|

|

Amazon Telegraph Company’s Cable

Para Manaos

Contractors

Hooper’s Tel. & I.R. Works

Cable samples courtesy of Jim

Kreuzer |

1600 nm in length, this cable was laid by Siemens Bros. for the Amazon

Telegraph Company using CS Faraday (1), and opened for traffic in February 1896.

The sample case above is somewhat of a mystery; the plate on the case gives as contractors "Hooper’s Tel. & I.R. Works", the corporate name adopted by Hooper’s in 1894, but all the records of this cable show that it was made and laid by Siemens Brothers. The Amazon Telegraph Company was an offshoot of the Western and Brazilian Telegraph Company, most of whose cables had been made by Hooper’s. While each sample above is clearly marked "Hooper’s", the style of the mounts is characteristic of Siemens. as can be seen from the sample below.

This cable sample is marked "Amazon River Cable" and "Siemens Brothers"; it is not the same as any of the samples in the Hooper’s case:

|

|

|

Amazon River Cable

Siemens Brothers London

Cable sample images courtesy of Gustavo Coll |

On 3 December 1895, news of the start of the cable expedition was reported in a number of newspapers:

AMAZON RIVER CABLE

The Faraday Will Shortly Leave England with the Outfit on Board.

WASHINGTON, Dec. 3.-Brazil advices state that the British steamer Faraday will shortly leave England with the the cable which is to be laid in the Amazon river from Para to Manaos. This enterprise is being carried out by an English company under an exclusive contract with the Brazilian government. The line will be 1,400 miles long and will have sixteen intermediate stations. All previous attempts at establishing telegraphic communication in these districts have been unsuccessful, owing to the dense and rapid growth of the forest along the banks of the river.

Site visitor James Catmur’s great-grand uncle, Herbert Johnson, was a member of the cable staff on board CS Faraday, and the photographs below have come down in the family from him. Herbert would have been aged 18 at the time of the expedition.

James Catmur adds this biographical information:

Herbert Braithwaite Johnson was born on 16 August 1877, in Brocklesbury, Lincolnshire, England, to John Henry Johnson B.A. and Anna Braithwaite Johnson [Savory]. He was recorded in the census in 1881, aged about 3, in Station Lane, Kirmington, Kirmington, Lincolnshire, England. He was recorded in the census in 1891, aged about 13, in Thirmongton, Kirmington, Lincolnshire, England. Herbert died on 6 September 1960, aged 83 years, in Jalisco, Mexico. Herbert was buried in 1960 in Ajijic, Mexico.

There is more information on Herbert Johnson, who with his wife Georgette settled in Ajijic, Mexico in 1939, at the Lake Chapala Artists website.

All images in this section are courtesy of and copyright © 2022 James Catmur.

Herbert Johnson

|

CS Faraday crew and cable staff

|

CS Faraday Captain and cable staff

|

Original photo marked “Siemens family member.”

The only known family member to sail on this expedition was Alexander Siemens,

so although we cannot be certain, if the photo caption is correct then this is him.

|

|

Landing the cable via a trench on the shore,, location unknown

|

Cable staff on the shore with equipment cart |

The Faraday encountered

many problems while laying the cable, on one occasion being stranded on a sandbar

for nine days. The project was reported as completed on 13 February 1896:

New York, Feb. 13. --The Anglo-American Telegraph Company is advised that cables have been laid in the Amazon River between Para and Manaos in Brazil. The office at Manaos is open for traffic.

Maintaining the cable was also a problem: in the rainy season a large amount of debris was carried down the Amazon River, and strong currents scoured the river bottom and uncovered the cable, causing frequent faults. CS Viking (1) was transferred from the Western and Brazilian and converted for repair

work under the Amazon conditions. This ship was scrapped in 1901, and CS Viking (2) then took over, joined in

1912 by CS Ramos.

CABLE-LAYING ON THE AMAZON RIVER.

By Alexander Siemens, M.I.C.E., M.I.E.E.

Paper read before the Royal Institution, Friday May 15th 1896.

