decks, pouring down the hatchways, and crashing through the glass skylights into the engine room below.

Breaking Adrift of the Coal on Board HMS Agamemnon

Painting by Henry Clifford

Atlantic-Cable.com Collection

Reproduced in Bright biography, 1898. v.1 p.250

|

Matters now became most serious; for it was evident that two or three such lurches and the masts would go like reeds, while half crew might be maimed or killed below. Captain Preedy was already on the poop, with Lieutenant Gibson, and it was “Hands, wear ship” at once; while Mr. Brown, the indefatigable chief engineer was ordered to get up steam immediately. The crew gained the deck with difficulty, and not till after a lapse of some minutes; for all the ladders had been broken away, the men were grimed with coal dust, and many bore still more serious marks upon their faces of how they had been knocked about below. There was great confusion at first, for the storm was fearful. The officers were quite inaudible; and a wild, dangerous, sea running mountains high, heeled the great ship backwards and forwards, so that the crew were unable to keep their feet for an instant, and in some cases were thrown right across the decks. Two marines went with a rush head foremost into the paying out machine, as if they meant to butt it over the side yet, strange to say, neither the men nor the machine suffered. What made matters worse, the ship’s barge, though lashed down to the deck had partly broken loose; and dropping from side to side as the vessel lurched, it threatened to crush any who ventured to pass. The regular discipline of the ship, however, soon prevailed and the crew set to work to wear round the ship on the starboard tack, while Lieutenants Robinson and Murray went below to see after those who had been hurt. The marine sentry outside the ward room door on the main deck had not had time to escape, and was completely buried under the coals. Some time elapsed before he could be got out; for one of the beams had crushed his arm very badly, still lay across the mangled limb jamming it in such a manner that it was found impossible to remove it without risking the man’s life. The timber indeed, to be sawn away before the poor fellow could be extricated. Another marine on the lower deck endeavoured to himself by catching hold of what seemed like a ledge in the planks but, unfortunately, it was only caused by the beams straining apart, and, of course, as the Agamemnon righted they closed again and crushed his lingers flat. One of the assistant engineers was also buried among the coals on the lower deck, and sustained some severe internal injuries. The lurch of the ship was calculated at forty five degrees each way four or five times in rapid succession. The galley coppers were only half filled with soup; nevertheless, it nearly all poured out, and scalded some of those who were extended on the decks, holding on to anything in reach. These with a dislocation, were the chief casualties; but there were others of bruises and contusions, more or less severe, and a long list of escapes more marvellous than any injury. One poor fellow went head first from the main deck into the hold without being hurt; and one on the orlop deck was “chevied” about for some ten minutes by three large casks of oil which had got adrift, and any one of which would have flattened him like a pancake had it overtaken him.

As soon as the Agamemnon had gone round on the other tack the Niagara wore also, and bore down as if to render assistance. She had witnessed our danger, and, as we afterwards learnt, imagined that the upper deck coil had broken loose and that we were sinking. Things, however, were not so bad as that, though they were bad enough, Heaven knows, for everything seemed to have gone wrong that day. The upper deck coil had strained the ship to the very utmost, yet still held on fast. But not so the coil in the main hold. This had begun to get adrift, and the top kept working and shifting over from side to side, as the ship lurched, until some forty or fifty miles were in a hopeless state of tangle, resembling nothing so much as a cargo of live eels.

Going round upon the starboard tack had eased the ship to a certain extent. The crew, who had been at work since nearly four in the morning, were set to clear up the decks from the masses of coal that covered them. About six in the evening it was thought better to wear ship once more and stand by for the rendezvous under easy steam. Her head accordingly was put about and once more faced the storm. As she went round, she of course fell into the trough of the sea again, rolling so awfully as to break her waste steam pipe, filling her engine room with steam, and depriving her of the services of one boiler when it was sorely needed. The sun set upon as wild and wicked a night as ever taxed the courage and coolness of a sailor. There were, of course, men on board who were familiar with gales and storms in all parts of the world; and there were some who had witnessed the tremendous hurricane which swept the Black Sea on the memorable November 14th, when scores of vessels were lost and seamen perished by the thousand. But of all on board none had ever seen a fiercer or more dangerous sea than raged throughout that night and the following morning, tossing the good ship from side to side like a mere plaything among the waters. The night was thick and very dark, the low black clouds almost hemming vessel in; now and then a, fiercer blast than usual drove the great masses slowly aside, and showed the moon, a dim, greasy blotch upon the sky, with the ocean, white as driven snow, seething like a cauldron. But these were only glimpses, alternated with darkness, through which the waves rushed upon the ship as though they must overwhelm it, and dealing it one staggering blow, went hissing and surging past into the darkness again. The grandeur of the scene was almost lost in its dangers and terrors, for of all the many forms in which death approaches man there is none so easy in fact, so terrific in appearance, as death by shipwreck.