Published in The Electrical Engineer, 29 May 1896.

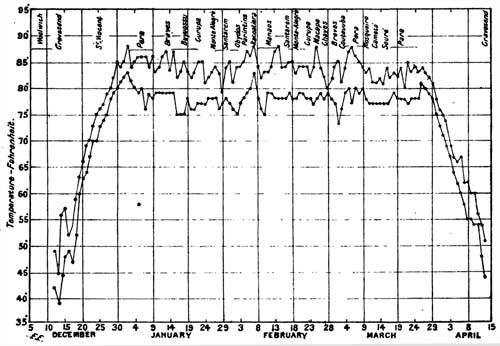

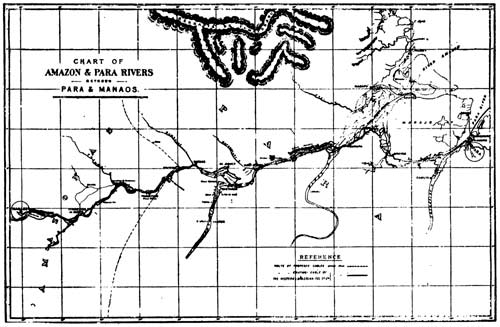

When it had been decided to connect Belem, the capital of the State of Para, by means of a subfluvial cable with Manaos, the capital of the State of Amazonas, a preliminary journey became necessary, during which landing places at the various intermediate stations had to be selected. As no reliable charts exist, some reaches of the river had to be explored, and various other details ascertained in order to facilitate the laying of the cable. This preliminary survey took place in October of last year [1895] during the hottest season, when the river was at its lowest, while the cable was laid during January and February of this year [1896], when the rainy season had commenced and the river was rising. The difference in temperature between the two journeys was on the average not more than about 5½deg. C. (10deg. F.), but a great advantage during the laying was the almost continuous presence of clouds, which mitigated the fierce heat of the sun and kept the temperature at a very pleasant level. The diagram (Fig. 1) shows the curves of the variation in temperature during the cable-laying expedition, and gives the daily maximum and minimum temperature registered by a thermometer hung up under the officers’ bridge in the open air, but sheltered from the sun. The third curve represents the temperature of the water, which was measured by a thermometer on the refrigerating machine fixed at a point where the water pumped in from outside first enters the machine. Besides the date, the places where the observations were taken are marked on the diagram, and it will at once be noticed how very equable the temperature was on the main river. The fluctuations in the air temperature are mostly indicating the absence or presence of clouds, but the water temperature remained perfectly constant during the whole time that the ship spent on the upper reaches of the river. The proximity of the sea lowers the temperature only to a small extent, as is clearly shown by these curves. A glance at the map of South America explains without much comment how immense the volume of water must be which is collected from an area measuring more than 2½ million square miles, for the most part covered with dense forests; and it follows that the temperature of such a body of water cannot be seriously affected by the daily variations of temperature indicated by the first two curves.

Fig.1 Diagram showing the Maximum and Minimum Temperatures observed |

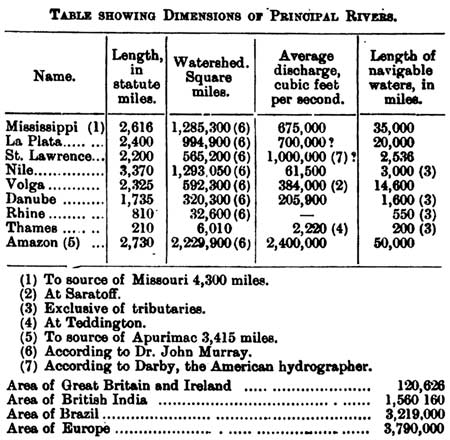

It is extremely difficult to realise the true proportions of this river, but the comparative table, in which the dimensions of the principal rivers of the various continents are contrasted with those of the Amazon, will help to show the importance of this great system of natural waterways. With several other large rivers, the Amazon shares the fate that its name changes several times during its long course, and that at various times different affluents have been considered to be the true source of the main stream. Most geographers, however, regard the Maranon as the principal river, a branch of which, called Tunguragua, rises in Lake Lauricocha, in Peru, in 10deg. 30min. S. lat. and 76deg. 10min. W. long.; although the Ucayale, where it unites with the Maranon at Nauta (4deg. S. lat, 73deg. W. long.), is quite as important as the Maranon. If the greatest distance from the mouth is to decide the question, then the source of the Apurimac, an affluent of the Ucayale, can lay claim to being the origin of the Amazon, rising in Peru in 16deg. S. lat. and 72deg. W. long. From the Lake Lauricocha the main direction of the Tunguragua and the Maranon is to the N.N.W. until the river turns eastward, and shortly after passing Jaen breaks through the Andes, entering the plains of the Amazon valley by the Falls of Manseriche a short distance west of Borja. Its further course is a little north of east until it pours its yellow waters into the Atlantic under the equator between the Cabo do Norte and the Cabo Maguari, which are 158 miles apart. This distance is just about equal to the distance from Lands End to Cape Clear in Ireland, or from Brighton to Falmouth. Even west of the island of Caviana, which lies in the mouth of the river, together with the island of Mexiana and several smaller ones, the width of the main stream is over 50 miles, equal to the distance from Portland Bill to the Cap de la Hague. The part of the Amazon flowing north of the island of Marajo may therefore be compared in width to the Channel, but in depth and volume of water it far surpasses it.

Table showing Dimensions of Principal Rivers |

It is a disputed question whether the water flowing south of Marajo, commonly called the Para River, should be considered as part of the Amazon or not. A network of natural canals, “the narrows,” connects the two waterways west of Marajo, but the influence of the tide makes it difficult to decide whether part of the water of the Amazon finds its way south of Marajo or not. Along the whole course of the Amazon, commencing at the foot of the Andes, a similar network of islands and canals is formed on both sides of the river, as the whole country is almost level, and is consequently inundated during the rainy season for hundreds of miles by the rivers flowing through it. The most notable exception to this general state of things occurs at Obidos, where the whole volume of water is compressed into one channel a little over a mile wide, and said to be about 40 fathoms in average depth. A sounding taken opposite Obidos, about a third of the distance across the river, showed a depth of 58 fathoms, measured by a steel wire and Sir William Thomson’s sounding machine. As the current of the river averages three knots in the main channel, it is not easy to take soundings by an ordinary lead-line, and even with the steel wire an extra heavy weight (33lb.) has to be employed, or the results are not reliable.

Besides the wire sounding machine, a submarine sentinel was used on the preliminary voyage wherever serious doubts existed about a channel through which the cable was to be laid. This apparatus consists of a small winch, from which a wire leads into the water and drags at a short distance behind a piece of wood, shaped like an angle iron, in a nearly upright position. The wire is not attached directly to the piece of wood, but to a string, kite fashion, and the wood is fitted with an iron foot, which, on coming in contact with the bottom of the water, releases one end of the kite string, so that the wood remains attached to the winch wire with one end only. The consequence is that the strain on the wire is suddenly reduced to a very small amount, and the piece of wood appears on the surface of the river. It depends on the quantity of wire paid out how deep the kite or the sentinel floats, and its action is quite reliable, so that it is unnecessary to take soundings by the line or by wire while the sentinel is being dragged by the ship. Usually the sentinel was set at five fathoms, and when it struck a bar the ship was stopped, and a series of soundings taken to ascertain the exact depth of water and the extent of the shallow place.