Sleep was impossible that night on board the Agamemnon. Even those in cots were thrown out, from their striking against the vessel’s side as she pitched. The berths of wood fixed athwart ships in the cabins on the main deck had worked to pieces. Chairs and tables were broken, chests of drawers capsized, and a little surf was running over the floors of the cabins themselves, pouring miniature seas into portmanteaus, and breaking over carpetbags of clean linen. Fast as it flowed off by the scuppers it came in faster by the hawse holes and ports, while the beams and knees strained with a doleful noise, as though it was impossible they could hold together much longer. It was, indeed, as anxious a night as ever was passed on board any line of battle ship in Her Majesty’s service. Captain Preedy never left the poop throughout though it was hard work to remain there, even holding on to the poop rail with both hands. Morning brought no change. The storm was as fierce as ever; and whilst the sea could not be higher or wilder, the additional amount of broken water made it still more dangerous to the ship. Very dimly, and only now and then, through the thick scud, the Niagara could be seen one moment on a monstrous hill of water and the next quite lost to

view, as the Agamemnon went down between the waves. Even these glimpses showed us that our Transatlantic consort was plunging heavily, shipping seas, and evidently having a bad time of it. But she got through it better than the Agamemnon, as of course she could. Suddenly it came on darker and thicker, and we lost sight of her in the thick spray, and had only ourselves to look after. This was quite enough, for every minute made matters worse, and the aspect of affairs began to excite serious misgivings in the minds of those in charge. The Agamemnon is one of the finest line of battle ships in the whole navy but in such a storm, and so heavily overladen, what could she do but make bad weather worse, and strain and labour and fall into the trough of the sea, as if she were going down head foremost?

Three or four hours more, and the vessel had borne all she could bear with safety. The masts were rapidly getting worse, the deck coil worked more and more with each tremendous plunge; and, even if both these held, it was evident that the ship itself would soon strain to pieces if the present weather continued. The sea, forcing its way through ports and hawse holes, had accumulated on the lower deck to such an extent that it floated the stoke hole, so that the men could scarcely remain at their posts. Everything was smashing and rolling about. One plunge put all the electrical instruments hors de combat at a blow, and staved some barrels of strong solution of sulphate of copper, which went cruising about, turning all it touched to a light pea green. By and by we began to ship seas. Water came down the ventilators near the funnel into the engine room. Then a tremendous sea struck us forward, drenching those on deck, and leaving them up to their knees in water, and the least versed on board could see that things were fast going to the bad unless a change took place in the weather or the condition of the ship. Of the first there seemed little chance. It certainly showed no disposition to clear on the contrary, livid looking black clouds seemed to be closing round the vessel faster than ever. For the relief of the ship, three courses were open to Captain Preedy one to wear round and try her on the starboard tack, as he had been compelled to do the day before; another, to fairly run for it before the wind; and, the third and last, to endeavour to lighten the vessel by getting some of the cable overboard. Of course the latter would not have been thought of till the first two had been tried and failed in fact, not till it was evident nothing else could save the ship. Against wearing round there was the danger of her again falling off into the trough of the sea, losing her masts, shifting the upper deck coil, and so finding her way to the bottom in ten minutes; while to attempt running before the storm with such a sea on was to risk her stern being stove in and a hundred tons of water added to her burden with each wave that came up afterwards, till the poor Agamemnon went under them all for ever.