A further difficulty in sounding originated from the soft nature of the soil, which, for the greater part of the Amazon valley, is alluvial clay, and allows the lead to sink into it for several feet. In the narrows there appears, however, a bank of hard clay, called tabatinga, which unfortunately blocks nearly all the branches of the narrows and creates bars all I along the course of the Tajipuru, the main westerly waterway connecting to the Gurupa branch of the main river. Occasionally the same hard clay forms shallows in the main river, but as a rule the section of all the channels resembles the capital letter U—i.e., the sides are very steep and the bottom flat. In this respect, as in many others, the Amazon differs entirely from the Indian rivers, which build up their beds above the surrounding country, occasionally breaking through their natural banks and seeking a new bed. The Amazon, on the other hand, carries with it only the light clay sediment which forms the soil of the whole valley, and the inducement for the main stream to alter its course is therefore very small, and long straight reaches are the result.

|

Under these circumstances the largest vessels can ascend the river nearly to the foot of the Andes, but the constantly changing sandbanks at the mouth of the Amazon proper make this approach of the river dangerous, and the State of Para is, for obvious reasons, not over-anxious to have the deep channels properly buoyed and surveyed. This forces all the shipping to enter the Para River and to pass the narrows if the Amazon is the goal of the journey. In doing the latter, the choice for large ships lies between one of the channels (called furos) with a bar where it joins the Tajipuru and a furo, the Macajubim, which has plenty of water, but which winds about in such a serpentine fashion that only ships with twin screws can pass it unassisted. These difficulties are, however, much diminished during the rainy season, when the river rises to such an extent as to drive all the inhabitants of its banks into the towns which have been built wherever a natural eminence secured the inhabitants against the Hood. Near the mouth the difference is naturally not so great as higher up, where the influence of the tide is felt less, but at Manaos the difference in level between low river and high river exceeds 40ft.

With all rivers carrying sediment, the Amazon shares the peculiarity that its immediate banks are higher than the country lying behind them, and thus we have in the rainy season the spectacle of the main river flowing between two banks covered with dense forest and immense lakes stretching out on either side of these banks. These do not entirely dry up during the remainder of the year, so that the whole of the Amazon valley really forms a huge swamp covered with a most luxuriant forest, which below Manaos narrows to a broad belt close to the main river with prairies, called campos, at the back of the forest stretching out to the hills, where the forest recommences. In such a country no land communication of any sort can be attempted, as the tropical vegetation and the annual inundations of the rivers destroy everything that man places in the way of the natural forces. By water, on the other hand, the intercourse between all habitable parts of the country is easy and expeditious since steamers have been introduced in the year 1853. At that time the journey from Belem to Manaos was shortened from 40 days to eight days, and at present the ocean-going steamers, which do not call at the intermediate places, accomplish the distance in three days.

Belem, the capital of the State of Para, lies on a branch of the Para River, called Guajara, which unfortunately does not share the characteristic shape of the Amazon and the furos, but forms a rather shallow basin in front of the town. The general aspect of the town, but for the presence of palm trees, does not differ much from that of a European seaport. Even the clothing of a good many inhabitants seems better adapted to a colder climate ; it is only the airy costume of the ladies, and still more the absence of any costume on the children, that betrays the tropical climate. The harbour of Para is very full of shipping, and the general build of the steamers is well adapted to navigate the broad waterway of the main river as well as the smaller and shallower affluents, which become more and more inhabited from year to year. As the cable steamer could not approach close enough to Para, the shore ends were laid with the help of a barge and a tug without anything occurring that need be mentioned. By the same means the sections from Para to Pinheiro, and from there to Mosqueiro, were laid, the large steamer laying, the section to Soure across the Para River. These three places are much resorted to by the inhabitants of Para for their healthy situation, and because they imagine that salt water reaches at least Soure. The views show how the forest encircles all the houses, but the proximity of the sea and the breeze blowing regularly every afternoon make all these places extremely comfortable. At Soure the ss. “Faraday” was anchored at a convenient distance from the shore, so that the shore end might be landed direct from the ship, and as long as the tide was rising this plan appeared excellent. By the receding tide, however, a whirlpool was formed with the ship lying right across the centre, and when it had been turned 17 times in one hour the captain was tired of it and moved the ship to a safer anchorage. Another branch of the cable was laid from Para to Cameta, on the River Tocantins, which is 1,200 miles long, but unfortunately has some rapids not far from Cameta, which cut off the navigable upper portion of the river from direct communication with the general Amazon system. Cameta boasts of a fine old church and a number of two-storeyed buildings, indicating the prosperous state of the township.

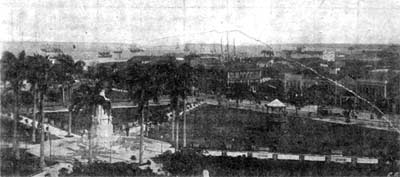

The Harbour at Para, taken from

the roof of the Governor’s Palace |

The first station on the main cable is Breves, the centre of the rubber trade of the islands of the lower Amazon, situate in the centre of “the narrows.” Between Para and Breves there is only one shallow passage, near the lighthouse of Gujabal, and the pilot managed to run the ship aground there. Luckily it was low tide, and with the rising tide the ship could be turned. At Breves the ship was anchored close to the shore, and its stern secured to a tree by a rope so that the tide could not cause it to Under these circumstances the landing of the shore ends was an easy matter and soon finished. The ship then resumed its way into the narrow furos described above, and the night did not put a stop to its progress, as the outlines of the forest were clearly visible against the sky and the waters everywhere more than seven fathoms deep. While the speed of the ship was kept at about six knots, the pilot ordered the quartermaster to put the helm astarboard, as he wished to increase the distance between ship and shore. The quartermaster was, however, confused, and put the helm hard-a-port, with the result that the bows went into the forest until the branches of the trees touched the foreyard. To appreciate the situation, it should be mentioned that the foremast stands 74ft. abaft the bows, and that the foreyard is 69ft. above the water level. Luckily, the soft ground, the elasticity of the forest trees, and the steepness of the banks rendered this accident quite harmless, and on reversing the engines the ship at once came off, so that the laying could be resumed.

Not far from this spot the Aturia furo branches off, through which the cable had to be laid, but which was impassable for the ss. “Faraday” on account of a two-fathom bar at the Tajipuru end of the furo. As a splice had to be made with some cable on a barge from which it was to be paid out through the Aturia furo, the “Faraday” had to be anchored, and the right-hand shore was approached so as to leave room for the ship to swing round when the tide turned. At the critical moment when the anchor was to be lowered, somebody blundered, and turned the electric light out, leaving the anchor winch and its surroundings in darkness. By the time this mistake had been rectified the ship was dangerously near the shore, and even the anchor could not sufficiently check its advance, so that it ran again ashore, stopping within about 5ft. of a house, much to the alarm of the inhabitants. This manoeuvre fixed the ship in a most convenient position, so that it was left there until the splice had been finished and the tug “Cochrane,” with the barge, had started laying the cable in the Aturia furo. Again there was no difficulty in backing the ship off the bank, but the furo proved to be too narrow to turn the ship, which had to return to Breves, or rather a few miles beyond to the mouth of the Boiuassu, in order to enter the furo grande and the Tajipuru in a roundabout way. As the ship was drawing over 24ft, and the bar at the end of the Boiuassu had only 23ft. of water at high tide, the result was easily foreseen, but the ship remained on the bar for nine days, by which time sufficient cable had been transferred to the barge and to the ss. “Malvern” to enable the ship to continue her journey. During this enforced sojourn in the midst of the most wonderful combination of islands and rivers, the two naturalists which the British Museum authorities had kindly sent with the expedition took full advantage of the opportunity to explore the locality in all directions.

Unfortunately, the time is too short to give many details of the intermediate stations, but their general aspect is very similar, and nothing noteworthy occurred at most of them. Commencing at the mouth of the river, the first station is Chaves, and the second Macapa; to these two places a branch is laid from Gurupa. The ss. “Faraday” had the distinction of being the first European steamer which has navigated the Amazon river below the mouth of the Tajipuru; in fact, neither the pilots nor the inhabitants knew of any foreign ship that had ever touched at these ports. In Gurupa, the second station of the main line, the inhabitants expressed their joy at being put in communication with the rest of the world by actively helping in the landing of the first shore end. A young lady in white, niece of the Mayor, borrowed a handkerchief from one of our engineers, daintily laid hold of the end of the cable, and triumphantly carried it into the station. Here a ball was started, and the happy couples waltzed round the cable-end to show their appreciation. Meantime, the tug began pulling on the barge from which the cable was to be paid out, and just as these vessels began to feel the current, which runs rather strong there, something jambed, the cable would not run out, and the tug could not hold the barge against the current. Barge, tug, and cable drifted down stream, the end gradually disappearing out of the station. This contretemps luckily did not disturb the dancers, who continued their rejoicings until the end had been brought back.