Preedy Window

Memorial window to Vice-Admiral Preedy, in All Saints Church, East Budleigh, Devon. The text reads: “In memory of Vice-Admiral George William Preedy CB who when Captain of HMS Agamemnon with the Captain of the USS Niagara successfully laid the first Atlantic Cable uniting Europe and America in 1858.”

Window images courtesy of

Michael Downes,

Budleigh & Brewster

United blog

[archive copy] |

A little after ten o’clock on Monday the 21st the aspect of affairs was so alarming that Captain Preedy resolved at all risks to try wearing the ship round on the other tack. It was hard enough to make the words of command audible, but to execute them seemed almost impossible. The ship’s head went round enough to leave her broadside on to the seas, and then for a time it seemed as if nothing could be done. All the rolls which she had ever given on the previous day seemed mere trifles compared with her performances then. Of more than 200 men on deck at least 150 were thrown down, falling over from side to side in heaps while others, holding on to ropes, swung to and fro with every heave. It really appeared as if the last hour of the stout ship had come, and to this minute it seems miraculous that her masts held on. Each time she fell over her main chains went deep under water. The lower decks were flooded, and those above could hear by the fearful crashing audible amid the hoarse roar of the storm that something alarming had happened. It was then found that the coals had, once more got loose below, had broken into the engine room, and were carrying all before them. During these rolls the main deck coil shifted over to such a degree as to entirely envelope four men, who sitting on the top, were trying to wedge it down with beams. One of them was so much jammed by the mass which came over him that he was seriously confused. He had to be removed to the sick bay, making up the sick list to forty five of which ten were from injuries caused by the rolling of the ship, and most of the rest from continual fatigue and exposure during the gale.

Once round on the starboard tack, and it was seen in an instant that the ship was in no degree relieved by the change. Another heavy sea struck her forward, sweeping clean over the fore part of the vessel, and carrying away the woodwork and platforms which had been placed there round the machinery for under running. This and a few more plunges were quite sufficient to settle the matter; and at last Captain Preedy reluctantly succumbed to a storm he could neither conquer nor contend against. Full steam was got on, and, with a foresail and foretopsail to lift her head, the Agamemnon. ran before the wind, rolling and tumbling over the huge waves at a tremendous pace. It was well for all that the wind gave this much way on her, or her stern would certainly have been stove in. As it was, a wave partly struck her on the starboard quarter, smashing the quarter galley and ward‑room windows on that side; and sending such a sea into the ward room itself as to wash two officers off a sofa. This was a kind of parting blow; for the glass began to rise, and the storm was evidently beginning to moderate; and although the sea still ran as high as ever, there was less broken water, and altogether, towards midday, affairs assumed a better and more cheerful aspect. The ward room that afternoon was a study for an artist; with its windows half darkened and smashed, the sea water still slushing about in odd corners, with everything that was capable of being broken strewn over the floor in pieces, and some fifteen or twenty officers, seated amid the ruins, holding on to the deck or table with one hand, while with the other they contended at a disadvantage with a tough meal, the first which most had eaten for twenty four hours. Little sleep had been indulged in, though much lolloping about. Those, however, who prepared themselves for a night’s rest in their berths rather than at the ocean bottom, had great difficulty in finding their day garments of a morning. The boots especially went astray, and got so hopelessly mixed that the man who could “show up” with both pairs of his own was, indeed, a man to be congratulated.

But all things have an end; and this long gale of over a week’s duration at last blew itself out, and the weary ocean rocked itself to rest. Throughout the whole of Monday the Agamemnon ran before the wind, which moderated so much that at 4 a.m. on Tuesday her head was once more put about; and for the second time she commenced beating up for the rendezvous then some 200 miles further from us than when the storm was at height on Sunday morning. So little was gained against this wind, that Friday, the 25th sixteen days after leaving Plymouth still found us some fifty miles from the rendezvous. It was, therefore, determined to get up steam and run down on it at once. As we approached the place of meeting the angry sea went down. The Valorous hove in sight at noon; in the afternoon the Niagara came in from the north; and at even, the Gorgon from the south and then, almost for the first time since starting, the squadron was reunited near the spot where the great work was to have commenced fifteen days previously as tranquil in the middle of the Atlantic as if in Plymouth Sound.

Once it was established that all was well preparations were made to start laying the cable. Those on board the Agamemnon had the task of recoiling the cable which was stored on deck this taking several days. Finally on Saturday 26th June they were ready.

As reported at the time:‑

The end of the Niagara’s cable was sent on board the Agamemnon, the splice was made, a bent sixpence put in for luck, and at 2.50 Greenwich time it was slowly lowered over the side and disappeared for ever. The weather was cold and foggy, with a stiff breeze and dismal sort of sleet, and as there was no cheering or manifestation of enthusiasm of any kind, the whole ceremony had a most funereal effect, and seemed as solemn as if we were burying a marine, or some other mortuary task of the kind equally cheerful and enlivening. As it turned out, however, it was just as well that no display took place, as everyone would have looked uncommonly silly when the same operation came to be repeated, as it had to be, an hour or so afterwards. It is needless making a long story longer, so I may state at once that when each ship had paid out three miles or so, and they were getting well apart, the cable, which had been allowed to run too slack, broke on board the Niagara, owing to its overriding and getting off the pulley leading onto the machine.

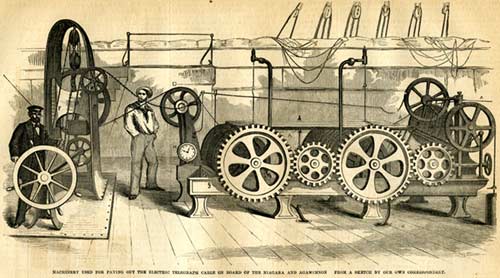

Machinery used for paying out the electric

telegraph

cable on board of the Niagara and Agamemnon.

|

The break was, of course, known instantly, both put about and returned, a fresh splice was made, and again lowered over at half past seven. According to arrangement, 150 fathoms were veered out from each ship, and then all stood away on their course, at first at two miles an hour, and afterwards at four. Everything then well, the machine working beautifully, at thirty two revolutions per minute, the screw at 26, the cable running out easily at five and five and a half miles an hour, the ship going four. The greatest strain upon the dynamometer was 2500 lb , and this was only for a few minutes, the average giving only 2000 lb, and 2100 lb. At midnight twenty‑one nautical miles had been paid out, and the angle of the cable with the horizon had been reduced considerably. At about half past three forty miles had gone, and nothing could be more perfect and regular than the working of everything, when suddenly, at 3.40 am on Sunday, the 27th, Professor Thomson came on deck and reported a total break of continuity; that the cable, in fact, had parted, and, as was believed at the time, from the Niagara. The Agamemnon was instantly stopped and the brakes applied to the machinery, in order that the cable paid out might be severed from the mass in the hold, and so enable Professor Thomson to discover by electrical tests at what distance from the ship the fracture had taken place. Unfortunately, however, there was a strong breeze on at the time, with rather a heavy swell, which told severely upon the cable, and before any means could be taken to ease entirely the motion on the ship, it parted a few fathoms below the stern wheel, the dynamometer indicating a strain of nearly 4000 lb. In another instant a gun and a blue light warned the Valorous of what had happened, and roused all on board the Agamemnon to a knowledge that the machinery was silent, and that the first part of the Atlantic cable had been laid and effectually lost.

The great length of cable on board both ships allowed a large margin for such mishaps as these, and the arrangement made before leaving England was that the splice might be renewed and the work recommenced till ship had lost 250 miles of wire, after which they were to discontinue their efforts and return to Queenstown. Accordingly, after the breakage on Sunday morning, the ships’ heads were put about, and for the fourth time the Agamemnon again began the weary work of beating up against the wind for that everlasting rendezvous which we seemed destined to be always seeking. Apart from the regret with which all regarded the loss of the cable, there were other reasons for not wishing the cruise to be thus indefinitely prolonged, since there had been a break in the continuity of the fresh provisions; and for some days previously in the ward‑room the pièces de resistance had been inflammatory-looking morceaux, salted to an astonishing pitch, and otherwise uneatable, for it was beef which had been kept three years beyond its warranty for soundness, and to which all were then reduced.