Monte Alegre lies on a furo which, unfortunately, has a shallow bar at its mouth, so that the cable had to be laid in and out by the barge and tug. This furo is swarmed with “botos,” a species of dolphin much coveted by the naturalists, but the natives do not try to catch them because they are neither good for food nor useful in other ways ; besides they are remarkably shy and strong. From there the cable is laid to Santarem, at the mouth of the Tapajos, which presents a strong contrast to the Amazon on account of its clear waters and tranquil flow. This river is 1,200 miles long, and is formed by the union of the Arinos and Juruena, rising 14deg. 42min. S. lat. and 60deg. 43min. W. long., in the so-called aguas vertentes (the turning waters) close to the sources of some of the affluents of the Paraguay River. In the rainy season all these waters mix, and it is possible to pass in a boat from the mouth of the Rio de la Plata in 35deg. S. lat. to the mouth of the Orinoco in 10deg. N. lat. by way of the Paraguay, the Tapajos, the Amazon, the Rio Negro, and the Cassequiare, which forms a connecting link between the Amazon system and the Orinoco. From Santarem a branch cable is laid to Alemquer, and Obidos, the next station of the main line, is the last point touched in the State of Para.

Typical Riverside View on the Amazon |

It would not be right to leave unnoticed the rubbergathering industry, which is at once the wealth and the bane of this part of the world. The implements in use are of the most primitive kind, as may be judged by the samples on the table, but the average earnings can easily be £3 per day during the dry season, and the facility of earning so much money with little exertion makes the inhabitants unwilling to engage in more arduous labour. A narrow path leads from the hut on the water’s edge into the forest from one rubber tree to another, the path eventually returning to the hut. The trees are cut on the morning round, and the rubber is gathered in the afternoon. As soon as it arrives at the hut a fire of oily palm nuts (Attalca excelsa) is lighted, and the thin sap thickened in the smoke. For this purpose a paddle is used on to which the sap is poured with a small earthenware or tin vessel. The smoke soon thickens it, and a new layer is poured on until the well-known flat cakes of indiarubber have been formed. Owing to the rise of the river during the rainy season most of the huts have to be abandoned, and it can easily be imagined how comfortless they are. Nearly all of them are built on piles, and most of them are thatched with palm leaves. There is hardly any attempt made to cultivate the soil, such as it is, but everything is imported. The “Cametense,” in which the surveying party went out, was laden with cabbages, onions, and potatoes, part of which went as far as Iquitos, in Peru. Chiefly owing to this want of provisions and to the generally careless mode of life, the mortality among indiarubber-gatherers is very great.

There are two stations in the State of Amazonas—Parentins, formerly called Villa Bella da Imperatriz, and Itacoatiara, formerly Serpa. Just before reaching the former station the Serra de Parentins is passed, which forms the boundary between the two states. At Parentins the river makes a sudden bend, and the resulting eddy-current greatly impeded the work ; at Itacoatiara, on the other hand, the bow of the ship was run ashore and the end of the cable landed direct from the ship.

No words can describe the luxuriance of the vegetation met with everywhere on the journey better than has been done to perfection in the classical works of Bates and Wallace. Everything they have said in this respect remains as true as it was 40 years ago, and hardly anything new can be added to their description of the general features of the Amazon valley, but the town of Manaos has completely changed its character since it was made the capital of that region in 1853. A town quite European in its features has arisen in the midst of the forests, and to the benefits of rapid transport, to which it has owed so much, there is now added the characteristic lever of modern progress, the annihilator of space and time—electrical communication.

|